It is somewhat strange that just as the country is witnessing our uniquely rotating monarchy again, seeing off a reigning king and welcoming a new one as it does every five years, Sarawak is also changing its head of state.

It is so because Sarawak's transition is not supposed to happen for another month.

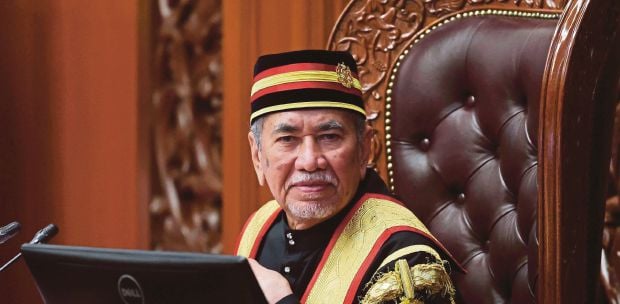

This has fuelled debate over whether Tun Abdul Taib Mahmud actually resigned a month before his third, two-year term as Yang di-Pertua Negeri is up.

The lack of an official explanation has unfortunately cast a cloud over Tun Dr Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar's appointment as the new Sarawak head of state.

That said, Taib's departure clearly marks the end of an era in Sarawak. His public career runs parallel to the state's entire history since Malaysia Day.

He was in Sarawak's first state cabinet and, given his legal training, played a larger political role than his ministerial portfolio suggested, including over land policies, which contributed to a constitutional crisis that saw the state's chief minister removed from office.

Taib then switched roles with his uncle, the late Tun Abdul Rahman Ya'kub, with former moving to the federal cabinet and the uncle became chief minister in 1970.

Intra-party tensions in the Sarawak coalition government under Rahman saw the return of Taib to the state, replacing his uncle as chief minister in 1981.

Taib was to remain continuously as Sarawak's leader for the next 33 years, surely a record hard to beat anywhere in the federation!

The 1980s were mostly consumed by the infamous uncle-nephew family feud, which came to a head in 1987 with the so-called Ming Court Hotel crisis, where a majority of the Sarawak Legislative Assembly members were corralled by Rahman's loyalists in the Kuala Lumpur hotel and called for Taib's resignation.

Instead, Taib called for a snap state election, the results of which were a nail-bitingly close thing, with Taib and his allies securing 28 of 48 seats contested.

But there was to be no looking back for Taib from then on. He was able to clean the house, consolidate his hold on power, and grow from strength to strength.

Two of those who rose to prominence after Ming Court were the late Tan Sri Adenan Satem and Tan Sri Abang Johari Openg, who went on to succeed Taib when he gave up office in 2014 to become the governor.

Whatever history's verdict on Taib, there is no question that his time in power saw a modicum of political calm, from which some economic progress was achieved.

But this is blighted by questions about favoured power brokers becoming exceedingly wealthy, best exemplified by the question about how a life-long public servant like himself came by the wealth he has amassed.

I tend to disagree with those who say that Taib's stewardship of Sarawak made it into a shining showcase of tolerance. He was an artful practitioner of political divide-and-rule tactics as any.

That the dominant ruling Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu only accepts the state's Bumiputeras as members shows that race-based politics in Sarawak is not much different from that prevalent in the rest of the country.

The final years of this durable political figure have been marked by ill health and squabbling within his family over the substantial inheritance he has bequeathed them.

For ordinary Sarawakians, it will be some redemption if there is some reckoning for some of the uneasy questions Taib's political stranglehold over their lives over so many decades has raised.

The better to avoid history repeating itself. Self-introspection may also be necessary in order for Sarawakians to avoid the easy and seductive temptation to lay most of their problems at the door of federal authorities.

* The writer views developments in the nation, region, and wider world from his vantage point in Kuching.