LIVING up on a tiny hill station has always held a certain appeal for me. Illusions of pioneering adventures and halcyonic rusticity abound. Not to mention the exclusivity of an address with a mere smattering of neighbours whilst still having the option of rolling down the hill for a quick Indian take out.

It's the desire to "play house" in a simpler setting, in which raw experience is everything… despite my mid-level dislike of frogs and the fear that monkeys might smell the cheddar crisps in my handbag.

The reality of my experience of Bukit Larut, however, has been restricted to a single 45-minute hike up to Watermelon Point. Unstable weather conditions have meant that the recently opened hiking trails are often off limits, and at the time of writing, ditto the tarmac road to the top.

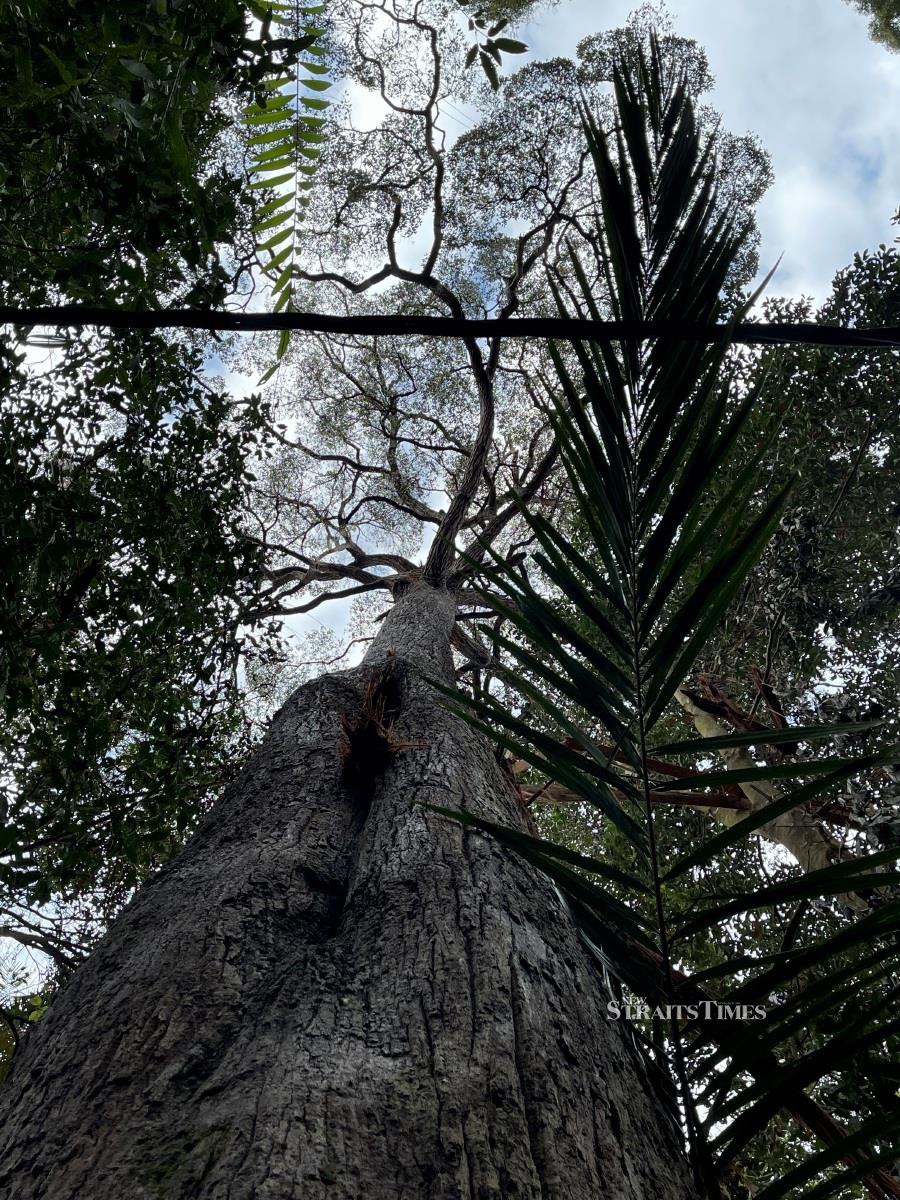

Because weather conditions have dictated that Bukit Larut is often an extravagantly waterlogged windswept superhighway, it has remained, since its establishment in 1884, small and underdeveloped, unlike other larger hill stations in the country that are sliced up and slated for grandiose development with little attention to environmental issues.

And whilst the old colonial bungalows at the top do await some tender loving rehabilitation, the flipside of this is that Bukit Larut is one of our least disturbed natural sanctuaries. The steep terrain induces the highest rainfall and water catchments in the country, creating an ecologically sensitive area not exactly suitable for mass agriculture or development that could disturb the natural balance of the surrounding ecosystems.

As such, wildlife flourishes. Some of the 25 species of mammals found here include the dark-handed gibbon, the clouded leopard, the flat-headed cat, the white-bellied rat and the leaf horseshoe bat.

Amongst the more than 200 bird species are helmeted hornbills, black eagles and peregrine falcons. Migrant visitors like Japanese sparrowhawks, barn and red-rumped swallows and the Siberian thrush have also been sighted. And just for good measure, the atlas, the world's largest moth, and one of the world's loudest insects, the empress cicada, have also chosen to take up residence on the hill.

There's richness and simplicity in assessing life on the hill. An appreciation of life shaped by landscape and nature, and if you get it right, coming back down the hill with a fuller heart and mind. But, perhaps to find out more about the reality of living up on the hill, I had to have a chat with one of its very few residents in more recent years, Liew Suet Fun.

THE NEST

A writer with 19 books to her name, Liew was born and raised in Taiping before "living several lives everywhere else for work and studies". Always knowing that Taiping would be her eventual home, she returned seven years ago with her husband Peter Matu, a Kelabit from another highland, Bario, in Sarawak.

As a child, the then Maxwell Hill was a special place of intrigue and mists for her as it was for most of the small town. She visited the hill often as a girl, and knew of the 10 or 11 small homes that had been developed exclusively for colonial officers in the 1880s.

The property that was to become her home years later was called The Nest. It became a retreat for the Methodist Mission in 1904 when its first resident, John Fraser of F&N, left and offered it to the mission. There was a hierarchy amongst the bungalows then, with the highest (now the telecom tower) being given to The Governor.

b

Next came The Box — used exclusively by The Resident of the day — and then, The Nest. When the British left, Maxwell Hill still carried a little English mystique. Railway journals advertised it as a popular destination and a desirable honeymoon location.

Liew and Peter moved into The Nest in 2016, when the church was looking for someone to take it over and run it as a guesthouse. They re-opened the fireplace, carried out some renovations and turned it into their four-bedroom home.

Shortly after, they opened their doors to paying guests a couple of times a week. The Nest sits slightly back from the tarmac road, making it only accessible via a footpath. Liew and Peter spent three extraordinary years traipsing this path with supplies for themselves and their guests.

Visitors are given a little speech about the history of the hill and their home when they arrive to connect them to their surroundings. But what Liew has seen is that they'll all find their own connection. There's a magic that captivates everyone and leaves them protective of this mystical place.

This is forest bathing 1,219.2m above sea level in its most pristine form. Guests are truly transformed. And children especially discover true connectivity that doesn't require 4G. Mission accomplished really if a life-long love and understanding of preserving nature is instilled.

For some years, Liew and Peter really were the only full-time residents of Maxwell Hill. They loved that from Taiping town centre they could reach the top of the hill in a land rover within 30 minutes, in a fascinating transition from lowlands to highlands.

At the tail end of the Covid-19 lockdown last year, a powerful storm ran up the hill leaving a path of destruction, triggering landslides with the risk of even more to come. The hill became inaccessible and they stopped living there full-time, returning to live in Taiping town.

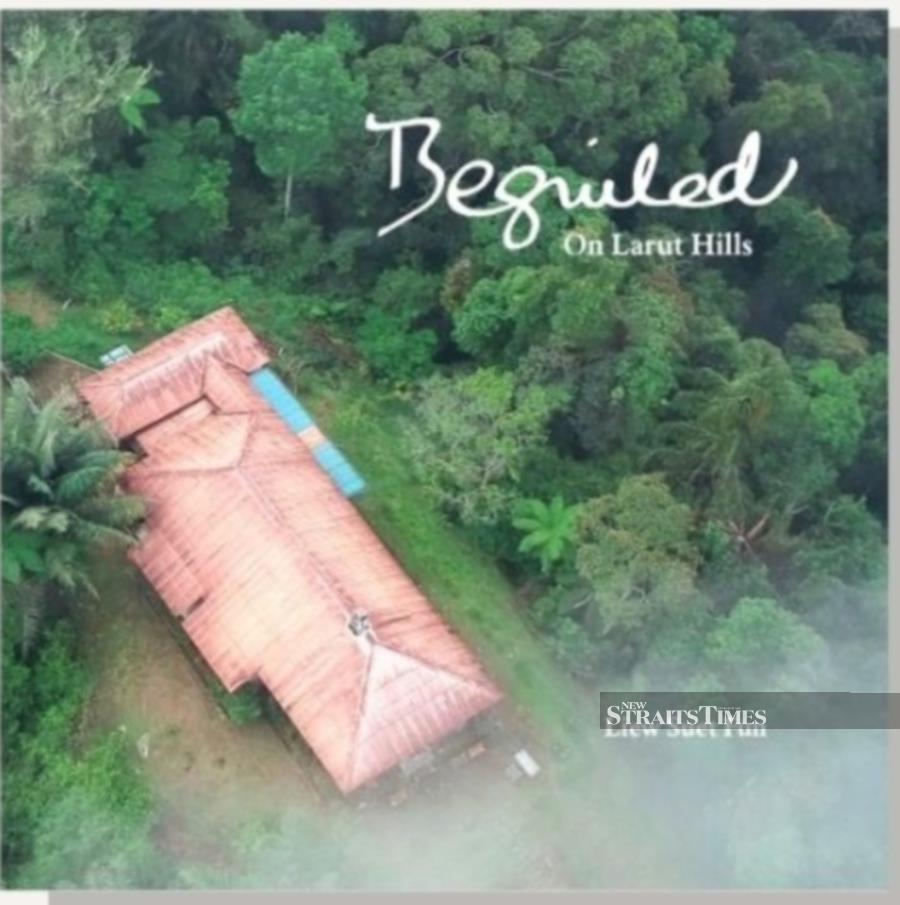

Naturally, being a writer, a book grew out of her great love for this hill. Beguiled, published in 2020, is a fact-based book from a very personal perspective. A narrative about "these forest-clad mountains, inhabited by ancient fern trees, delicate mosses, giant palms and hidden waterfalls. Of the rambling timber bungalows, a steep road of 72 hairpin bends and old footpaths drenched in mist and cloud".

A space of curious wonderment that served as a counterpoint to the very different world down the hill, the book is "a meditation on the power of a landscape and how such a place remains our geography of hope".

It's also a memoir of the human stories of the old Keralan caretakers as told by their families. Liew believes their oral history is invaluable and needed to be recorded. Her weaving together of all this has been a gift to the people of Taiping.

DOWN THE RIVER

And if one were to follow the torrential trails fed by the catchment of Maxwell Hill, downstream all the way to the Straits of Malacca, one could end up in the coastal towns of Matang and Kuala Sepetang.

Lying a mere 15km from Taiping in the opposite direction, it took my enthusiastic guide, Anis, barely 20 minutes by car, negotiating the tidal waters that had started washing up on the roads.

A quick stop for the best Mee Udang Banjir by Mak Teh (look out for the signboard) is always a good idea before hitting the gorgeously preserved Matang Historical Museum. Once home to Ngah Ibrahim, who carried the title Orang Kaya Menteri Paduka Tuan, it was his father Cek Long Jaffar who opened the first tin mines in 1840.

The Matang Mangrove Swamp Forest Park is the gateway to the largest unbroken expanse of mangrove swamp forest remaining in Peninsular Malaysia and one of the best managed in the world. The Matang Mangrove Eco-Educational Centre leads you along a boardwalk to get up close with the forest and disburses important information on our critical mangrove ecology.

A hop onto a river cruise along Sungai Sepetang is really then required. One may or may not spot pink dolphins along the way, but your boat operator will guarantee a feeding of the eagles.

There's cockle and fish farming to be seen, but really, the most fascinating stop is the Teochew Village of Kuala Sangga, infamous in the old days for its safe-housing of pirates. Only accessible by boat, the tiny, roughly-hewn but surprisingly organised village of fewer than 20 families today still doesn't have regular electricity supply and survives on rainwater.

A few dozen wooden houses line the shore waters as fishing nets and laundry are laid out to dry under the scorching sun. Most outstandingly, it has a school with classrooms and a multi-purpose hall which, at the time we visited, had ONE student aged 8. A teacher visits by boat from Kuala Sepetang every weekday just to oversee his education. How's that for a daily commute?

It's then back on the mainland for a sumptuous seafood lunch at one of the many picturesque restaurants that line the sea front and the charcoal kilns. Canals transport the felled mangrove logs from the nearby forest to these tiny family-run factories in a setting so idyllic that production houses shoot movies here.

Charcoal is manufactured in the old-fashioned way by smoking the mangrove logs for around 30 days in enormous brick kilns. The premium grade charcoal that results has a shiny veneer and little soot and is most often exported to Japan.

It's possible to visit the charcoal factories for a tour and to purchase the many charcoal products — from toothpaste to insect repellent, and more. Seriously, charcoal foam hair conditioner? Okay maybe next time. Any old excuse to return will do — thank you!

This feature was commissioned under Think City's Cultural Economy Catalytic project for Lenggong, Kuala Kangsar and Taiping in Perak, Malaysia. The opinions expressed here are solely the author's and do not reflect the opinion of Think City.

To read Beguiled, go to www.gerakbudaya.com/beguiled-on-larut-hills.

To contact guide Anis Sabhee from Nezzworx Marketing Resources, call 019-357 5721.

For Port Weld Eco River Cruise, call 016-561 4444.