"BOOM, boom, boom! The whole mountain shook when the big guns opened up. I could feel my body shaking too," my father recounted, tone laced with trepidation as I sat spellbound listening to his story about the war.

The long-awaited Battle of Kampar had finally begun. It was 1942, on New Year's Eve and rather ominously, the big guns seemed to be welcoming the new year with a sinister premonition.

Indeed, what followed turned out to be one of the most traumatic experiences for both Malaya and Malayans. The Battle of Kampar was the most ferocious battle on home soil during World War 2, with thousands dead and many more injured. I recall my father telling me that the battle was fiercest at the summit where my grandfather was buried.

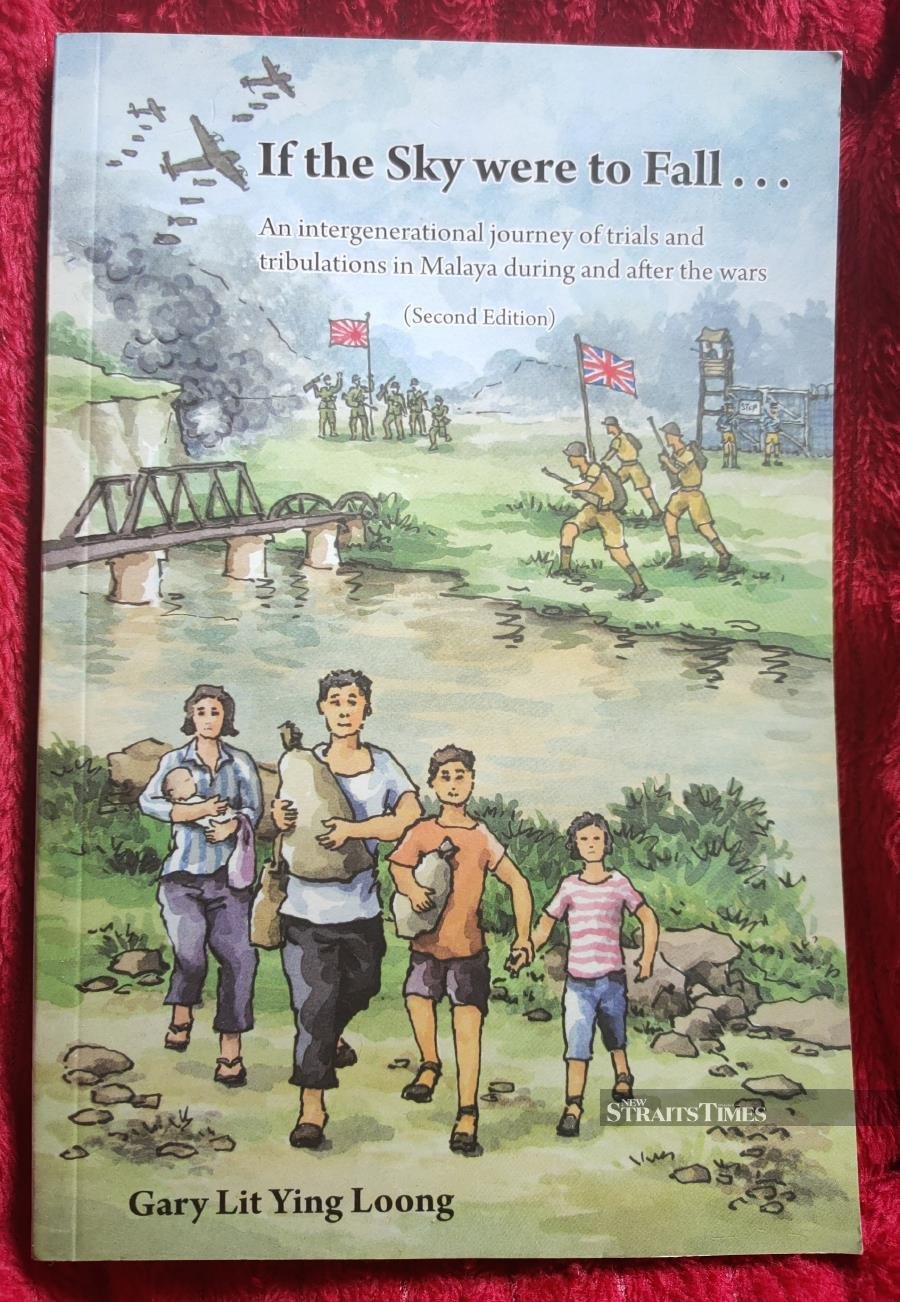

During a recent visit to Kampar Hill to mark the launch of my latest book, If The Sky Were To Fall, I decided to take the opportunity to elaborate further about the various events that I'd described in my book, to my group of friends who'd joined me on this nostalgic tour.

Standing silently with them on the hill's windswept slope, I couldn't help but recall my father's stories…

REMAINS OF WAR

I could almost hear the loud battle cries of "Banzai!" as the Japanese army, having overrun Thomson and Green Ridge, charged up the steep hills towards the summit where the Chinese cemetery was located. Until today, some British ammunition boxes and the remains of Japanese aircrafts may still be found at the site.

Curiosity aroused, someone in the group asks why the British chose to fight the battle on Kampar Hill? I smile knowingly before leading everyone's gaze to the horizon and urging them to admire the view of the surrounding Kinta Valley. It's not long before their heads bob in unison as they arrive at the answer. Just like the British, they too could see the advantages of having a strategic commanding view.

Despite the passing years, the war trenches at Kampar Hill can still be seen to this day. Try standing in one and you may just feel the intensity of the battle. I certainly can.

Suddenly drifting back in time, I see in my mind how the tenacious British army mowed down the advancing Japanese with their machine guns and mortar fire from their well-entrenched positions. I can almost hear the desperate cries of the dying and wounded soldiers on that fateful day.

ESCAPE TO THE JUNGLE

To escape the invading Japanese army, my grandpa took the whole family, with 13 children in tow, to hide in a cave deep in the jungle. I still remember my father's words: "After our rice ran out, we had to survive on tapioca every day. Some of us eventually developed ugly sores and sickness. We could hear tigers roaring almost every night!"

Concerned, one of the women in the group asks whether the family was safe in the jungle. I shake my head solemnly before telling her about my baby aunt who fell ill and died of malaria.

Another young aunt had to be given away as my grandpa couldn't feed so many mouths during the war. I recall my father's doleful voice as he recalled: "Losing my beloved sisters was the saddest part of my life."

However, their one-year stay in the harsh jungle made them stronger mentally and physically. They developed an inner resilience and fortitude that stood them in good stead in the ensuing years of hardship and deprivation.

JAPANESE OCCUPATION

The British Far East Headquarters of Singapore fell to the Japanese on Feb 15, 1942 after only about a week of fighting. The then British prime minister Winston Churchill had described the British surrender in Singapore as the worst military capitulation in the history of the British Empire.

"How could the British surrender to the Japanese? They had a much bigger army and bigger guns too," someone in the group blurts out. Well, the big British guns of Labrador and Sentosa were caught pointing the wrong way as Yamashita's army attacked Singapore from the north via Johor Baru. This was an instructive and imperative lesson for all military colleges around the world today.

After the fall of Singapore, the Japanese Occupation lasted a total of three years and eight months. My father described it as "living hell" on earth. Countless millions of innocent Malayan folks were subjected to terrible atrocities and brutalities. There were torture, murders and gang rapes by the Japanese almost daily.

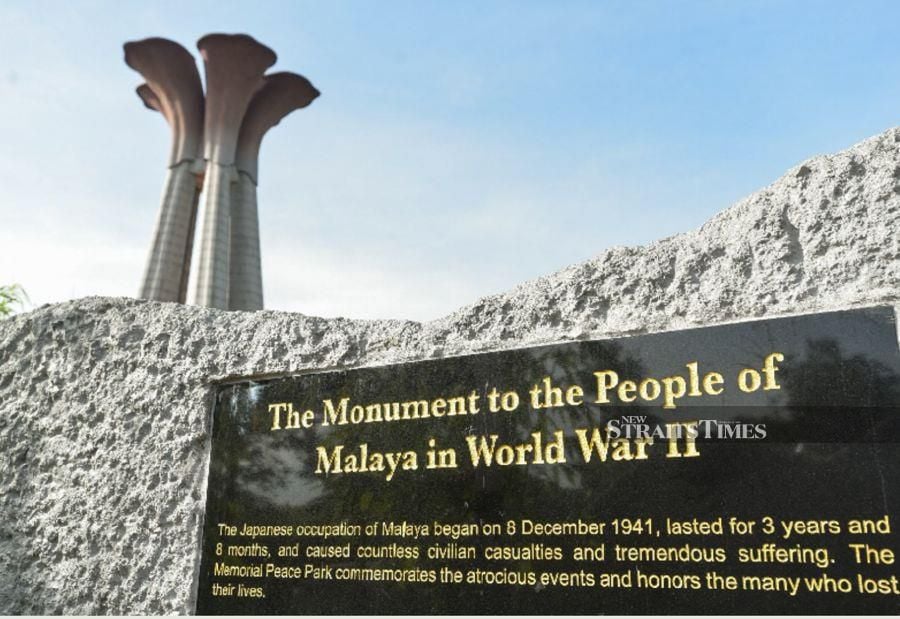

TRAGEDY OF SOOK CHING

"What was the biggest tragedy during the Japanese Occupation?" another question is fired in my direction as all eyes turn to me. After a pause to reflect, I recall my father's description of Sook Ching.

"Kill me, I beg you, please kill me!" The poor victims had cried to the Japanese soldiers, my father told me. They couldn't take the pain anymore. It was a total nightmare. The fearful residents of the town were made to parade around a few men whose faces were covered with their hoods. Just one nod from them and a whole family could perish.

Judging by everyone's expressions, I'm sure that they're thinking about the terrible sufferings and deaths of all those innocent Malayans during Sook Ching. "How did the Japanese torture their victims?" someone suddenly pipes up.

Recalling my father's deep anguish as he recounted the scene to me, I share the story of when the Japanese had forced my granduncle to lie down before proceeding to pump water into his mouth.

Once his abdomen was bloated, a few of the soldiers began jumping on him, causing water and blood coming out of his mouth, nose and ears. When he was half dead, the Japanese then hung him upside down from a tree under the hot sun. Finally, they bayoneted him.

Another common method, I remember hearing from my father, was to slice off the victim's fingers one by one. After that, the Japanese would chop off their limbs, again, one by one, until the victim died of massive bleeding.

Those who wore glasses and had English names were sometimes taken away and never to be seen again. "Why didn't the Japanese just kill them quickly instead of going through so much trouble torturing them?" someone muses aloud.

During Sook Ching, these mass torture and killings took place in all towns across Malaya and Singapore too. To this day, almost every major town would have a memorial commemorating the victims of Sook Ching and the war.

'DEATH RAILWAY' PROJECT

During a brief respite for lunch, I share with the group a story about my father's friend Ah Keong, and his lucky escape from the "Death Railway" project at the Thai-Burma border.

Out of an estimated 100,000 people, comprising British prisoners of war and Malayan civilians, half of them died of torture, disease and starvation. Keong managed to jump off the train that was bringing him and other Malayans to the work camp there.

During his escape, Keong had to spend the next few months trudging through thick jungle and trekking across mountains where tigers roamed. While crossing the crocodile-infested Perak River not far from Victoria Bridge, he nearly drowned after being shot at by some Japanese soldiers.

In the end, out of desperation, Keong joined the communists. Someone asks why he did it. I smile as I recall asking my father the same question as a child.

I still remember his words. He'd replied: "Millions of innocent Malayans suffered terribly. But the British had run away and there was no one to protect the innocent Malayans. Keong also hated the Japanese for raping his sister Yin. Having lost both her dignity and sanity, Yin subsequently committed suicide by jumping into a former mining lake."

JAPANESE SURRENDER AND BRITISH MALAYAN EMERGENCY

After two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, Emperor Hirohito finally announced the country's surrender on Aug 15, 1945. I recall how father had brightened up considerably when he described how overjoyed they all were to hear about the Japanese surrender. Tears flowed down everyone's cheeks.

When the British returned to Malaya, they did not want to share power with the communists. After the assassination of some British planters in Sungai Siput in 1948, the British colonial government declared the Malayan Emergency.

My father remembered that fateful day quite clearly. He told me that he was supposed to go there to pick up some rubber wood on that day. However, due to heavy rain, his lorry got stuck in the mud. As a result, he was late and had to rush back to his village before the curfew. Had he gone there on time, he could have been killed in the ambush too.

NEW VILLAGES

The Malayan Emergency turned out to be the longest war in the world at that time, stretching from 1948 to 1960. To cut off contact between the communists and farmers living in the jungle fringes, an estimated 600,000 Malayans were forcibly relocated to New Villages. They found themselves uprooted and squeezed into a totally alien and inhospitable environment.

During our visit to Temoh New Village, I recall my father's sombre tone when he described how life was back then. "In reality, the New Villages were more like concentration camps," he recalled, before continuing: "We were forced to live in double or triple barbed-wire compounds and were subjected to daily rations, curfews and surveillance. We lived in constant fear and had to face daily challenges and deprivations."

I also remember the time when he shared the story of his encounter with some communist guerrillas. Excitedly, he regaled: "One night, a group of communist guerrillas broke through our village's perimeter barbed wires to steal some guns from the police station. Spotting the communists making their escape, I opened fire instantly."

It so happened that my father was on home guard duty that night. However, instead of hitting the communists, he ended up injuring himself due to the strong recoil of the shotgun. It was unfortunate that the home guards were given outdated guns and had poor training.

This tour also brings to mind some of the stories that my aunts had told me about. I remember them telling me how they had to go out everyday at 5am to tap rubber. Each time they went through the village's exit gate, they had to be body searched by the armed male guards.

There were instances where their modesty was outraged. So fearful were my young aunts that they described the male guards as Ngao Tao Ma Mien or "ox head horse face"! My aunts had likened them to the guardians of the gates of hell.

DANGER AND CHALLENGES

Some of the people in the group express their curiosity about the challenges of living in the New Villages. I tell them another story, which my father had told me about the time when the communists wanted him to smuggle some rice and medicine out of the New Village using his lorry.

The penalty for smuggling such items was death. However, if my father were to refuse the communists' request, he would also be in danger. He ultimately had to decide between choosing his life or livelihood.

After giving up his lorry, my father went on to drive a bus. I remember him telling me about the time when halfway towards Telok Intan (Anson), his bus was "kidnapped" by the communists.

They ordered all the passengers to disembark before setting it on fire. Father's anger rose as he saw the rising flames engulfing his bus. Thankfully, no one was injured.

FACING A DILEMMA

When my brother joined the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) as a jet-fighter pilot, my father was caught in a personal dilemma. He was worried that his communist friend, Keong, and my brother might end up killing each other on a battle field. However, as it turned out, both of them died separately.

Tragically, Keong ended up being killed in a power struggle among the communists in Betong, Sarawak, after a lifetime of terrible hardship and constant struggles. In the end, it was a case of broken dreams and false ideology for him.

Unfortunately, my brother also died a tragic death. He was only 31 and had succumbed to his injuries from a car accident. We were all shocked and saddened by this tragedy.

Being the first-born son, my parents loved my elder brother the most. Little did my father expect that he would have to absent himself from my brother's funeral one day, just as his parents had done so at his baby sister's funeral during the war 50 years earlier.

Whenever I pass by the hills of Kampar and Temoh now, I can't help but recall the various events and incidents, which I'd written about in my book. The hills are alive again. And once more, I can hear the loud booms of the big guns and the mighty roars of the tigers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gary Lit Ying Loong, better known as Gary Lit, presents the memoirs of his late father in his latest book, If The Sky Were To Fall, which offers a stark account of key historical events through the eyes of an ordinary citizen living in Kinta Valley, Perak, during the wars of the 1940s and 1950s.

Set against the backdrop of the most turbulent period of Malayan history, Lit shares the stories that he had gleaned from his beloved father, Lit Kam Chong, who was born in 1929 in Malaya. The elder Lit had lived through the injustices of the colonial British administration, the atrocities of wartime Japanese occupation, the ensuing turbulent Emergency, the unsettling post-colonial aftermath and the subsequent economic stability and prosperity.

The book, a labour of love dedicated not only to his late parents (including his mother, Chew Yoke Cheng) but also the innocent villagers of San Chun, exposes the myths and mysteries surrounding this period, whilst attempting to offer us a better understanding of the subterranean forces shaping the people and country then and now.

"I had to wait for three events to come to pass before I could publish my father's memoir," confides Lit, elaborating: "The first was that the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) laid down its arms, and the second, the death of its leader, Chin Peng. The third was my father's passing."

IF THE SKY WERE TO FALL

By: Gary Lit Ying Loong

Published by: Gerak Budaya Enterprise

Pages: 310

For more details, go to www.gerakbudaya.com or email: [email protected].