HERE’S a hypothetical scenario: One day, you are walking on a backlane in Kuala Lumpur and stumble on a strange device.

The object has been pried open, with white powder scattered all over the place. Without a second thought, you step over the powder and head home.

That night, you switch on the television and learn from the news that a “lost” radioactive container has been found in the alley, and the contents have been exposed.

Adding to anxiety, you notice that your shoes are emitting a faint blueish light! So, what are you going to do?

According to Professor Dr Ng Kwan Hoong, a radiation protection expert in Universiti Malaya, many Malaysians may not be aware of the grave situation.

While people fear anything that bears the “skull and crossbones” label, he believes not many can recognise the danger contained within canisters bearing the “three-bladed fan”, or trefoil symbol.

Unlike the recent chemical dumping in Pasir Gudang, Johor, where almost 6,000 people were sickened by toxic fumes, he said radiation exposure cannot be felt or detected until it is too late.

Even then, it’s interesting to know if community doctors could recognise the symptoms.

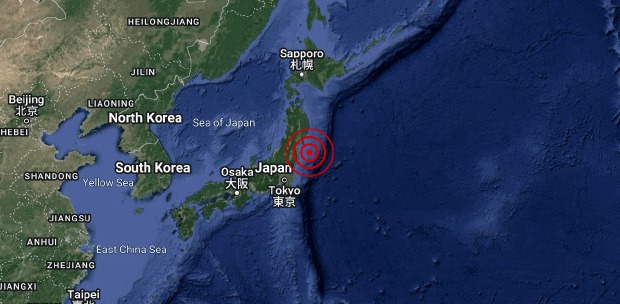

Ng, a corresponding member of the International Commission on Radiological Protection, had studied the handling of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2013, when he was invited to join a comprehensive research under the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“In Malaysia, the problem is that people are not educated about radiation like in Japan,” he said.

“What we should do now is to not wait for an accident to happen. We have to educate people as soon as possible. Look at the Japanese newspapers. Some of them publish daily background radiation readings after the disaster just like the weather report.”

The cost of a nuclear disaster, or even an accident, can be devastating.

When the Fukushima reactors failed, all land within 20km of the plant — encompassing an area of about 600 sq km and an additional 200 sq km located northwest — became unsuitable for human habitation.

Residents lost their properties overnight when their homes were declared to be inside the permanent “exclusion” zone.

The economy was affected when traces of radioactivity began appearing in food and in marine products caught in the Pacific Ocean.

However, Ng agrees that the Fukushima disaster is not what Malaysia should be worried about, but rather, it would be the likes of the 1987 Goiania accident in Brazil and, closer to home, the 2000 Somut Prakan accident in Thailand.

All involved radioactive devices inadvertently ending up in scrapyards due to oversight, causing mass contamination of properties, exposure of thousands to dangerous levels of radiation, and painful death to unfortunate victims.

In fact, the loss of an Iridium-192 container last August should set alarm bells ringing because, according to Ng, that was not the first and only device to go missing in this country.

And until today, its whereabouts are still unknown.

He said the Atomic Energy Licensing Act 1984 is sufficient to govern the use of radioactive substances and nuclear activities, but there is room for improvement in terms of creating awareness and holding people accountable As a proponent of radiation safety, Ng believes in its judicious use to benefit mankind.

Therefore, risk communication, which is his area of expertise, is a vital tool in educating people on what is dangerous and what is not.

However, perception seems to be the biggest enemy because fear generates anxiety that, in turn, gives rise to anger and violence.

In his lectures, Ng shows how newspapers termed the effects of the Fukushima disaster — “deadly radiation”.

While it’s true that radiation leaks may be fatal, but that doesn’t mean the whole of Japan had turned deadly.

To counter this, he outlines two notable observations. First, he said, was the impressive manner on how the Japanese handled the aftermath. All parties, including the nuclear plant operator, recognised their weaknesses and quickly took action to rectify them.

The government initiated a “Revitalisation” policy to rehabilitate the land.

It was not only about constructing new buildings or bringing more developments to areas near the exclusion zone, but also rebuilding the social structure that existed before the disaster.

To reassure people on the safety of their homes, simple detectors were provided so residents could monitor the radiation level in their surroundings.

Decontamination efforts were beefed up, with radioactive debris and topsoil being meticulously dug up for proper disposal.

Unlike the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown, where details were suppressed by the Soviet government, a transparent communication system has been set up to relay fast and accurate information.

“In Japan, they have sampling stations everywhere with thousands of radiation detectors to provide detailed real-time readings and maps.”

He cites websites like http://safecast.org and https://radioactivity.nsr.go.jp, which he describes as a fantastic demonstration of citizen science.

Second is to be prepared for the unexpected because human psychology is unpredictable.

Ng said he personally saw a rush to buy salt in Hong Kong just after the Fukushima disaster, which was sparked by an online rumour to ward off the effects of radioactive iodine.

Back home in 2011, Ng used to serve in the consultative committee on the analysis of public review of Lynas documents just before the company began operations a year later.

Sharing a bit on his work then, Ng believes that environmental sampling should be done frequently on a wider area.

The data should be publicised to reassure not only the people of Kuantan, but the whole country.

It is a bid to uphold environmental justice, where there is fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people with respect to development and implementation of environmental policies.

This way, he said, all segments of society will share responsibility for their actions, instead of one taking advantage and another is left to bear the consequences.

“Environmental justice covers many aspects of our life. For example, in terms of conservation, our earth has a finite resource of clean water, minerals and fuel. For centuries, humans have been exploiting these resources.

“So the question we want to ask ourselves is, if we carry on with our selfish, mindless exploitation of our precious resources, what justice do we leave behind for our future generations?

“To me, the ultimate purpose of risk communication is to enable people to make informed decisions to protect themselves and their loved ones.

“Some people say it may create unnecessary fear, but we’ll have to confront the matter to be prepared,” said Ng.