In late 2001, the United States launched a worldwide offensive campaign against terrorism as a reaction to the 9/11 attacks.

The Global War on Terror not only targeted the terrorist organisation but also any country that was deemed a terrorist haven by the White House.

The Taliban in Afghanistan were overthrown for its part in harbouring Osama Bin Laden, once an ally to the White House-turned-public enemy No. 1.

After the US invasion, the Taliban became a small group of tribal militias scattered all over the country rather than a potent political force as they used to be in Afghanistan.

Twenty years later, the Taliban swept back to power, leaving the US in great humiliation since the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975.

The fall of Kabul signifies the failure of the US's incongruent foreign policy, which cost the taxpayers about US$2 trillion for the two-decade war.

There were internal and external factors that could illuminate a formidable explanation of why the Taliban effectively swept through Afghanistan in less than a month.

Nonetheless, to what extent the victory of the Taliban could reinvigorate religious radicalism in Malaysia?

To put religious radicalism into context, one should examine the causal effect of the world geopolitical events that inspired the resurgence of radical Islamic movements in the past four decades.

The first wave was the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Determined to emulate the success back home, there was an upsurge of interest in Islamic political discourse among the youth. Since then, the discourse on secular governance versus Islamic governance has become a bone of contention between parties.

Unfortunately, the interest went beyond academic polemics. Subsequently, the hardline religious interpretation gained an upper hand and accelerated the radicalisation process.

As the polemic intensifies, it culminates in takfiri (accusations of one another's infidelity) in the Muslim community. Subsequently, it creates disunity and distress in the public.

Even though these religious radicals are not militant, and do not sort out differences through violence, they are equally responsible for the rise of extremists.

The second wave of religious radicals was the product of the Soviet-Afghan war from 1979 to 1989.

Some groups of Malaysian students who were educated at religious institutions in Pakistan, India and Indonesia had participated in the Soviet-Afghan war as Mujahidin.

Unlike the first wave of religious radicals, this generation was far more extreme in religious interpretation and ideological zeal. As a result, upon returning home, the extremists had the audacity to form a militant group to overthrow the democratic government in Malaysia.

On the pretext of waging a global jihad (holy war) against the US imperialism, it attracted many naive young people in the Muslim world.

The White House's foreign policy inadvertently opened the floodgates for the third wave of religious radicals and extremists.

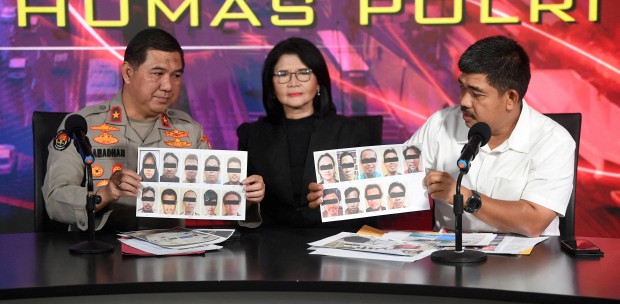

In 2001, Malaysians were awakened by the exposure of militant cells run by Kumpulan Mujahideen Malaysia and Jemaah Islamiyyah, which were later subdued by government forces.

The militant ideology is spreading rapidly among the tech-savvy youth through social media. For those who are not tempted by the beguiling calls for jihad, they are simply becoming hostile and intolerant towards those of different faiths.

Religious radicalism is a poison to multiracial Malaysia.

For instance, firefighter Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim's death during a temple riot in 2018 quickly escalated into a religiously motivated incident. Sadly, this incident has been narrated repeatedly as a Muslim versus non-Muslim issue.

When certain Islamic organisations in Malaysia decided to congratulate the Taliban, it absolutely sends a wrong message to the public.

Praising a militant in the name of religious solidarity is never appropriate.

Religious scholars must join hands in advocating a narrative of moderation as a counterweight to poisonous bigoted thoughts.

Punitive measures alone are insufficient to bring religious radicals to heel.

It will only radicalise the already radicalised person.

Therefore, a narrative of moderation within the local context is needed as a shield to protect a culturally rich and diverse Malaysia.

The writer is the executive director of NADI Centre, a consulting firm focused on strategic policy research and advocacy

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the New Straits Times