WADING through the plume of smoke emanating from a heated wok at the corner, my father and I made our way to the only available table in sight. At just after 10am, the morning crowd at the nondescript kopitiam (coffee shop) was steadily thickening.

The thin veneer on our wood table was chipped; my plastic chair stuck to the back of my legs. And the diminutive man who materialised as soon as we sat grunted with impatience when we paused to think before ordering. I understood his impatience. After all, the shop only sells one thing.

And yet, when our plates of blackish, glistening kuey teow with its generous cockles and chee yau char (pork cracklings) showed up soon after, I recognised the moment for what it was: a perfect kopitiam experience right here in the quiet neighbourhood of Melawis, Klang.

The clang of the ladle against the wok cuts through the bustling restaurant. "Eat!" my father instructed me briskly, pushing one plate of char kuey teow towards me. It's the shop of my childhood. A place where we were guaranteed a hearty plate of dark stir-fried flat rice noodles with bean sprouts, cockles and prawns.

The spry looking uncle would greet my father with a brisk wave, take down our orders ("kasi pedas sikit!" (make it a bit spicier!)) without writing them down, and then return to take his place at the smoky stove again. There's a deluge of orders, but he remembers each one of them precisely.

Memories of those visits faded as time went by. My father passed away four years ago and I never made the trip back to that shop in Jalan Melawis since then. But the shop plodded on stubbornly through the years.

It remains one of Klang's last bastions of nostalgia, serving up the same plates of char kuey teow for more than five decades — a hidden card trick of a town that's determined to preserve some of its finest secrets despite the changing tides of time.

The shop still looks remarkably well preserved. Nestled among a row of single-storey shoplots, there's no morning crowd thronging the darkened space inside. The kuey teow shop is closed today. But uncle Ng Seng Kiat is standing there at the half-opened shop to greet me.

Ah, that smile is familiar. He doesn't recognise me, of course. Time has flown indeed. Thousands of people have passed through his restaurant and he'd be hard-pressed to recollect every single one of them.

"I've come here with my father before," I tell him in Bahasa. He nods and smiles. He's not surprised, of course. If you're a bona fide Klang-ite, you would have — at some point or the other — found your way to Melawis to sample his famous dark kuey teow.

"Do you like it?" the 83-year-old asks me in his broken Malay. "Of course!" I reply, grinning. "You must come back tomorrow to eat my char kuey teow," he tells me pointedly. It's an easy promise to keep.

TRADITIONAL FAMILY SECRET

It's definitely difficult to resist a good plate of char kuey teow. The flat mee in char kuey teow are fried with crunchy lard croutons, prawns, cockles, bean sprouts and chives.

You know that the char kuey teow is good when you can taste that charred and smoky flavour rendered by extremely high flames and a well-seasoned wok. The cooking technique employed by experienced cooks like Ng is also known as wok hei meaning "breath of the wok".

Ng's offering differs from the more popular variation that's a staple Penang offering. "What makes a good plate of char kuey teow?" I ask Ng. He thinks for a moment and then chuckles. "The secret is in the sauce and the wok hei of course," he finally replies.

His dish isn't the same as what's being offered in Penang and Singapore. "Tada serupa (not the same!)!" he insists, adding: "The Penang version is paler and usually cooked in light soya sauce. Singapore one is sweeter in taste, but my kuey teow is cooked in dark soya sauce," he explains. The sauce concoction is, of course, a family secret, he adds with a beam.

The "black" char kuey teow used to be a popular offering back in the 1950s right through the '70s, but Ng is probably among the last handful of cooks who employs this traditional version of the dish. "It took a lot of trial and error, and learning from other fellow hawkers," he reveals, shrugging his shoulders.

Back then, they used mangrove wood to fire up the stove. "That added a lot of flavour to the kuey teow," he says, before lamenting: "Now everything is electric or gas. You can't find those type of wood anymore. Again, we have had to adapt to modern times!"

He's clearly not a fan of modern times. "Everything is expensive now!" he exclaims. "Cockles were cheap then. We used to buy them by the kilos for so little. In fact, the road outside my house was paved with cockle shells! Now, cockles are so expensive and cost of ingredients have skyrocketed over the years."

His face clouds over. "Everything is changing rapidly," he says quietly.

OLD MEMORIES

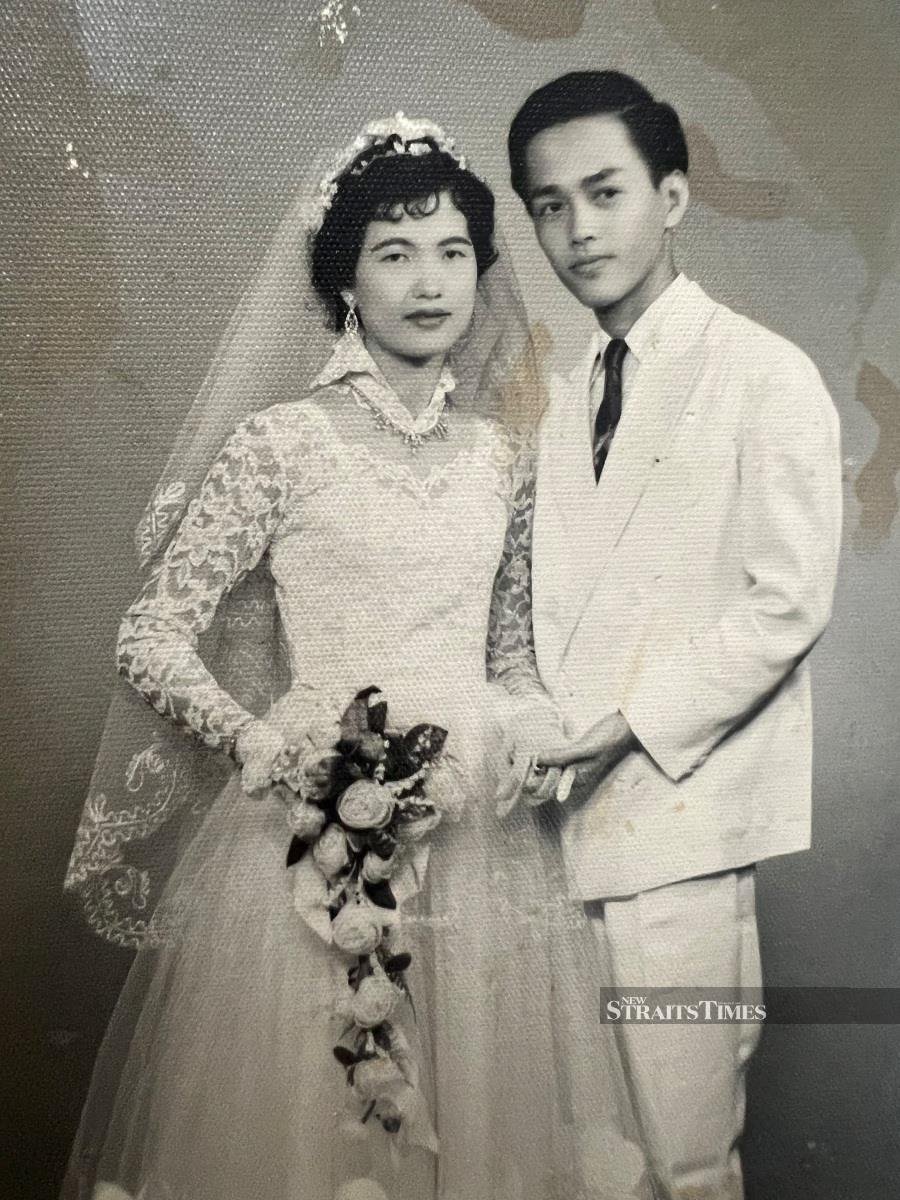

"Lu punya bapak masih ada (Is your father still around?)?" he asks suddenly. I shake my head. He nods stoically. Ng recently lost his wife of 63 years about three months ago. His face falls again.

He took on the role of a caregiver to his bedridden wife for two years. "Saya dua tahun tadak niaga (I haven't been doing business for two years)," he shares candidly, explaining: "Saya jaga bini. Bini saya sakit. (I was taking care of my wife who was ill)"

After she passed on, Ng decided to reopen his shop. "What else can I do?" he shrugs his shoulder, adding: "I needed to keep myself occupied and my sons encouraged me to come back to the restaurant." It's one way of keeping healthy, he confides, continuing: "I'm on my feet, I keep busy and I enjoy what I do!"

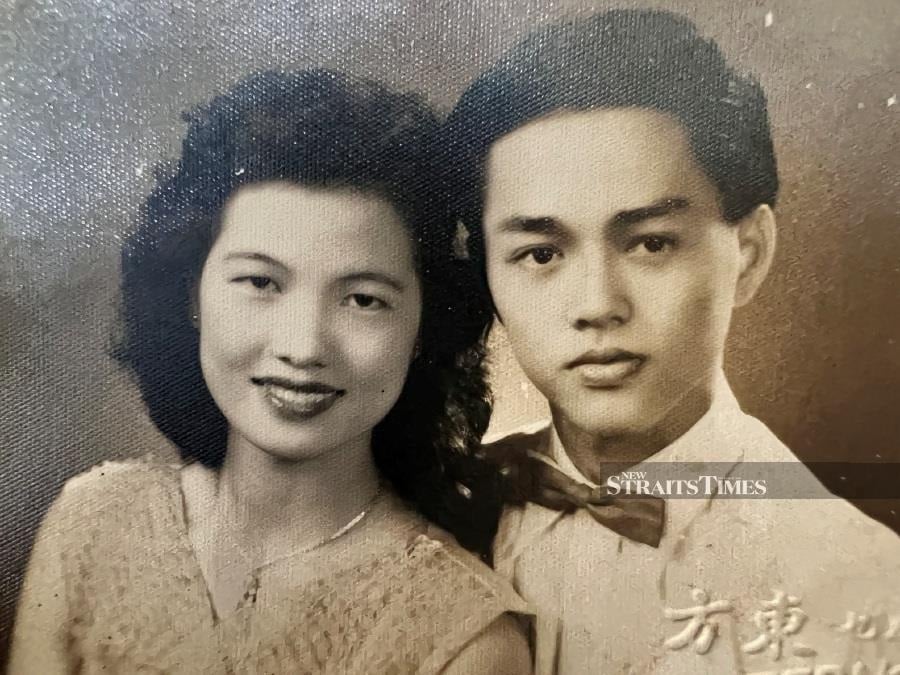

Life goes on, he adds stoically but his eyes glistens slightly. His wife had been a faithful companion for over six decades and it can't have been easy to navigate life without his childhood sweetheart, Yap Siew Loon. "She was my neighbour in Labis," he reveals simply with a slight smile, adding: "We grew up together."

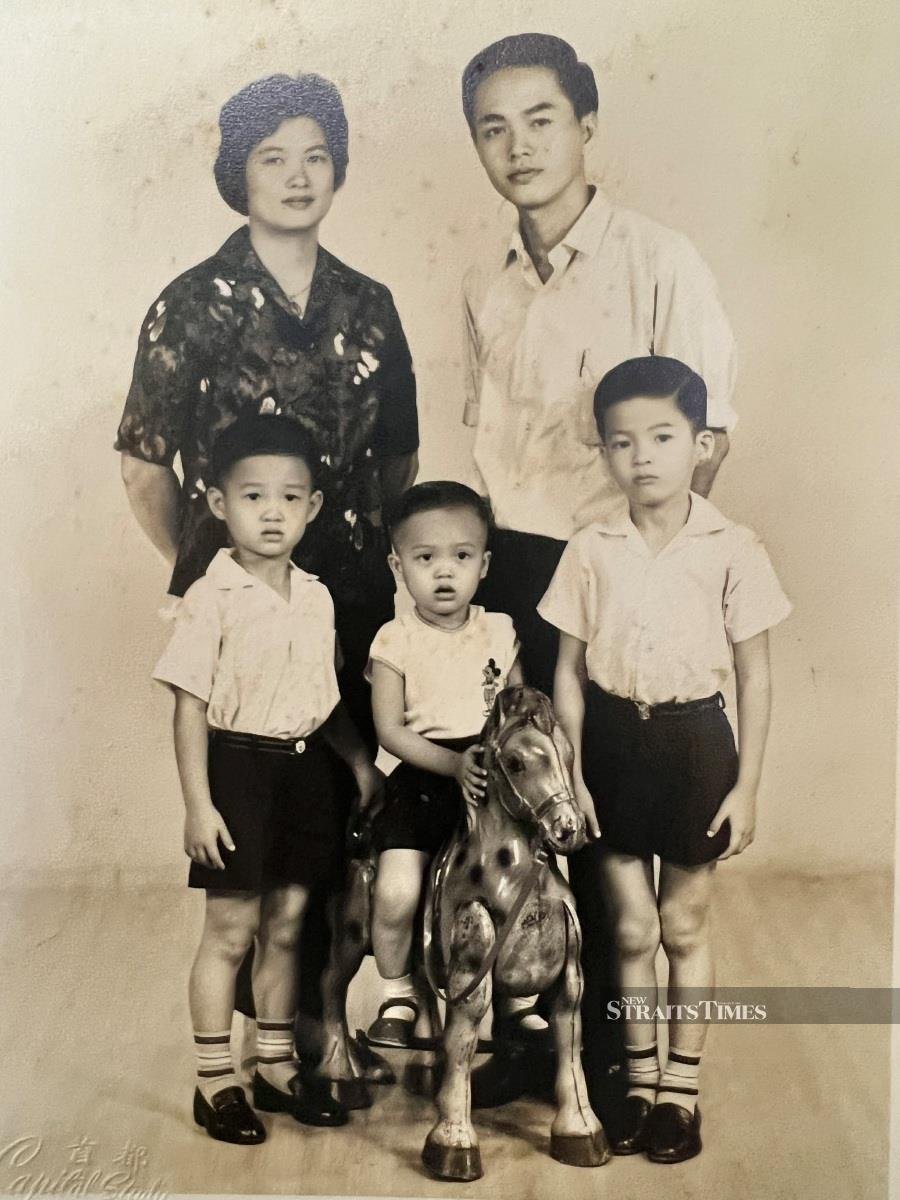

The eldest of nine siblings, Ng was born in Klang in 1939 to his immigrant parents who came to Malaysia from Yongchun, a county in China's Fujian province, to seek a better life.

"They did all sorts of businesses," he tells me bluntly. "Anything to eke a decent living and support the family." From running a coconut business in Tanjung Karang, Ng's parents moved to Labis, Johor where they helped in a confectionary business.

They were poor and Ng stopped his primary school education in Labis to help his parents at the confectionary business. "We'd wake up at 4 in the morning to prepare and pack up cakes to be delivered around the neighbourhood," he recalls. The enterprising boy also sold vegetables and helped rear pigs. "Back then, we weren't afraid of hard work," he muses, looking out in the distance.

Love blossomed with the girl next door and eventually Yap and Ng moved back to Klang, where they tied the knot and eventually raised a family. "I had nothing at all, but Siew Loon agreed to marry me anyway," he shares with a smile.

Ng took up a job at the Fung Keong Rubber Manufacturing Company, which produced the once ubiquitous Fung Keong rubber shoes. The rubber sole canvas shoes had massive appeal during those years of economic hardship due to its affordability and are permanently etched in the collective memory of those who grew up in the '60s.

"We rented a room and I had to take on several odd jobs to feed my family," he says with another shrug of his shoulder. Ng enjoyed cooking for his family and decided to open a food stall in Klang town at nights. "I worked at the factory from 8 in the morning to 5 in the evening, earning around RM2.80 a day. At nights, I sold char kuey teow in town."

A LEGACY

Business was good back then, says Ng. "There weren't many restaurants in Klang then. We had several food stalls and most people flocked to eat. Food was cheap then because the ingredients were plentiful and cheap."

It's different now, he says regretfully, adding again: "Everything's so expensive!" Ng eventually moved his stall to a vacant land in Melawis. "That was over 50 years ago!" he shares with pride. He later bought over the shop lot where he operates his business to this day.

The father of three sons doesn't intend to stop any time soon. "I enjoy what I do," he says with a smile, adding: "You have to have a heart for this business. Mesti ada hati. If not, you won't be able to last at all."

Someone's peering into the restaurant. Ng immediately jumps to his feet to greet the visitor. "Sorry, tutup hari ini (It's closed today)," he tells the person apologetically. He returns back with a regretful shake of his head. "I don't like disappointing people!" he says, sighing,

It shows in the way he conducts his business. Ng serves up each plate according to the customer's preference. "Some like theirs a little spicier, others don't want cockles… everyone has their own taste and I try to please everyone. My sons want to standardise everything but I do things differently. I remember each order although I don't write it down. I want everyone to enjoy their plate of kuey teow!"

I come early the next day. It's around 9:30am and the morning crowd at Ng's bustling shop is steadily thickening. The old man is already busy at the stove cooking up a storm.

He looks up and waves at me with a smile. "Go and sit down, I'll bring your order soon! Is there anything you can't eat? You can eat everything? Good! Go sit down!" The burst of chatter dies down as I sit down at an empty marble-top table.

Barely 10 minutes later, a plate of blackish, glistening kuey teow mee with its generous cockles and chee yau char (pork cracklings) arrive with a fried egg on the side. Some things haven't changed and I'm immediately transported back to the last time I sat in this shop with my father.

Dad sat back and watched me eat. He dug into his own plate and ate just as fast as I did. The wheelchair glistened in the late morning sun that filtered through the restaurant. We didn't talk much, but I could tell that my father was happy to be out of the house that he'd been confined in due to his prolonged illness.

If I close my eyes, I can still see silhouettes of my dad and me, leaning toward each other ever so slightly. I could see the glimmer in his eyes, and the half-smile that was a welcome change from his usual stoic expression. Most importantly, I could see the love between father and daughter in what ended up being our last good visit to the Melawis uncle's kuey teow shop.

Fathers, mothers, daughters, sons, grandchildren — they all come to Ng's little shop for a plate of hometown goodness with a lot of nostalgia thrown in. And the sprightly great-grandfather is happy to provide that little respite for his customers for as long as he can.

MELAWIS CHAR KUEY TEOW

Where: Jalan Lintang Gangsa, Taman Melawis, Klang, Selangor.

Business hours: Open from 9am to 3pm.

Closed on Sundays.