FOR a man who once famously swore that “only God” could remove him from office, Zimbabwe’s 93-year-old president, Robert Mugabe, a practising Catholic, could always rely on his charismatic defiance.

Despite his frailty, he was on course to seek re-election as the official candidate of the ruling Zanu-PF party in next year’s presidential election.

In the liberation struggle against white minority rule in the then British colony of Southern Rhodesia since the 1970s and his subsequent elevation to becoming Zimbabwe’s first and only post-independence black president on April 18, 1980, it worked like a treat especially for the supporters of the dashing young war veteran.

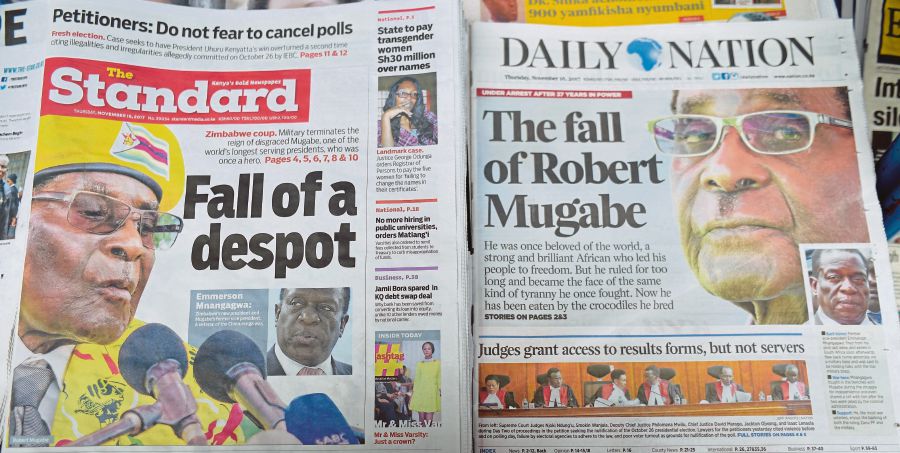

But, after 37 years and seven months in power, his luck and his “prophecy” finally seems to have run out. Thanks largely to the army led by Chief of Staff General Constantino Chiwenga, whose soldiers seized the state broadcaster Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC) on Tuesday and confined Mugabe to his home in Harare, effectively under house arrest.

South African President Jacob Zuma, the only leader to speak to Mugabe since the army action, confirmed that the Zimbabwean leader “was confined to his home, but said that he was fine”. Despite uttering to the contrary by the army, this was a coup in all but name. Even the African Union, the grouping of 55 African nations, stressed that “it seems like a coup”, and called for a restoration of constitutional rule.

Post-independence African rule has been littered with military coups ranging from most of the Maghreb countries except Morocco, which is an absolute monarchy, to Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Ghana, Zaire, Guinea, Mozambique, Uganda and Angola the main countries plagued by intermittent military rule juxtapositioned with civilian governments. Zimbabwe is no exception.

Notable exceptions to the above governance phenomenon are largely the southern and east African nations of South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, Kenya and Tanzania. As such, the current developments in Zimbabwe are a major disappointment for both the elderly liberation veterans and the young modernisers, who are keen on leveraging the country’s huge economic potential. After all, Zimbabwe used to be the breadbasket of Africa.

But, years of cronyism, corruption and mismanagement under Mugabe’s watch and underpinned by the politics of race, decimated the economy, which the International Monetary Fund stressed at one stage was in “meltdown”. The result was year-on-year inflation that exceeded 1,000 per cent in 2006, eventually forcing the government to abandon the Zimbabwe dollar for a multicurrency basket dominated by the South African rand and the US dollar.

What is happening in Zimbabwe is an archetypal power struggle over who succeeds the frail Mugabe. The rivalry between his wife, Grace, 40 years his junior, and the erstwhile vice-president Emerson Mnangagwa has split the governing Zanu-PF coalition. The South African-born and Chinese-educated Grace had unceremoniously sacked Mnangagwa earlier this month.

Grace’s ambition to be the next leader of Zanu-PF, thus initiating Africa’s latest ruling dynasty, proved too much for army chief General Chiwenga, who happens to be a friend of Mnangagwa. Despite the army’s contention that it acted to “end purges within Zanu-PF” and “criminals” around Mugabe, its role as the honest broker may be compromised.

Zimbabwe seems to have fallen prey to the politics of succession, especially after a charismatic ruler whose autocratic rule survived only with the support of the very army, which now sees fit to oust him.

Another interpretation could be that the army is merely trying to reassert the original Zanu-PF political ethos, which puts the people and interests of Zimbabwe first.

Chris Mutsvangwa, the leader of the Zimbabwe war veterans and Mugabe’s comrade during the liberation struggle against the white-minority rule of prime minister Ian Smith, could not have put it more aptly, “It’s the end of a very painful and sad chapter in the history of a young nation, in which a dictator, as he became old, surrendered his court to a gang of thieves around his wife,” he told Reuters.

In the words of Nobel Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the anti-Apartheid campaigner, Zimbabwe’s long-time president had indeed become a cartoon figure of the archetypal African dictator.

But, why did Mugabe go down this route? His alma mater after all is the “black only” apartheid-era University of Fort Hare in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, the same as those of African liberation giants Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, the stalwarts of the African National Congress (ANC), and Robert Sobukwe, the leader of the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC).

Mandela, Tambo and Sobukwe, who all served lengthy incarcerations at the notorious Robben Island prison, off Cape Town, emerged as giants of the African struggle for freedom.

But, Mugabe’s legacy will be tainted by the excesses of his later rule, his ruthless elimination of political rivals, including his former friend Joshua Nkomo, and his slide into autocracy tempered with cronyism and a near-obsessive hatred of the British political establishment.

As for the immediate future of Zimbabwe, the spectre of the 75-year-old Mnangagwa ushering the country into the 21st century is not awe-inspiring.

At best, he and opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, who defeated Mugabe in the 2008 presidential vote, could only be stop-gap holders of the presidency.

The world is moving towards a much younger leadership demographic, the likes of Macron in France, Trudeau in Canada, Muhammed Bin Salman in Saudi Arabia, Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand and Sebastian Kurz in Austria. There is no reason why Zimbabwe and Africa, too, could not skip a generation or two in this respect.

Mushtak Parker is an independent London-based economist and writer. He can be reached via [email protected]