WITH the world's largest biometric ID database, a pioneering digital payment system for daily transactions and a flagship space and satellite programme, India knows the power of connected technology.

But when trouble brews with political unrest or sectarian violence, authorities are quick to sever Internet service to stem disinformation — cutting off millions of people who depend on the web for communication, information and business.

For authorities, Internet shutdowns have "become the first tool in their toolkit", said Indian online civil liberties activist Mishi Choudhary. Some blackouts last hours, others days. Some stretch for months.

In India's northeast Manipur state, more than three million people have been cut off from mobile Internet since clashes broke out in May. That meant it took two months for Phijam Ibungobi to find out that his missing 20-year-old son had been one of the more than 150 people killed in the violence.

When the Internet was briefly restored in September, photographs of the young man's corpse circulated on social media.

"The Internet meant I could find out the news of my son — even if that news was tragic," Ibungobi told AFP in tears.

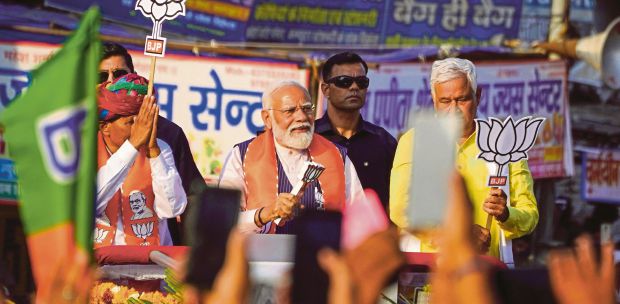

India, the world's largest democracy, with a general election due next year, is also a global leader in Internet shutdowns, according to New York-based online freedom monitors Access Now.

Of the 187 Internet shutdowns it recorded worldwide last year, 84 were in India, the "most of any country for the fifth consecutive year", it said.

The main reasons India gave for the shutdowns were protests and the need to prevent cheating during exams, according to an analysis of blackouts from 2020 to 2022 by the Internet Freedom Foundation.

The tactic helps the government shape its narrative "as no counter voices emerge", said Choudhary, founder of the Software Freedom Law Centre. But she said the authorities fail to understand "what the impact would be".

Human Rights Watch argues Internet shutdowns "disproportionately hurt" the poorest, who depend on the government's online social support systems.

Nearly 121 million people were affected by shutdowns last year, HRW said in a report in June.

"In the age of 'Digital India', where the government has pushed to make the Internet fundamental to every aspect of life, the authorities instead use Internet shutdowns as a default policing measure," HRW's Jayshree Bajoria said in the report.

In Indian-administered Kashmir, a 500-day blackout from 2019 to 2020 cost the economy more than US$2.4 billion, according to the region's traders.

"Internet access is vital for realising economic security," Access Now said.

From market traders to larger businesses dependent on online apps for payment, the loss of Internet access stifles trade.

"I am living hand to mouth," said Mark Fanai, 42, who was working from home in Manipur for a New Delhi-based law firm when the Internet was cut.

Initially, he spent up to 12 hours a week commuting to the state border to send emails and make online payments, but eventually, he was forced to relocate to neighbouring Mizoram state.

The bans also hinder journalists. When protesters demanding job quotas in Maharashtra state torched the homes of lawmakers last month, authorities turned off the Internet for three days.

"The authorities usually suspend Internet whenever they see some sort of disturbance getting worse," said Vinod Jire, a journalist in Maharashtra's Beed district.

"Work was extremely difficult," said Jire, who had to leave the district to file his story on the incident. "It is our job to report facts and news accurately."

The government says Internet cuts curb disinformation by stemming rumours from spreading on social media or mobile messaging applications.

In August, authorities blocked the Internet in parts of Haryana state — just north of New Delhi — when at least six people were killed in sectarian conflict between Hindus and Muslims, violence exacerbated by posts online.

External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has dismissed the "big song and dance" about Internet cuts.

"If you've reached the stage where you say an Internet cut is more dangerous than the loss of human lives, then what can I say?" Jaishankar said in 2022.

But Internet access advocate Tanmay Singh from the Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation points out: "Your primary defence against misinformation is fact verification and fact checking."

The writers are from Agence France-Presse