MUSICIANS and sportsmen and sportswomen have played a commendable role in supporting political struggles whether it is for democratic rights and freedom, against racism or in support of gender equality and empowerment.

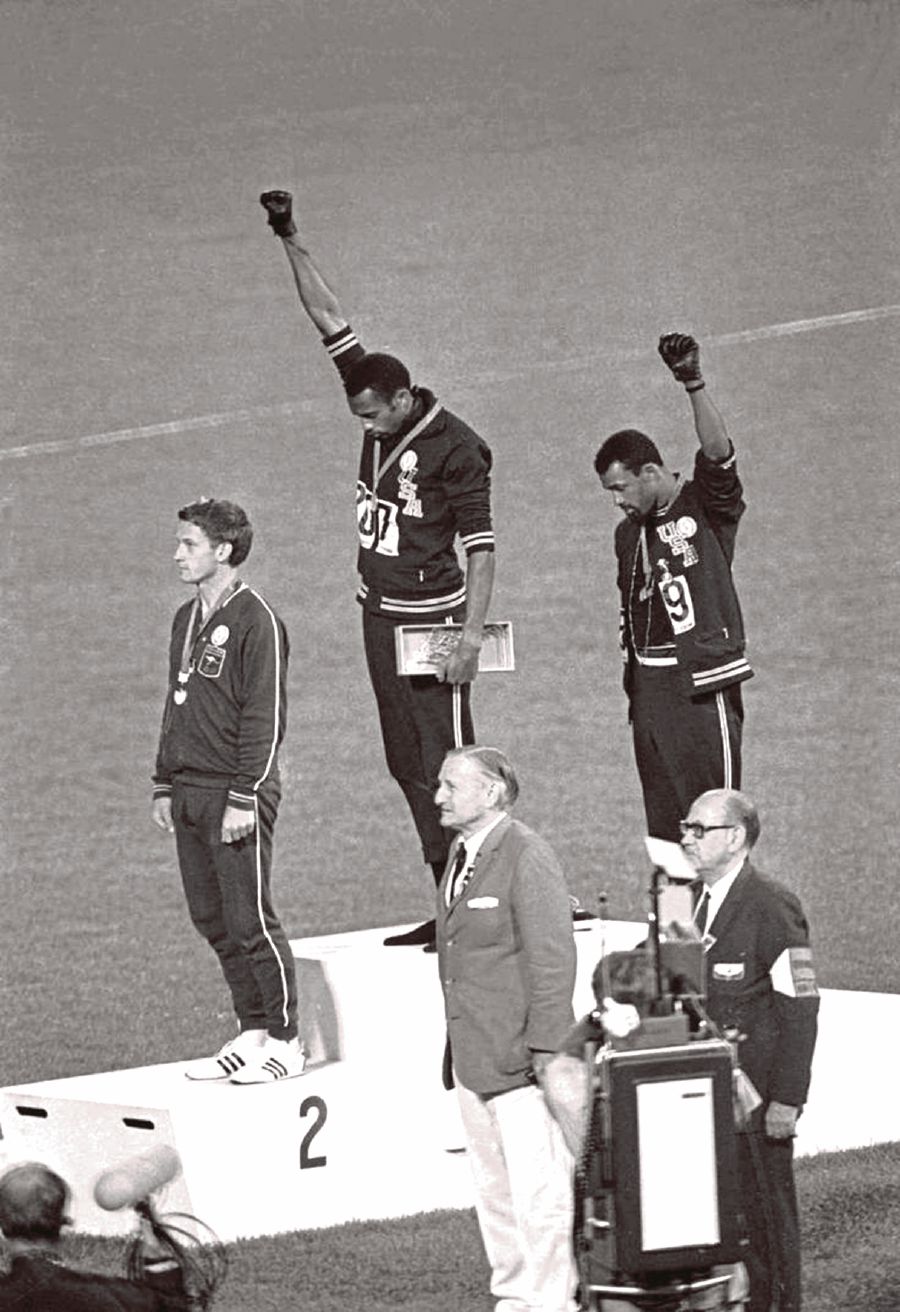

Jesse Owens exploded the Nazi myth of Aryan supremacy at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in front of a dejected Hitler. While Owens let his feet do the talking, others have been more forthright in their approach. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medallists in the 200m, stood with their heads bowed and black-gloved hands raised as the American national anthem played during the medal ceremony at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, staging a silent pro-test against racial discrimination.

Muhammed Ali refused to be inducted into the United States army fighting in Vietnam and was subsequently convicted in 1967 of draft evasion, sentenced to five years in prison, fined US$10,000, stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from boxing for three years.

Last October, Colin Kaepernick, then with the San Francisco 49ers, kneeled during the national anthem in an NFL game in an attempt to provoke debate on race and police brutality against African-Americans.

In the performing arts, Paul Robeson, the American baritone, was blacklisted during the McCarthy era in the 1950s for his in-volvement with civil rights movement and anti-fascist sympathies during the Spanish civil war; and Josephine Baker, the St Louis-born dancer and singer who became wildly popular in France and Europe during the 1920s, spent most of her life fighting segregation and racism in America.

The list is endless.

In the 20th century, Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa stood out with their oppressive racist policies. While the brutality of the Nazis is incomparable in modern history, people of colour in apartheid South Africa were living the humiliation and oppressive policies of white supremacy on a daily basis for over half a century. To think that apartheid officially ended only seven years shy of 2000.

Musicians and sports people, like other sections of society, were giants in the anti-apartheid struggle.

In late January, two of these giants, legendary jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela, 78, and leading figure in the anti-apartheid struggle Sulaiman “Dik” Abed, 74, the cricketer who, among others, paved the way for the isolation of the apartheid-era South African national team, the Proteas, and its subsequent rehabilitation in international cricket following liberation when the jailed ANC leader Nelson Mandela was released in 1993, passed away peacefully after long illnesses.

Lest we forget, the likes of singer Miriam Makeba, jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, rugby player Cheeky Watson and countless others valiantly fought against apartheid for years. But, it was “Bra Hugh”, Masekela’s endearing soubriquet, who gained global recognition with his distinctive Afro-Jazz sound and hits, such as Soweto Blues in 1977, which became synonymous with the anti-apartheid movement (AAM).

That unique style was encouraged by the great Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong, under whose tutelage in New York Ma-sekela, aged 21, prospered since leaving South Africa in 1960 to begin 30 years of exile from the land of his birth. His talent was exceptional and his rise meteoric, for only seven years later he appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival alongside Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, The Who and Jimi Hendrix, only to release his instrumental single Grazing in the Grass a year later, which topped the charts in the US and became a worldwide hit.

“I was kidnapped by music,” he surmised in a BBC interview.

“It was an anaesthetic against all the pain and violence in South Africa.”

Perhaps it was fate that brought together the young Masekela and Father Trevor Huddlestone, a teacher at the St Peters missionary school near Johannesburg.

Masekela was always getting into trouble.

“What can I do to help you,” asked Huddlestone, who went on to become archbishop and the head of AAM in Britain after being expelled from South Africa by the apartheid regime.

“If you get me a trumpet I promise to stay out of trouble,” retorted Masekela.

The rest is history.

Ever since seeing Kirk Douglas play Bix Beiderbecke in the 1950 cult film Young Man with a Horn, Masekela decided that the trumpet and music was his calling.

His spectacular global success and fame prompted the apart-heid regime, wary of the bad publicity in the West, to add insult to injury by urging him to return to South Africa as an “Honorary White”.

Masekela was a consummate South African patriot, claiming that despite being “physically overseas, spiritually I had never left”. He continued to champion the cause of his compatriots who had been left behind in post-apartheid South Africa by successive ANC governments till the end.

“Democracy means nothing if my people are not free and there is no economic victory,” he said.

Sulaiman Abed, in contrast, was the youngest of a famous Cape Town sporting family, who similarly made his name in exile in England playing cricket with his brother Goolam in the Lancashire League in the 1960s.

They, together with Basil D’Oliveira, who went on to play for England, and a spate of South African non-white cricketers pulled off a massive achievement to get the Lancashire clubs to take them on as “unknown” pros at a time when established players, like Sir Garfield Sobers, Clive Lloyd, Charlie Griffiths and Wes Hall, were playing in the league.

Abed, too, was courted by the apartheid regime to play in South Africa, but, like Masekela, told the officials to get lost. He took up Dutch citizenship in the mid-1970s and captained the national team that played at the second ICC Trophy competition in England in 1982.