Finding the right ingredients in the wild was first step in brewing the delectable Zisun tea. Cheng Yuezhu reports

THE Classic of Tea, written by the Tang Dynasty (618-907) tea expert Lu Yu, rates a tea not made from green leaves as superior. The leaves in question were purple and shaped like bamboo shoots.

They still exist and are known as Zisun (purple bamboo shoots) and grow primarily in the mountains of Changxing county, Huzhou, Zhejiang province, where the Tang Dynasty Imperial Tea Factory harvested them exclusively for emperors.

Unsurprisingly, they are elusive and precious. Only 4 kilogrammes of purple tea leaves can be harvested from a plantation of about 1 hectare, said Zheng Funian, a national-level representative inheritor of the Zisun tea-making technique.

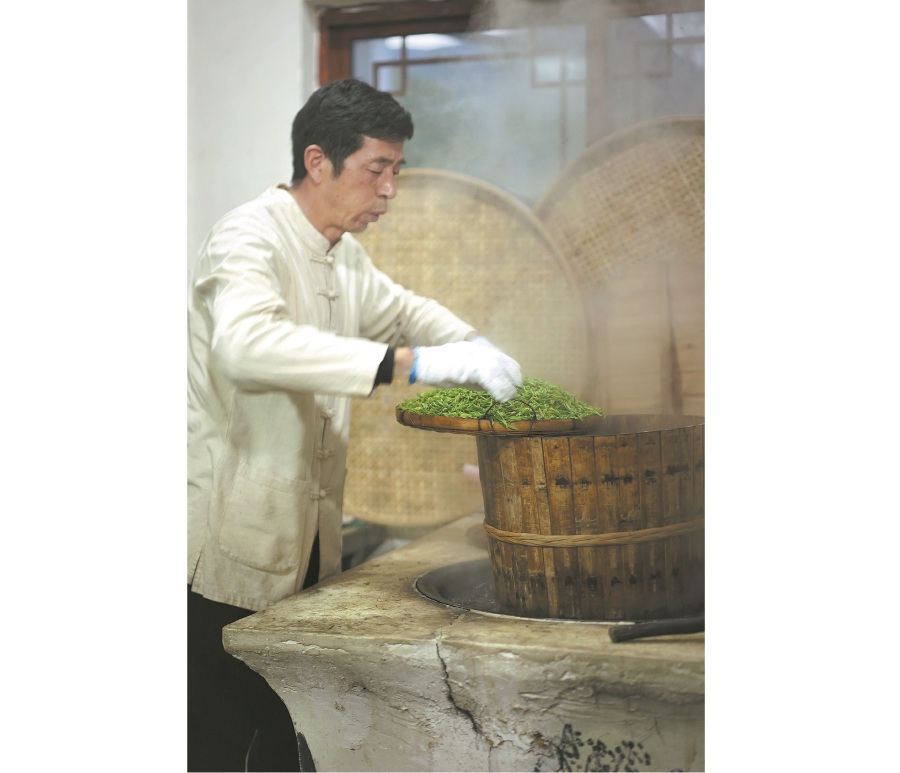

During harvest season each year, Zheng, 62, goes up into the hills in the early morning to pick the curly purple leaves that grow at the tips of tea plants and later spends hours roasting them.

When he was growing up near Guzhu Hill, the original site of the imperial tea factory, families used to pick tea growing wild on the hills before roasting it and drinking it, he said.

When he was 17 his parents started to teach him how to process tea and, eventually, it became his full-time occupation.

"When it comes to roasting, both talent and patience are needed," he said. "You have to be able to sit and endure hardship. I have a short temper, but sitting in front of a wok or a stove calms me."

Believing that tea can "embody the tea maker's soul", he has always processed the leaves by hand, rather than by machine.

Novices almost inevitably burn their hands, and Zheng was no exception. Most of his fingers were blistered until he gradually mastered the roasting process and managed to avoid burning himself.

"The most challenging part is feeling the temperature of the wok with one's hands. This is a whole system: shaking, gripping and tossing the leaves; it's almost like practising tai chi."

The local government has recruited tea experts to revive the Zisun tea processing technique, which for centuries was preserved only in texts, and Zheng began experimenting in the 2000s, restoring and improving traditional methods.

"Restoring the ancient processing methods is essential, but personally I got involved simply because I love tea and I like to try my hand at processing any kind."

He first searched for the purple leaves in the wild, roaming the hills with a bamboo basket and a hoe. Whenever he discovered a plant with the right leaves he would dig it up and replant it in his own plantation. Despite these endeavours, he managed to find only 80 or so bushes.

It took Zheng eight years to find enough plants and research ancient texts, including The Classic of Tea, before he could produce the compressed tea, all the while tweaking the traditional steaming-and-deoxidising process.

In 2017 he was made a national-level inheritor of Zisun tea processing, and last year traditional tea processing techniques and associated social practices in China were inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, with Zisun tea included.

Now, apart from growing and processing tea and refining his technique, Zheng teaches students about tea at schools, and teaches his apprentices his skills.

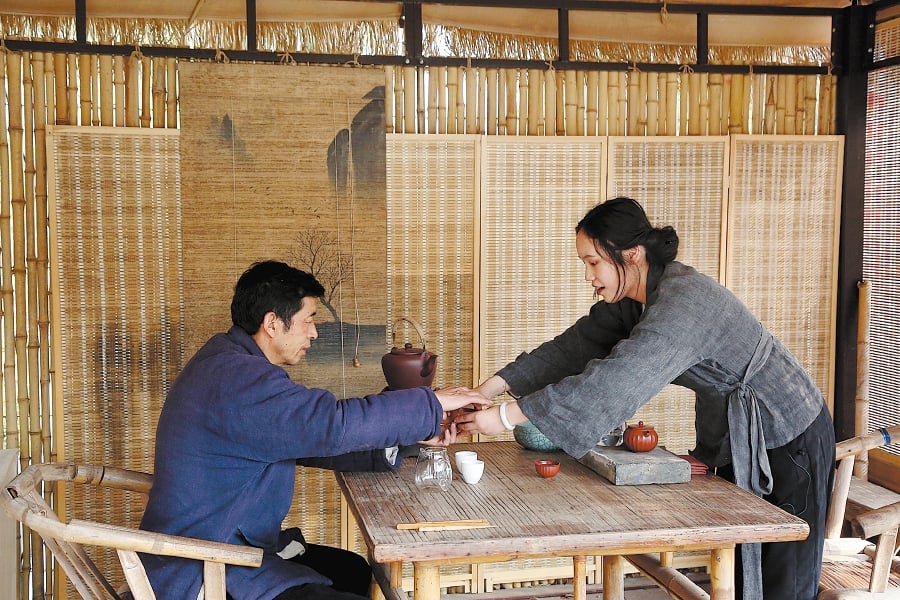

Among his 11 apprentices, Liang Xinye, 22, is both the newest and the youngest. Still pursuing a law degree at Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, she was officially apprenticed in March.

"When I was young I wasn't interested in learning the piano or dancing," Liang said. "Then a guest gave my family a tea set, and I played with it every day. No one in my family knew much about tea, so my mother found a tea sommelier to teach me."

At university she is head of a student tea culture society. It has about 200 members, and about 10,000 students have taken part in its activities, from lectures given by tea experts to field trips to plantations, she said.

Last year Liang took society members on a field trip to Changxing and met Zheng. Early this spring she spent a month on his plantation, getting up in the early morning to pick leaves and spending the afternoons roasting them.

After she completes her undergraduate studies next year, she said, she plans to continue learning processing with Zheng, and to learn tea theory.