IT'S a singing competition unlike any other. Yet, the premise remains the same. Loud, boisterous crowd yelling their support. Enthralled audience and serious judges circle the ring where the singers are put through their strides.

That's where the similarities end. Hanging at the pavilion are cages where the singers are confined. And standing 50 feet away are the owners shouting at their singers to elicit their best songs while hurling abuse at the judges.

Inside one of those gilded prisons, a delicate little bird tries to sing its best song under tremendous stress. It's one of the many singers trapped in cages, attempting to "perform" in a warped version of "Avian Idol" that has become a lucrative business across several Southeast Asian countries for decades. Ostensibly, it's a battle of the birds. But there is just as much grandstanding by their handlers vying for trophies, cash prizes and prestige at tournaments or impromptu matches.

Owning a champion bird "singer" isn't simply a matter of pride. Winners receive television sets, motorcycles, cars and cash prizes worth hundreds or thousands of dollars. The winning crooners are worth a whole lot more, which in turn, does not bode well for these feathered creatures.

Millions of songbirds are stolen from the wild every year. These birds are not treasured for their plumage or meat, but for their songs. The illicit trade first begins in the primeval forests of Malaysia, Thailand and neighbouring countries, and ultimately enters into high-stake singing competitions both locally and across borders — if these birds survive the terrifying and often fatal ordeal of being smuggled.

Officials and conservationists say wild songbirds are disappearing at a tremendous rate across Southeast Asia. Much of the demand is fuelled by the growing craze for bird-singing contests in Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and even Malaysia.

"These competitions are driving quite a lot of the trade here in Southeast Asia," says Serene Chng, the senior programme officer of Traffic, a leading non-governmental organisation working globally to monitor the trade of wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

As a wildlife trade researcher, Chng's research of songbirds has brought many emerging wildlife trafficking issues to light in more than 24 publications and at talks in film festivals and international conferences.

Her extensive research has earned her a grant from National Geographic to investigate the bird trade at the Malaysian-Thailand border, which earned her the National Geographic Explorer moniker in the process.

Chng's work has also been instrumental in galvanising a range of conservationists, researchers and policymakers to address the bird trade as a serious conservation issue. This has led to the formation of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission Asian Songbird Specialist Trade Group, of which she is one of the coordinators.

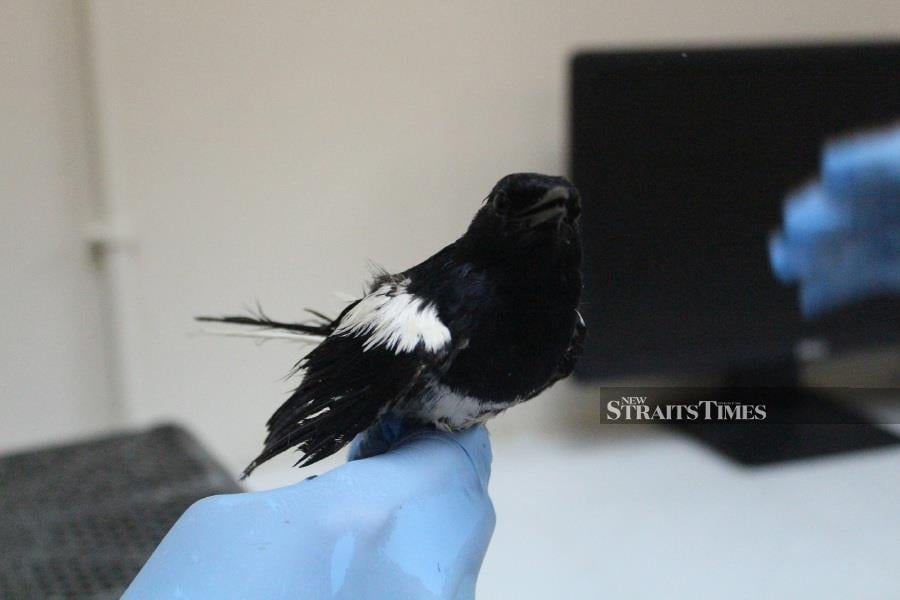

The recent report entitled Smuggled for its Song: The Trade in Malaysia's Oriental Magpie-robins, which was authored by Chng and her compatriots in Traffic on the smuggling of the Oriental Magpie-robin — a popular songbird in the region — showcases the danger that these birds face at the hands of trappers and smugglers simply because of their superior vocal cords.

Several of the songbird species already feature in IUCN's List of Threatened Species. So many birds have been whisked from the forests of Indonesia that more than a dozen species are in danger of extinction, like the Straw-headed Bulbul. Traders are now ransacking the forests of Malaysia and Thailand, too.

"Songbirds like the Oriental Magpie-robin are headed for trouble if they're not protected from rampant trapping in Malaysia and smuggling to feed international demand," she warns.

VOCALISTS OF THE WILD

The melodic and diverse songs of songbirds frequently inspire pop songs and poems, and have been doing so for centuries, all the way back to Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet or The Nightingale by H.C. Andersen.

Songbirds, explains Chng, belong to an order of perching birds called passerines, which share a distinct toe arrangement that helps them grasp branches. "The arrangement of their toes — three pointing forward and one pointing backwards — helps them perch on a branch easily," she adds, smiling.

Despite their variety in size and musical talent, all songbirds have something in common: precise control of a highly specialised vocal organ called a syrinx. Almost all birds use a syrinx to produce sound, but songbirds have superior mastery of theirs.

The big difference is not the syrinx itself, but the muscles around it. These songbirds have a whole series of really complex muscles attached to the syrinx, and it gives them much greater control in singing.

It's amazing to think that we have such a melodic bird that can really sing, I muse and Chng nods enthusiastically, replying: "It's analogous to the human voice box, but it's a lot more complex and that's why songbirds can have some of the most complex songs and calls in the bird world."

There are thousands of songbirds across the world, but some are especially in demand due to the quality of their "song". It's that talent that has put songbirds like the White-rumped Shama, Straw-headed Bulbul and the Oriental Magpie-robin on the "hot list" of birds that are illegally trafficked across Southeast Asia.

Not all songbirds are put through the competition rounds, clarifies Chng. Some are also kept as household pets, pushing several of the most popular species toward extinction. "People keep caged birds for a variety of reasons," she says, adding: "Sometimes it's a tradition that has been handed down by their own fathers and grandfathers."

For whatever the reasons, whether they are being competed in singing competitions or simply kept as exotic pets, the illegal trafficking of songbirds has been quite concentrated in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam.

The demand for songbirds is so great that a thriving black market has developed, and smugglers have taken great efforts to evade laws on animal protection and quarantine.

THREATENED WITH EXTINCTION

The Traffic report by Chng reveals that the majority (64 per cent) of seized birds were being trafficked from Malaysia to Indonesia.

The Oriental Magpie-robin is common in the wild in Malaysia and other range states. You can see this distinctive black-and-white bird everywhere, I tell Chng and she nods. "They are fairly abundant but it's worrying to see just how many of them are being trafficked," she replies.

The report states that large numbers are being intercepted in seizures, with at least 26,950 birds confiscated in just 44 incidents that implicated Malaysia from January 2015 to December 2020.

This indicates that Malaysian Oriental Magpie-robin populations are being increasingly targeted to feed demand in neighbouring countries, particularly Indonesia. At least 17,736 (66 per cent) of all birds were confiscated in just 2020, signifying a current and possibly growing problem. This could be due to an increase in enforcement effort, coupled with dwindling populations in Indonesia to supply birds for trade.

The rampant trapping and trafficking of wild species can result in wild populations depleting quickly. "What songbird is most affected by the wildlife trade?" I ask curiously. "There's really no easy answer to that question," she replies, adding: "Because the species that are traded tend to shift over time. This could partly be due to the fact that certain species that were so popular have become so rare because there is such high demand and so much trapping that they are increasingly hard to find in the wild anymore."

In recent times, reveals Chng, researchers have discovered a new and rare sub-species of the White-rumped Shama called the Langkawi Shama that's indigenous to Langkawi and its surrounding islands. This species of songbird has been the subject of extensive specialised poaching efforts, and its continued survival is now at risk and in need of immediate conservation action.

The Oriental Magpie-robin was trapped to near-extinction in the wild in Singapore in the 1980s and required a conservation reintroduction programme to reverse the trend.

Chng cites the Straw-headed Bulbul as another example. "They have become extinct in Java and Thailand, close to extinction in Sumatra and are increasingly rare in Kalimantan and Malaysia as well. Where there is strong trapping pressure, the birds are harder to be found and mostly likely could head towards extinction in the wild."

History has shown that when trade of sought-after species is not properly regulated, wild populations can be depleted quickly like the Bulbul, which has now vanished from much of its range.

"So, now you probably won't see the Straw-headed Bulbuls in competitions. Instead, you'd probably see the demand shifting to other species like Greater Green Leafbirds, Grey-cheeked Bulbuls, White-rumped Shama and in recent times, the Oriental Magpie-robin," shares Chng.

FIGHTING THE SCOURGE

With increasing demand for songbirds from other countries, the real horror lies in the act of smuggling these delicate passerines. "When the bird is trapped in the wild, they are then smuggled and transported to the markets where the traders sell them to buyers. Along that process, a lot of these fragile birds will perish," says Chng soberly.

Stuffed into PVC pipes or densely packed into crates or fruit boxes, live birds in the illegal trade often don't survive the journey. The priority of the traffickers is to reduce detection, points out Chng, so they tend to hide these creatures in cramped compartments. "Sometimes this means hiding them near the engine of the bus where temperatures can soar and these birds die," she says.

By the time the songbirds reach the end point, there is a whopping 30 to 90 per cent mortality rate, That, adds Chng, will have a big impact on the wild population. For every one bird that safely reaches the hands of a collector, dozens of others often perish in transit.

Even if law enforcement officials do manage to intercept live birds, the stars have to align to return them to the wild: Officials must know where they are from, how to get them there, and how to ensure safety for the individual bird, other wildlife and humans.

This is rarely possible. So instead, zoos and other wildlife rescue groups struggle to provide lifelong care for these creatures in facilities already at capacity. In some cases, confiscated wild birds can neither be released nor properly cared for in captivity, and they must be euthanised.

From barely surviving the journey, these birds are further stressed as they're packed in hundreds of wire and bamboo cages, strung along awnings and crisscrossing the ceilings of cramped open-air stalls at Indonesia's thriving bird markets.

The 34-year-old tells me that her first field assignment involved counting almost 20,000 birds sold in wildlife markets in Jakarta, Indonesia. "It's like a pasar pagi, a wet market concept but instead of fruits and vegetables, they sell these birds," describes Chng who admits that the experience was overwhelming in its sheer magnitude, where songbirds are traded openly on a large-scale basis.

"It's like a sensory attack," she shares, adding: "The smell of the birds, the cacophony of birdsong, the humidity and seeing all these birds in cages... But it's important to see these realities for myself. Otherwise, how can I write my reports?"

How indeed? Experience is often needed as inspiration, but her job as a wildlife researcher has mostly comprised hours of analysing data and writing reports. "It's not very glamorous," she freely admits with a smile.

"What's a day in the life of an explorer like?" I ask curiously. She breaks into laughter, exclaiming: "Haiyo, it's really not that exciting lah! It's a lot of Excel spreadsheets, Word documents, writing and replying emails, to be honest!"

She shrugs her shoulders and continues seriously: "It's very much desk-bound. There's a lot of coordinating, talking with people in the field and our partners. We share our findings with the authorities so they can use that information in carrying out enforcement, as well as including them in the revision of laws and policies."

So, no hanging from the cliff or exploring deep impenetrable jungles then, I quip. She shakes her head half-regretfully. "I do sometimes wonder what's the use of me writing up all these reports. But then, I hear my partners come up and tell me, 'Serene, we shared your report with the local officials and they've agreed to change some things!' and I realise that there are people who are actually reading my reports. Raising the profile of these songbirds is equally important work," she says.

The Singaporean researcher credits National Geographic documentaries as her inspiration when she was young. "Those documentaries were the first things that sparked my interest," she reveals, adding: "Being called a National Geographic explorer and receiving a grant is such an honour, especially since they inspired me to get into the field in the first place!"

The conservation field wasn't an easy path to take, she admits, but knowing that she's making a difference has been one of the biggest rewards. "I've been working on this for nine years," explains Chng, before acknowledging that progress can be slow.

"It takes years to see any marked difference," she reveals candidly, adding "But there are positive changes taking place. Whether it's a single step forward, it still makes a difference for these songbirds. That's the most important thing. Small wins maybe, but we'll take it gladly."

The plight of the songbirds may be dire and the job may be thankless, but in Serene Chng's capable hands, they may not quite be ready for a final encore just yet.

Visit https://linktr.ee/expedition.earth to tune into Serene's podcast episode — Expedition: Caged. New Expedition: Earth podcast episodes are released every Friday at 5pm.