THE strokes are bold and brash. Arresting in their various forms. It's simply impossible to steer my eyes away from the framed works of art lining the walls and along the floor of this impressive space belonging to Chinese calligrapher Jameson Yap, or JY, as he's better known.

Shelves heaving with all manner of books; an unusual collection of paint brushes hanging from their wooden stands; rolls of art paper stashed in nooks; collectibles dotting every available space… I feel as if I've stumbled into a private den — and shouldn't have.

"Welcome to my cave!" says the tall and handsome gentleman in front of me, his dark eyes gleaming with pride. Offering his hand in a warm handshake, he beckons me to take a seat by a big wooden table on one side of the room.

Yap, the artist famed for breaking the rules of a 2,000-year-old art form by putting a more modern stroke and reinterpreting it through an innovative and contemporary lens, is eager to share his aspirations for this ancient art.

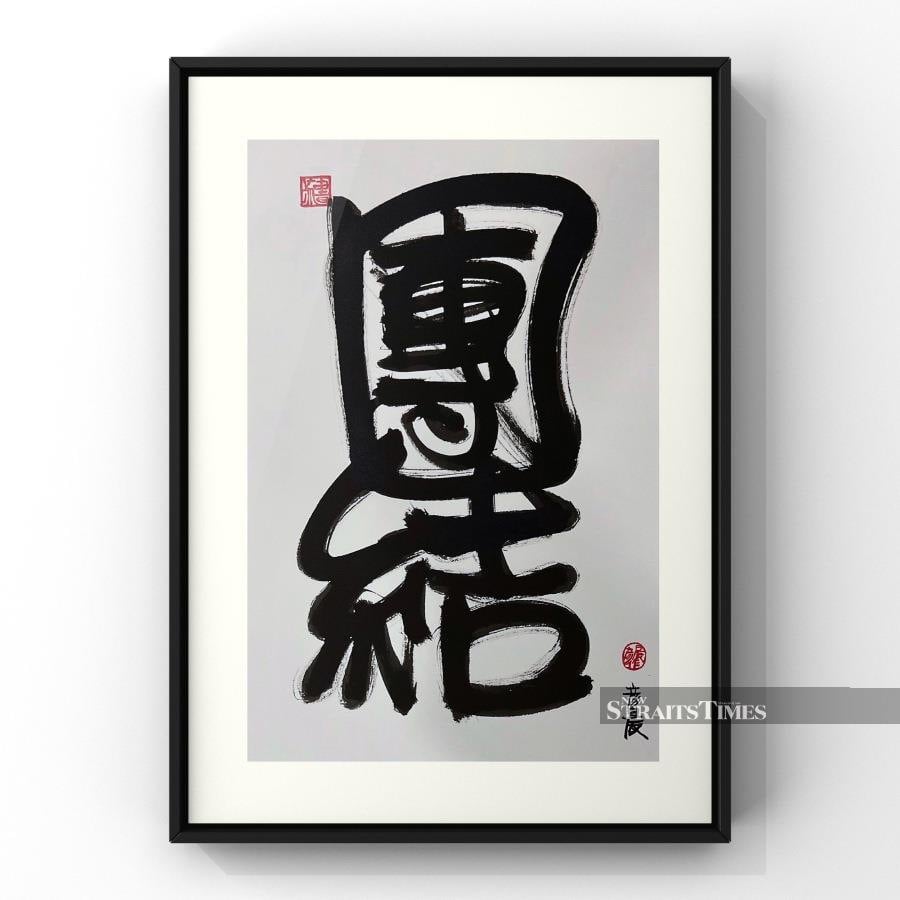

His main aim? To champion the art of Chinese calligraphy — the stylised artistic writing of Chinese characters, which combines visual art and the interpretation of the literary meaning — by making it relevant for today's audience and thus pushing it to the forefront.

FREEDOM OF REINTERPRETATION

From a very early period, calligraphy has been classified alongside poetry as a means of self-expression and cultivation — an outward assertion of one's inner psychology. But whilst its essence has remained the same, the relationship between calligraphy and abstraction has evolved through the decades.

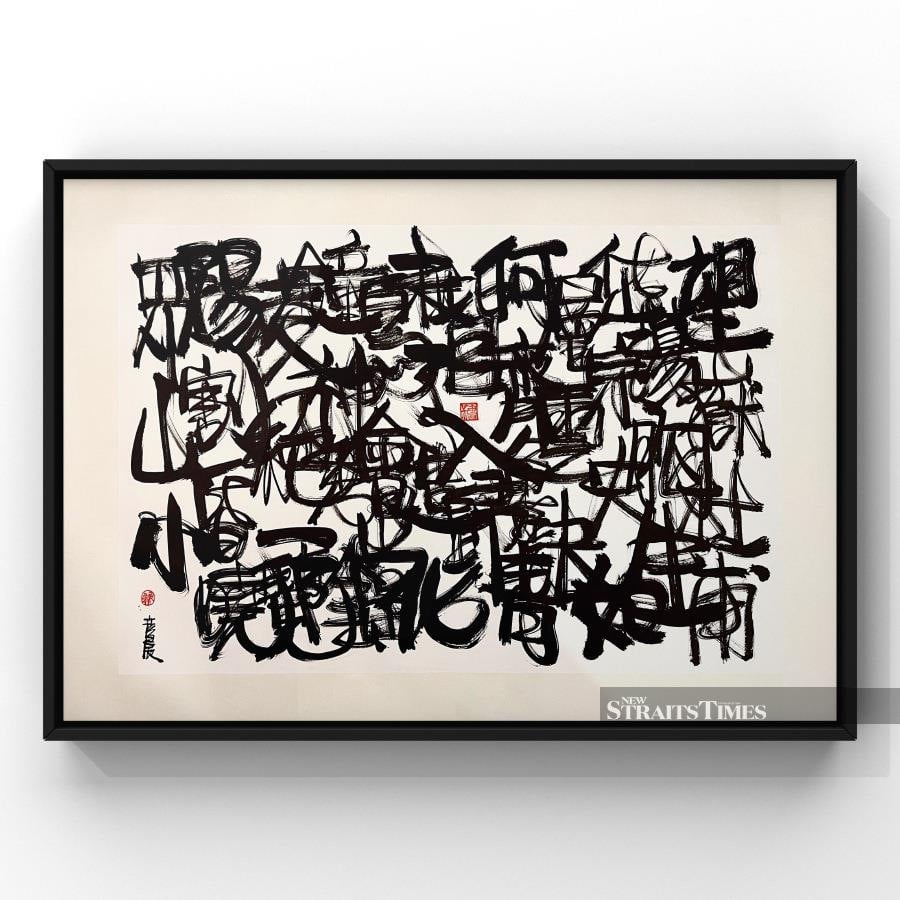

Forms, styles and techniques are no longer so rigid like before because artists have the freedom of reinterpretation. "I want to portray calligraphy as a creative, communicative and expressive art, rather than just focusing on the traditional style of writing," confesses Yap, adding that through his work, he's trying to express the style, influences and characteristics of a Malaysian growing up in Nanyang, China.

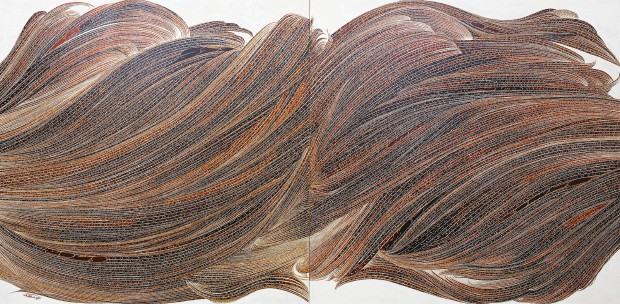

Unlike the structural methodologies and the emphasis on mastering the "perfect stroke" in traditional Chinese calligraphy, Yap likens his script to a river; where the characters can be completed in one single, continuous stroke, or as he puts it so poetically, "in a single breath".

Dubbed the River Stroke (Liu Su in Mandarin), each stroke is an ode to the depth and beauty of the flow of water in a river. Working on a blank Xuan paper, Yap utilises a single continuous brush stroke in a single breath. Here, form and structure merge to create works of art that spotlight the "chi" of the human spirit from a calligraphic point of view.

Of the overlaps in characters, Yap explains: "It offers the opportunity for people to revisit the piece. And every time they do so, they might see a different word entirely, but one that would resonate with them."

His River Stroke series is a collection of art work that's steeped in the ancient Chinese art, albeit re-imagined through a uniquely contemporary lens. It's a combination of tradition, culture, poetry and emotions that can be appreciated as an art form first, before delving into the meaning behind each character.

"It was my breakthrough moment when I created my signature style, the River Stroke," confides Yap, eyes lighting up. Adding, he says: "It's inspired by the movement of the Amazon River in South America, which I saw in a National Geographic documentary."

It was a bird's eye view of the Amazon River, a massive, intricate water system weaving through one of the most vital and complex ecosystems in the world, that captivated him so. Remembers Yap: "It's so powerful, agile, flexible and yet, so natural and gentle at the same time. That really resonated with me because it matched with what I'd been doing."

Being classically-trained himself, Yap is quick to refute the idea that he's dismissing the importance of the practice of perfecting one's strokes when it comes to Chinese calligraphy. "But I do believe there's more to calligraphy than just perfecting the strokes and making the characters look a certain way," he says, softly.

His late grandfather, confides Yap, would always emphasise that to be a good calligrapher, one needs to first understand the characters, and then its message, and finally capturing its energy when written. "Without character and soul, no one would be able to appreciate the art of calligraphy," surmises the earnest 41-year-old, thoughtfully.

When creating a character, Yap shares that he needs to study it (the character) deeply first and create some kind of story that can be connected to that character. "Sometimes, for a whole day or even the whole week, I'd have the character playing in my mind — like, say, the word 'gratitude' — and I'd be thinking of stories from life that can be connected to it. This process is important because this is how you get the energy to remain in that piece of work."

BIRTH OF A PASSION

He was only 5 when he started learning calligraphy. It was his grandfather who was responsible for nurturing his love for this ancient art, confides the Kangar-born artist. Rolling back the years, he shares: "I grew up in Perlis until Standard 6, and then I moved to Alor Star, Kedah."

Adding, Yap continues: "My father wanted me to be independent, so he threw me out of my comfort zone. From Alor Star, I went on to attend private school in Penang for Form 4 and 5. After that, I found myself in Kuala Lumpur pursuing my art studies."

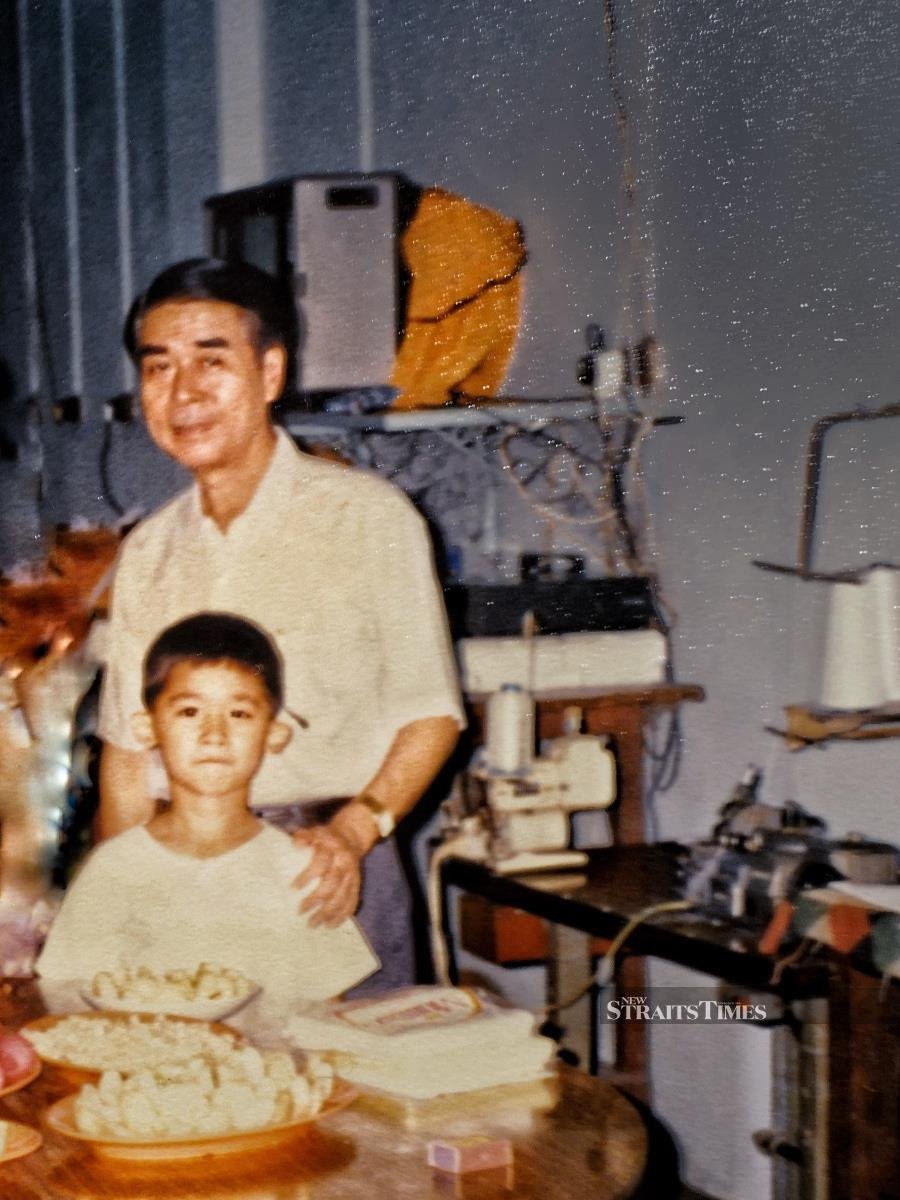

He remembers that his parents ran their own business when he was growing up. His grandfather, whom he spent most of his time with as a child, was a tailor. Smiling, Yap, the second of four siblings, points out: "Back then, tailors were like artists, too. They made and designed clothes from scratch. They had to be creative because they needed to know how to match the buttons and the colour of the zips. They had a good eye for detail."

His parents, recalls the soft-spoken Sagittarian, were not artistic in the least. And neither were any of his siblings. Chuckling suddenly, Yap muses: "From young, I was always artistic. Being the second child, I enjoyed a lot of freedom. My parents were strict in some ways, but they were busy working. So, I had a lot of free time. As long as I was home before dark, it was okay. After school, I'd usually cycle to the river and play there, or go to those abandoned construction places in Perlis."

His childhood, he remembers with a fond smile, was interesting. A leisurely idyll of play and learning. "I got to play with a lot of materials, like small mosaics. I could spend endless hours just engrossed in arranging these mosaics on the ground and then pushing them so they would fall in a line like dominoes. It was that freedom that enabled me to nurture my creativity."

Wryly, he confides that as his father and grandfather were in business, they both aspired for their young charge to follow in their footsteps. But Yap's heart was already set on becoming an artist.

"When I made the decision to go to LimKokWing University to pursue art, my father wasn't happy and we ended up not talking to each other for a while," confesses Yap, adding: "But I did very well and won lots of awards. By the time my father attended my graduation day, I think he finally forgave me. At least the money he spent for me to go to school wasn't wasted!"

REMEMBERING GRANDFATHER

Asked to recall his relationship with his grandfather, the man credited for introducing him to the joys of Chinese calligraphy, Yap's face breaks into a gentle smile. "Even though he's passed on, I can still feel his presence in this room. I don't have to see or touch him to prove that he's here. You know, sometimes even when a person is still alive and with us, we don't always spend time with them."

His late grandfather, shares the father-of-three, originally hailed from China. He migrated to a new country — Malaya — to start a new life sometime in the 1940s. Suddenly leaping to his feet from behind the table, Yap makes a beeline to a cabinet near the wall.

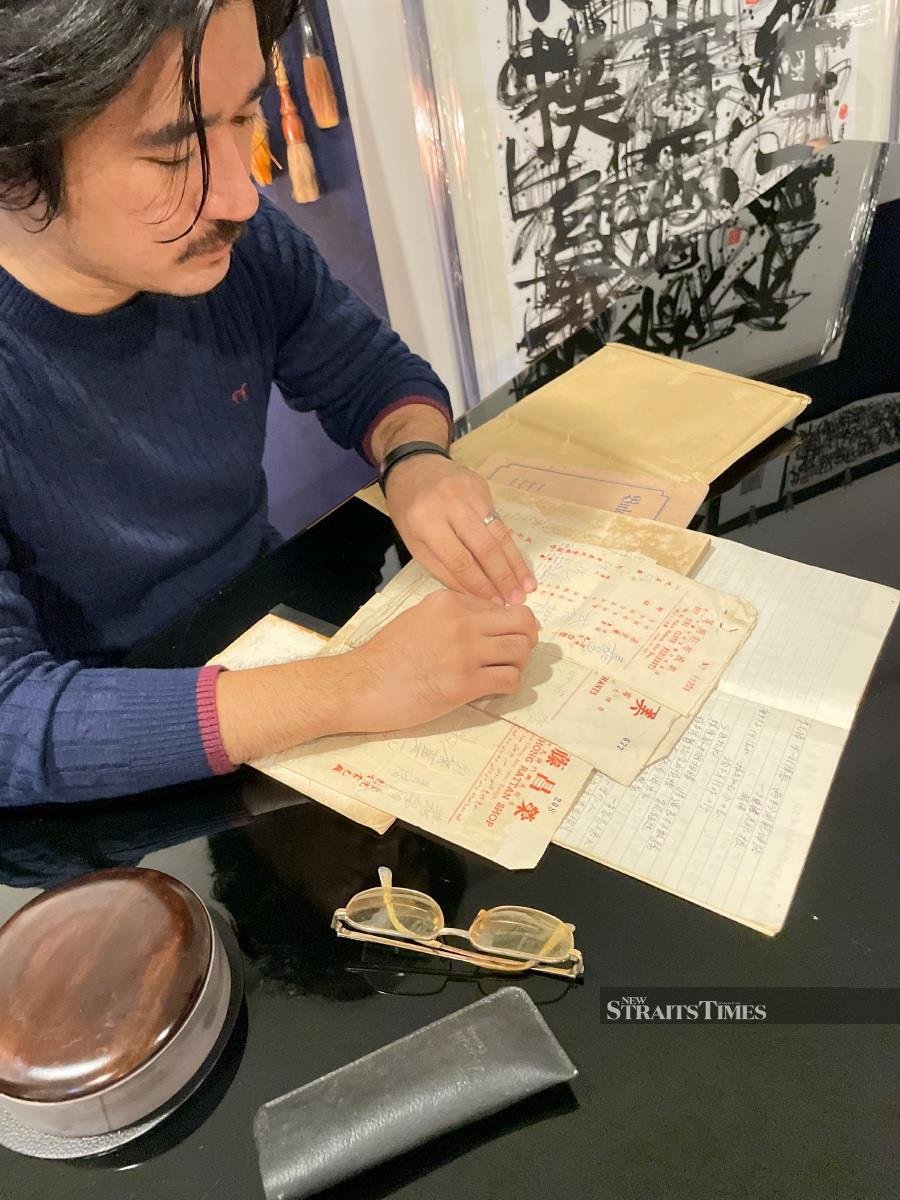

Returning with what appears to be a stack of journals or exercise books in his hands, he asks excitedly: "Can I show you something?" I nod enthusiastically in response. His eyes dance as he sits down again and gently begins to open a well-preserved exercise book, leafing through its pages with the utmost care.

"This journal and all these receipts and invoices here belonged to my grandfather," shares Yap, before proceeding to steer my attention to the words on the pages. "The handwriting is so neat," I couldn't help enthusing, and Yap beams in pride.

Smiling, he confides: "Grandfather loved to record his feelings and would talk to himself a lot. I guess he wasn't able to convey all these things to my grandmother. She was a generous and jolly person, but I don't think she was very romantic!"

His grandfather, adds Yap, was also a philosophical man. He liked to write about waves and compare it with life. "He used to say that life is like the waves, with its ebbs and flows, high tides and low tides," shares Yap, adding: "He would remind me to always remember the beautiful waves rather than dwell on the bad ones. He didn't write every day, but would pen things down whenever he was going through challenging times to motivate himself."

Slowly picking up a sheaf of papers, Yap scrutinises each one before saying: "When he started his tailor shop, he liked to keep all the invoices. He'd record every purchase and wrote down whatever was owed to him and by whom. But for him, it wasn't really about collecting the money; it made him feel good that he was able to help others. I remember he made a lot of donations to the primary school that I attended."

Grandfather, remembers Yap, was always generous with dispensing advice. Chuckling, the artist shares: "I was the only grandchild who had the patience to listen to him whenever he talked! He had a lot of good advice, but the one that continues to stick in my mind was this phrase: 'Fast is slow, and slow is fast'."

Noting my look of confusion, Yap attempts to elaborate: "It's relevant to art too. Like, when you're working on a piece and you're just wanting to complete it fast. So, you try to take short-cuts, but you'll realise that in trying to rush everything, you end up even slower because you start making mistakes."

Continuing, he says: "Slow can be fast. This means, when you put your heart into it and take your time with the process, what you create will be long-lasting. And this is what grandfather taught me. I don't know whether back then he just had all the time in the world or was far too free!"

Suffice it to say, his grandfather was a huge influence on Yap. "I'm not really a very detailed person when it comes to life. But with art? I am," he confesses, a small smile at the corner of his lips.

Leaning back into his chair, Yap, whose first job was with an advertising company where he was involved in commercial art, recalls that his grandfather made him practise his strokes and calligraphic sensibility all the time in his shop.

"I was given a stack of papers per day which I had to complete before I'd be allowed to go out and play," remembers Yap, adding softly: "He'd use a red pen to mark my work and circle the ones he considered good. This encouraged me a lot."

He enjoyed the discipline, admits the artist, before musing thoughtfully: "Having a breakthrough in art is good, but not blindly. I feel that the new artists these days are so preoccupied with having a breakthrough before they've even started."

Voice low, Yap elaborates: "It's important to go deep enough to understand your craft and know what there is to know… it makes better sense. I like the confidence of today's new artists, but sometimes it's overly confident and I don't think it would serve them well in the long run."

And he would know. Fast forward today, and Yap's 30 years of practice has led to the invention of his unique style of strokes, which, incidentally, he credits to his grandfather. "I can feel and connect with him during each process, which in turn gives me the confidence and affirmation to continue creating more artworks."

POWER OF NATURE

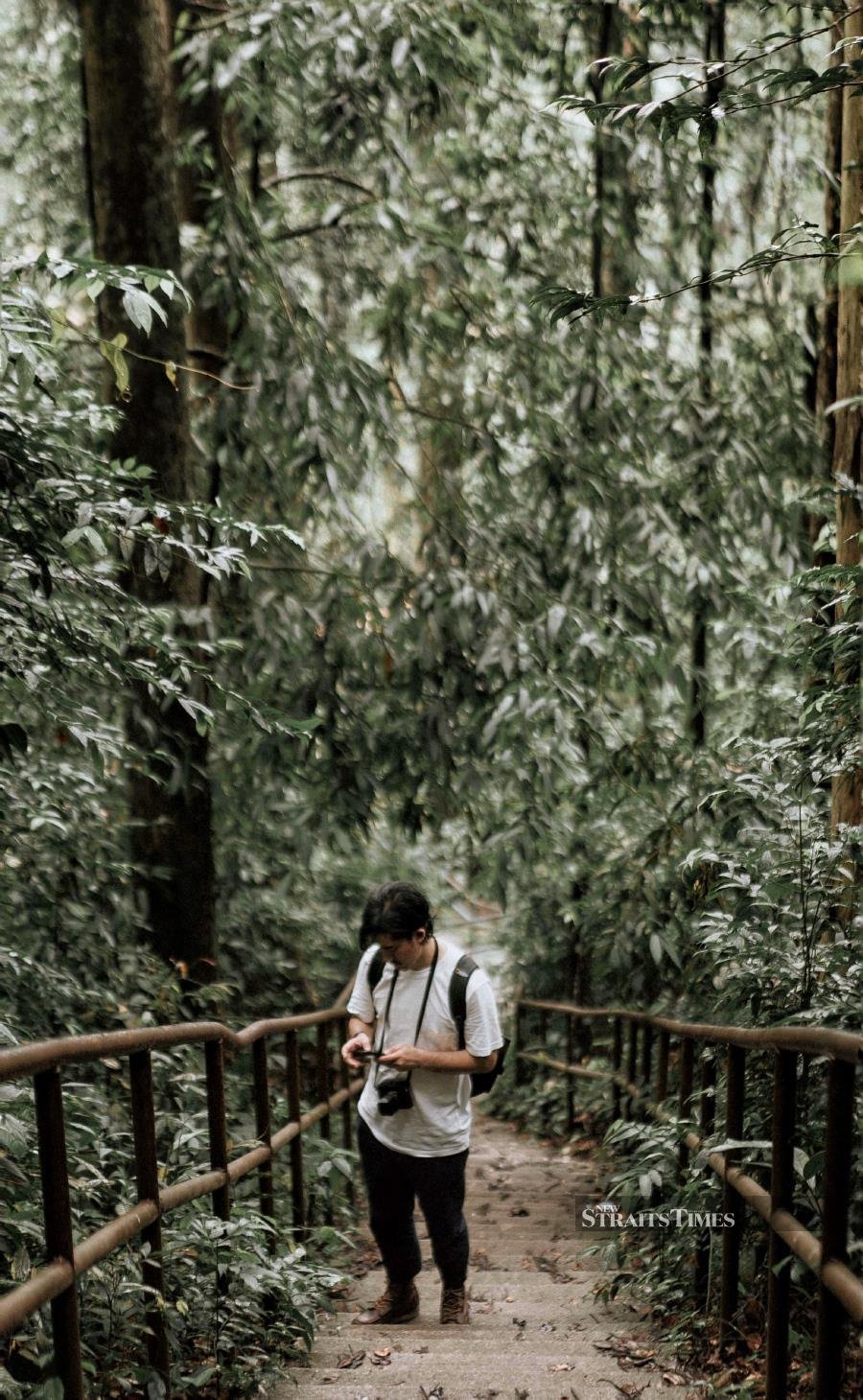

Yap, who held his first solo exhibition entitled "From TheArt" in October last year at Tsutaya Pavilion Bukit Jalil, derives his inspiration from nature. "I like to borrow nature's energy," he confides, simply, before elaborating: "Whenever I get the chance, I go into nature, armed with my brushes, to get the energy. There are a few places near Rawang where I like to hike and just do my stuff."

Looking thoughtful, he continues: "The water for my ink is from mountain water, which I collect in my bottles whenever I go. I even wash my brushes in the river water. And whilst I'm waiting for inspiration to hit, they'd (the brushes) be left to dry under the sun. I guess, at the end of the day, it's all about real emotion. I borrow nature's power. You can't do shortcuts. This is important for my art."

Energy, shares Yap, can be derived from emotion. "It's when you're touched by what you see or feel. Or maybe when certain words hit you with a particular impact. If you're calm enough to have that clarity, you'll notice that all these are the ingredients to my art."

With pride lacing his voice, Yap shares: "My customers who purchase my work always tell me that the energy on my canvas stays. This is because I'm able to translate onto my canvas real emotions, real energy and, of course, my skills."

Asked how we can find our own unique style, Yap pauses to ponder the question. Then, with a shrug of his shoulders, he replies: "It took me a while to find mine and then I finally realised it's about pure honesty towards yourself and your feelings. Look within instead of always putting your focus and energy on the outside world."

CONTINUING THE JOURNEY

A deafening sound pierces the calm in the room. It's the sound of thunder, an ominous sign of an impending downpour. Grimacing, I signal to Yap that I may need to wrap up soon before I get caught in a manic Friday evening jam.

He nods understandingly. What's your end goal, I quickly ask the artist, at the same time gathering my bits and pieces, which had hitherto been strewn on the table. A brief silence ensues as another "boom" from somewhere outside resounds again.

"End goal?" Yap repeats my question, and I nod earnestly. "I want River Stroke to become a 'teaching', a philosophy of life, if you like," he replies, adding: "And of course, I want to show the world that Chinese calligraphy is not a dying art. It's a traditional form of art that goes beyond the boundaries of race, language, culture and so on."

Smiling wryly, Yap points out: "There's a perception that you need to know Chinese calligraphy in order to appreciate it. That's not true. You can see from my work; even if you were to have just a tiny bit of connection, it's enough. It proves that art transcends. Just connect and feel."

Go to www.jycalligraphy.com for more info.