Arguably, we live in a moment obsessed with history. Issues of the day are pregnant with the past. Why history matters? Or does it even matter at all?

We are often reminded that "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it". Global and national leaders, including Malaysian prime ministers, have often used the phrase.

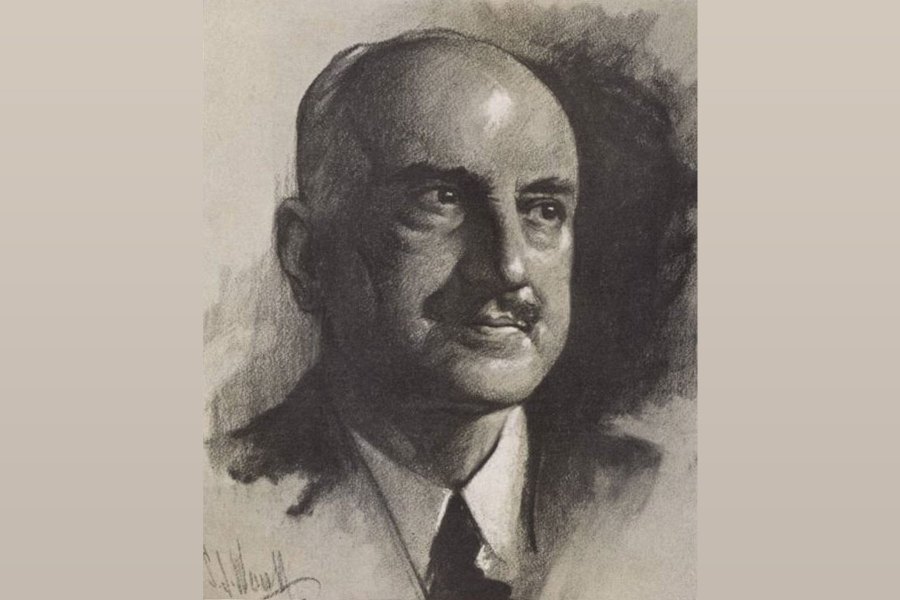

That reminder was written in 1905 by Spanish-American philosopher, George Santayana. (1863-1952) in his work The Life of Reason (1905). Born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, Santayana was a critic of Western civilisation.

Two rival interpretations of Santayana have prevailed since his death.

One view is that he was an elegant but elusive thinker, notable for his writings on topics such as the nature of beauty or religion, but devoid of any overall theme of continuing relevance.

Another is the more hostile one; that Santayana was a thinker who has simply ceased to speak to our age at all.

Santayana's concern was with the emergence of an industrial civilisation. He was disenchanted with the incomprehensive intellectual debris when the West was cut off from her classical roots.

Like the mood in autumn, or the "impending winter" as exclaimed by my University of Minnesota political science professor one morning to his dull-looking class in late October of 1983, Santayana's West was gloomy.

The modern world then was moving even deeper into the wasteland. Perhaps resonating with Elliot's poem, The Waste Land (published in 1922), Santayana links philosophy with poetry. In his words, it is the substance of the philosophic vision.

Santayana avoids the cold temperament of the climate that "regulates" European thought and philosophy.

The man who stated that: "The function of history… is not to reproduce its subject-matter", (1916) was born in Madrid in 1863. His parents were middle class.

He distinguished himself at Harvard College, graduating in 1886. And he was appointed to the Harvard philosophy department in 1889.

In 1912, he suddenly gave up his professorship to live and travel at leisure in Europe. He never married, remarking in his autobiography that: "I am a born cleric, or poet" (Persons and Places, 1944). That was his autobiography's first volume.

In the book series Thinkers of our Time, Noel O'Sullivan's Santayana (1992) suggests that the unifying theme of the philosopher's thought is "the search for a philosophy of modesty appropriate to what is now fashionable to call it as the 'post-modern condition'".

Santayana was an extraordinarily prolific writer who explored the human condition through poetry and poetic drama, literary criticism, autobiography and essays. He constructed an ambitious philosophic system.

His corpus is multi-faceted. O'Sullivan's intention is to awaken interest in Santayana's writings, and to renew the interest for those who already know him.

What then is the nature of Santayana's philosophy? There are two dimensions. One is formal. Narrowly conceived, it is an investigation into truth.

His major works are rigorous attempts to deal with the logical, metaphysical and epistemological problems that this formal dimension of philosophy entails.

The second dimension, according to O'Sullivan, is vision. This sees Santayana linking philosophy to poetry.

In Three Philosophical Poets (1956), Santayana says that the substance of the philosophic vision "is sublime…The order it reveals in the world is something beautiful, tragic, sympathetic to the mind or just what every poet, on a small or on a large scale, is always trying to catch".

And that is vision; and vision is insight. It assumes the transvaluation of values.

What Santayana means is that human reason has the power to shape history in accordance with whatever ideals the imagination may suggest. He terms it as "directed imagination". This happens in all nations and is not peculiar to liberal societies.

Santayana sees that the presentation of politics and history as a sphere that sets the stage for the occupation of "little designs and desires". This is the sphere in which all ideas, principles, -isms and disembodied values contend, not the interest of the man in the street.

In Domination and Powers (1951), he words this as the political sphere where "the new minister is again a child… He dreams of speeches applauded, measures passed, elections won…" Or similarly a new (revised) version of history texts? Would this be the past of our modernity?

What Santayana means on not remembering the past is not so much to change the human condition; but to make progress. The rest, is history.

The writer is professor of social and intellectual history, International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation, International Islamic University Malaysia