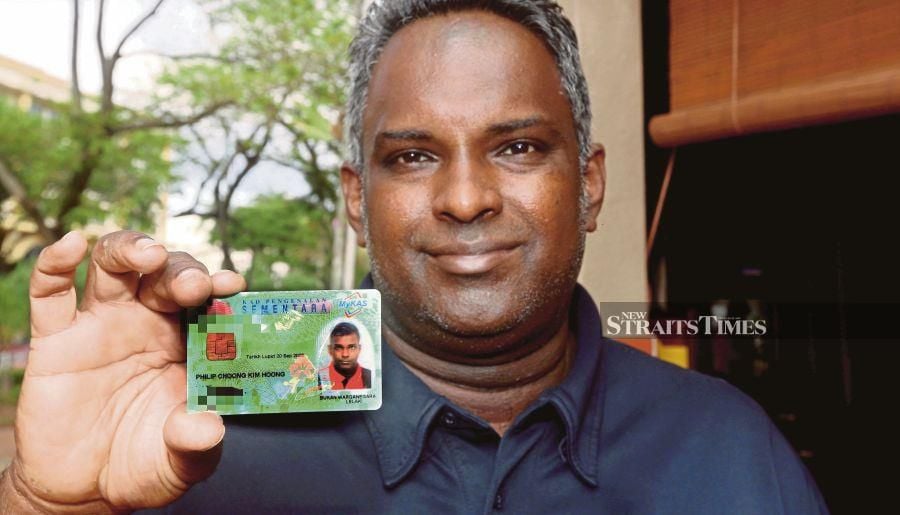

IPOH: Philip Choong, 41, was abandoned at birth.

He has been dreaming of travelling to Melbourne, Australia, to meet his friend and work with him.

Choong also wishes to travel to Hatyai, Thailand, to meet his girlfriend whom he has known for almost five years.

However, he can't apply for a passport as he does not possess an identity card or a MyKad.

Choong was adopted by a Chinese family who listed themselves as his birth parents on his birth certificate.

It is for this very reason that the National Registration Department (NRD) seized his birth certificate when he applied for an identification card (IC) at the age of 12.

Choong was given a replacement birth certificate without details of his adoptive parents.

He has since tried to apply for an IC but has been turned down countless times.

He works as a merchandiser but is unable to earn more compared with his colleagues as his employer thinks that he is not truly Malaysian.

Choong speaks fluent Bahasa Malaysia, Cantonese and English, but he has no pathway to citizenship.

"Despite being born to a Malaysian Indian mother, up until today, I still haven't received my MyKad.

"My application has been turned down for the umpteenth time.

"It is hard for me to open a bank account, apply for a passport or get a driving licence. And my salary is much lower compared with other Malaysians.

"I am a Malaysian but I feel like I have been left at the side of the road," he said, adding that his adoptive mother did not know the right procedure of adopting a child.

Choong said there were times when he blamed his adopted mother for everything that had happened to him but he was still grateful as he wouldn't know what would have happened if she had not adopted him.

He said his adoptive mother spotted him at the midwifery centre in Jalan Kampar a week after he was born and decided to bring him home.

"My biological mother probably didn't have any money to pay the adoption centre or had other issues and decided to leave me there," he said.

On the government's proposal to amend several provisions in the Constitution on citizenship matters, Choong said the power to amend it should not abrogate any of the people's fundamental rights.

"The government should prioritise the welfare of the citizens and non-citizens, including those currently stateless who have been living as Malaysians, considering Malaysia as their only home.

"The stateless people are already deprived of their rights to education, healthcare and so on. They will forever be stuck in Malaysia and be unable to do anything," he said.

Among the categories of stateless people in Malaysia are children born out of wedlock to a Malaysian father, stateless children adopted by Malaysian parents, abandoned children without documents to prove their nationality and families with generations of stateless children born in Malaysia. The NRD, too, has largely contributed to the growing number of stateless persons, he said.

"They (NRD officials) have given the wrong advice, directing the stateless individuals to the wrong type of application, adding unnecessary stipulations to applications contrary to the law," he said.

Malaysia is one of only two countries in the world, alongside Barbados, that restricts citizenship for children.

In Asia, Malaysia is among the countries with a large population of stateless persons, with over 16,000 reported in June last year.

The New Straits Times spoke to a few others who are also in their journey to being recognised as proud Malaysians.

CASE 1:

Siblings Tiara Natasha, 13, and Reshma Dewi, 12, were born out of wedlock to a Malaysian father and an Indonesian mother.

They had been using their birth certificates and approval letters issued by the NRD to enrol in a national school. The siblings said they had been anticipating the day that they would no longer be deemed as stateless children and recognised as Malaysians.

"I'm lucky as my friends accept me for who I am and my teachers are supportive of me.

"However, I do experience moments of doubt where I question my identity. Why don't I have an IC (MyKad) after turning 12," said Tiara when met recently.

Their father, V. Punithan, 57, adopted them as per the government's procedure in order for him to apply for their citizenship a few years ago.

CASE 2:

Muhammad Danish Haiqal Abdul Rahman, 10, was born at the Kuala Lumpur Hospital in 2019 and was adopted in the same year by Hazlina Hamzah, 49, from Petaling Jaya, after going through procedures at the Welfare Department.

However, he is a stateless child due to his mother's failure to be present at the NRD. His life has been affected by it in various aspects, including education and healthcare, and he is unable to lead a normal life.

Hazlina, who has no blood relation to either Danish's mother or father (both Malaysians) has submitted an application for his citizenship in accordance with Article 15(A) of the Constitution.

Under the existing law, the federal government may cause any person under 21 to be registered as a citizen in such special circumstances as it thinks fit. Last year, the government proposed lowering the age limit from 21 to 18 to obtain citizenship, among others. By Nuradzimmah Daim and Zahratulhayat Mat Arif