POWER has its terrible temptations. This is why parliaments try to pass laws that reflect the ethical standards of the people. But laws, being man-made, are susceptible to loopholes, which present "clever" politicians multiple escape routes.

Malaysia's anti-hopping law is one such. While we can't read the minds of the lawmakers, we can at least get a sense of what they were after when they passed the anti-hopping law in the shape of the Constitutional (Amendment) (No. 3) Act 2022, or Act A1663. It came into effect on Oct 5, 2022.

It may be safe to say that the lawmakers wanted the spirit of anti-hopping to be permanently lodged in the Federal Constitution. But intent and action sometimes don't march to the same drumbeat, as we are finding out now following the revocation of the membership of six Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia lawmakers.

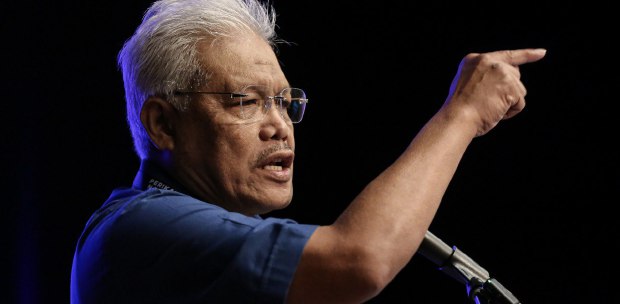

One of them, Mohd Azizi Abu Naim, a Member of Parliament for Gua Musang, Kelantan, was until recently an assemblyman for Nenggiri, Kelantan. He lost his seat after the Kelantan state assembly speaker declared it vacant. His legal bid to halt the polls in Nenggiri failed when the High Court dismissed his interim injunction on Thursday.

Will the fate of the ex-Bersatu MPs be the same as that of the former Nenggiri assemblyman? It's an easy question if we are after the spirit of the anti-hopping law, but made hard by the letter of the law.

Here, in simple English, is Article 49A of the Federal Constitution as far as it is relevant to the six MPs: an MP's seat shall become vacant if it is established by the speaker that the lawmaker resigned from or ceased to be a member of the political party. Resign, the six didn't.

Did they cease to be members of Bersatu when the party acted as it did? A chorus of voices given to reason will say revocation is equal to cessation. Not so quick, the law may say, drawing a distinction between revocation, some form of termination, and expulsion.

As a matter of fact, Act A1663 seems to treat "expulsion" as an exception in 49A (2)(c), which Bersatu seemed to have avoided by amending its constitution. Constitutional law columnist Charles C.J. Chow wonders why a loophole such as this was not spotted at the drafting stage.

A case of the spirit being willing, but the flesh being weak? To Chow, the cure has become worse than the malady.

We agree. There is yet another weakness in Act A1663.

It leaves the determination of the vacancy entirely to the discretion of the speaker. Chow wonders why the provision didn't ring a bell of trepidation among the lawmakers who passed it. We wonder, too.

Party-hopping, in whatever form, must not be allowed. It nullifies people's electoral mandate.

Voters, at least in Malaysia, elect parties, rarely individuals. Allowing "frogging", or worse, encouraging it, as Act A1663 seems to do, is to change the people's mandate.

Backdoor government is an old disease in this country, but this could be forgiven because there wasn't any anti-hopping law then.

Now that we have it, we must give the spirit of the anti-hopping law every opportunity to trump the letter of the law. After all, the spirit of the law is the intent behind the enactment.