The Malay Nusantara garden demonstrates the community’s close relationship with nature, as well as its belief and culture, writes Ninotaziz

THROUGHOUT mankind’s history, we have been enticed by the promise of a heavenly garden, paradise itself. It is perhaps then quite natural for man to constantly try to emulate the idea of Eden. Senses come alive when caressed by the wind, stimulated by an ancient scent, and mesmerised by the gentle sway of a flower.

In the Hikayat, the most famous garden was that of the Taman Larangan in Kayangan. In the story of Mayang Sari, the mortal Awang begged the princess to take him to Kayangan so he could get to the enchanted bakawali flower to heal his mother’s ailment. In fact, the annual blossoming of the bakawali flower is often a magical moment. Deep in the night when the air is at its coolest, the delicate white fragile petals will gracefully open over a period of two to three hours and fade just in time for morning prayers.

Likewise in the mak yong story Dewa Muda, the prince searches for the princess Ratna Sari high and low to the bountiful Taman Larangan, where the fruits were so delightful and delicious, he simply could not resist tasting them, and was branded a thief for doing so. Meanwhile, in the Nek Kebayan’s garden there is always a clear stream running so that princesses can relax and play in its crystal clear waters.

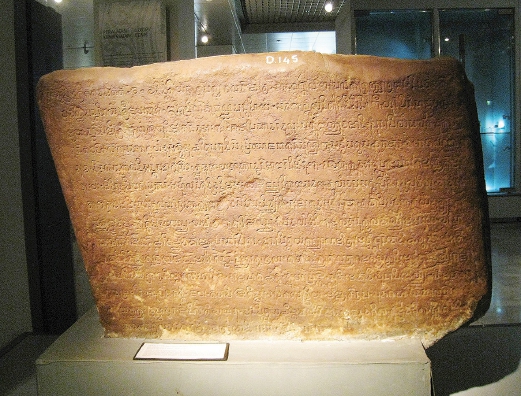

But the idea of Eden on earth is not only found in old legends and fairytales. The Talang Tuwo inscription describes the creation of a beautiful park by the Sri Vijayan king Sri Baginda Sri Jayanasa, who ruled in Palembang in the 7th century. The botanical garden called Sriksetra was described in detail. An excerpt from the inscription here in olden Malay is easily translated to Bahasa Melayu as we know it today.

nitanam di sini niyur pinang hanau rumviya dngan samicrana yang kayu nimakan vuahna

Talang Tuwo Inscription stone

(March 23 684)

The inscription reads: “May all planted here, coconut tree, Areca catechu, Arenga pinnata, sagoo, and all kinds of trees, the fruits are edible.” The good king went on to say may all other plants with the dams and ponds, and all of good deed that he gave can be enjoyed for the benefit of all creatures.

It’s certainly mindboggling to know that the Malay Nusantara garden has a history dating back 1,400 years. All this while my vision of the gardens have been those I imagined in the legends and lores I know of. With this discovery, I believe more than ever that our Hikayat are the memories of our ancient civilisation.

Our storytelling, the favourite pastime of the past, has many lessons to share. Through its study and that of the Malay Manuscripts, practices contained in the Malay world, in this instance, Malay garden, demonstrate our close relationship with nature, our belief and culture.

It is not only the idea of the garden that is depicted in these recollections from ancient past; it is a whole art of landscaping complete with garden features and nooks and corners to create the perfect sanctuary. For example, when we read Hikayat Hang Tuah, we find the description of a pond with lotuses and water lilies, and huge tanjung and kenanga trees providing shade by the pond. There are golden fishes swimming in it... In the middle of the pond there is a small manmade island made of white stone called Pulau Sangka Sembika.

...maka adalah dalam kolam itu pelbagai bunga-bungaan daripada kenanga dan teratai dan seroja dan bunga tanjung; dan ada dalam kolam beberapa ikan, warnanya seperti emas, dan pada sama tengah kolam itu sebuah kolam diturap dengan batu putih, bergelar Pulau Sangka Sembika.

An enchanting garden indeed.

There are many types of garden ornaments that survived the grandiose palace garden in today’s kampung. For the well-to-do, there are arches (gerbang), ponds (kolam) and wells (perigi). Not to mention a place to rest (pelantar) or the more formal gazebo (wakaf).

In the paddy field and other compound areas, you will find a small bridge (titi) or a resting plank (pangkin), chicken coop, (reban) and a shed, (bangsal). In many a kampung scene, during the preparation of meals, the young ones would be told to run downstairs to the garden to get lemongrass, lime, pandan leaves or other herbs before they disappear into the surrounding woods to play or go fruit picking.

During festivities such as Hari Raya or weddings, the garden becomes an extension of the lively kitchen. There are tempayans for capturing rain water and cooking areas to cook in the open. Fruit trees, herbs and flowers are in abundance. Bamboo crackling in the fire, and cooking lemang out in the open, is an example of how central the role of a Malay garden is in the Malay household. There would be wajik and dodol in huge kualis (metal pan). Meanwhile, in another corner there would be a steaming pot of hot water to cook the ketupat in stoves made of huge stones.

From the Malay palaces to the homes of the Malay people, elements of the garden mentioned above showcase our unique way of life. It’s one that should be treasured as it offers an invaluable insight into the use of every element in the garden and surrounding environment in daily life.

What would be really useful is to understand that the Malay garden is an innovation that we can export, a creation that we can enjoy and a concept and philosophy that we can learn from. More importantly, it is a heritage that we have inherited for more than a millennia.

Through this understanding of these pointers from our ancient past, the identity and image of Malay garden can be a source of reference for those among us who strive to promote the ideals of our Malay culture and heritage.

ninotaziz would like to thank Srikandi, author of the best-selling Baiduri Segala Permaisuri for the Talang Tuwo inscription quote.