IN Ayie's fingers a pencil sang of a long forgotten time, and a paper drank his thoughts in rhyme.

His trusty chair is rolled close to the tidy table, his head bends even closer still over the off-white surface.

So it is a "kabuto" takes form on the lined sheet, grim in its dark shades in the cold and desolate newsroom that night.

This writer looks over Ayie's hair-draped shoulder, and the artist wakes up from his reverie, breaking into a winsome smile.

It must have been a good dream, talent and heart journeying hand in hand on a canvas beyond space and time. The birth of the "kabuto" shows this to be true.

Ayie drew quite a collection in the moments of respite from the daily grind, or the battles, as some colleagues would say. In the trenches, when the figurative cannons and rifles paused to rest, he would be restless. And the pencil would come out.

Not unlike Tolkien, whose "grand conception", according to his grandson, "had to have been informed by the horrors of the trenches" of World War 1.

But Ayie, who was born in Bagan Serai, was not prone to grandiosity and pomposity. Not even when he won awards in national competitions.

He kept things in perspective. Winning and happiness were but interludes in life. Human beings make too much of success anyway, and too little of the rest.

And this he telegraphed to his son when the latter came home from school with SPM results that were not glittering like the bauble-filled certificates of so many others.

Ayie hugged him and said: "It's all right. Abah loves you." In doing so he embraced more than his son, and less of his milieu.

There was no scent of judgment, no scene of tears. Thus was Ayie not dissimilar to Pauline.

She came from a time distant, but she hardly spoke of the past. Only a glorious future was her upcast eyes seeking in the heavens.

The 77-year-old could laugh at anything, herself included. This writer thought she was as witty as Violet Crawley, Dowager Countess of Grantham. Though not as catty.

But she did not condemn — neither venom nor vileness left her lips in the 20-odd years this writer knew her.

After all, she believed there were no wicked people. Only troubled souls with trembling hearts. So she prayed fervently for others, and read scripture avidly for herself.

The former she did for hours on end, especially after watching the news on Al Jazeera. All the oppressed people of the world were her sisters, brothers, fathers and mothers. And all their troubles were her yoke to bear.

Here then, in Ayie and Pauline, was Wilde's compassionate nightingale, who "set her breast against the thorn… All night long she sang, and the thorn went deeper and deeper into her breast, and her life-blood ebbed away from her".

The little creature sang when the moon was high and heavy-hearted and haunting. No one knew her, no one mourned her.

Ayie and Pauline were not luminaries in the eyes of the world, as unknown as the flowers that grow like bejewelled pendants in the shadows of great mountains.

But they lived lives of purpose, giving life-blood to families and friends and faith.

And when the thorn finally pierced their hearts, one day after the other in September, they made that journey to Hamlet's undiscovered country.

In the hearts they leave behind, the pencil and prayers continue to sing of shades of light, and of lives that rhymed with purpose.

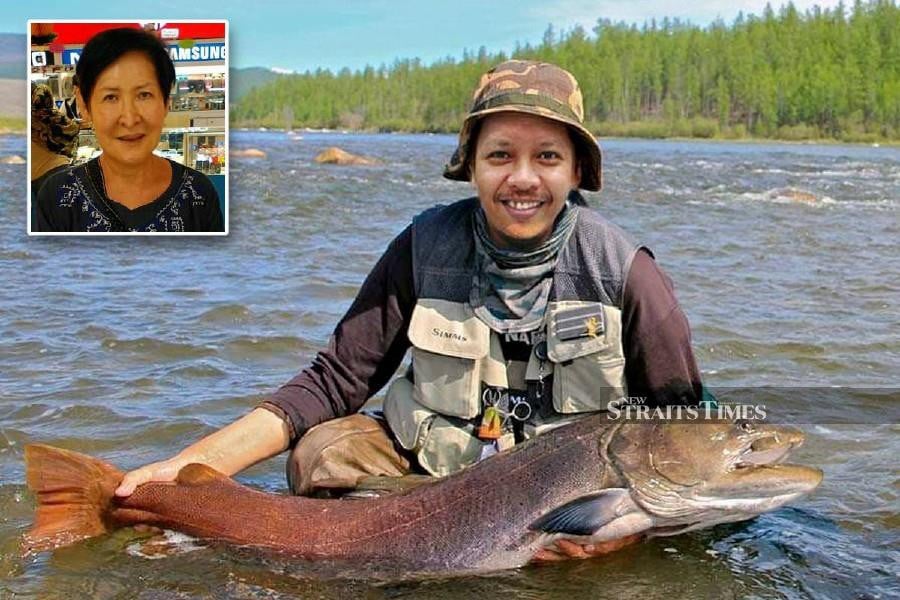

Ahmad Suhairy Shuib, or Ayie, had served in the New Straits Times as a graphic artist for 10 years.