Malaysia wants to be the next "bric" in the fast growing intergovernmental bloc of the South, BRICS, a name derived from the first five members of the informal organisation: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

A good choice, we must say. Here is why. First, the South's voice has been unheard for the longest time. BRICS may just be the "mike" to make itself heard, if not obeyed.

Many in the North think the grouping is a challenge to the West. Wrong, we say. BRICS is making the South's stand against Western hegemony and not challenging the West. There is a distinction with a difference here that many analysts miss.

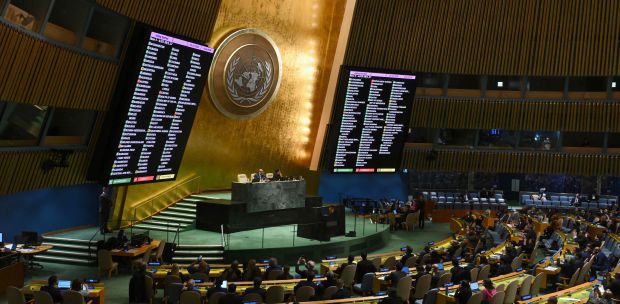

All these nations want is to be given a fair hearing on the world stage. The current world body — the United Nations— is a place where the voice of the South is repeatedly drowned.

Take Malaysia, for example. For the last 78 sessions of the UN General Assembly, Malaysian prime ministers had taken to the podium pleading for the just treatment of all nations whether they be meek or mighty. Seventy-eight years have passed and yet justice remains undelivered.

One prime minister was even labelled, unjustly it must be said, as recalcitrant for championing the cause of the disregaded nations. Nations and their leaders mustn't be crowded out like this.

Second, the current world order — if it can be called it — doesn't reflect the number of nations in the Westphalian world of sov-ereign countries. The last we counted there were 198, but five veto-wielding permanent members (P5) of the UN Security Council — the only law-making entity of the world body — rule and reign over the rest.

In any geopolitical text, this will be tagged tyranny by the few. The first move to reform the UNSC is almost as old as the UNSC. But because it is not in the interest of the P5 to enlarge the permanent membership or for them to give up the veto, reform of the UNSC is an impossibility.

Third, the financing of development in the South. BRICS has set up the New Development Bank to do exactly that. The NDB is promising in that it does not impose the crippling conditionality of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank when dishing out its loans, especially to the nations of the South.

What is worse, they have both been criticised for being gatekeepers of "power". True or not, transparency isn't a strong point of the IMF or the World Bank. The NDB must learn from this.

But BRICS is not the metaphorical yellow brick road. Challenges are plenty. One is the nature of the grouping. It is informal and decisions are driven by consensus. This may be more of a problem than an opportunity.

It should learn from the consensus-paralysed Asean, the 10-member Southeast Asian bloc. It is so hard to get the 10 members to agree on anything critical that nothing much happens in the region.

Two, three members of BRICS are big powers. They must not do what the permanent five of the UNSC are doing: imposing their will on the rest. If this happens, there will be no difference between the devil UNSC is and the deep blue sea that BRICS may become.