Historians remember July 18, 1918 as the day of two crucial battles of World War I when Allied forces drove the Germans out of Soissons and Chateau-Thierry in France, and the day when the Bolsheviks executed Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, effectively ending the reign of the Romanov royal family.

Fast forward a hundred years to July 18, 2018, when South Africans and most of the world commemorated the centenary of Rolihlahla Nelson Dalibunga Mandela (Madiba as he is affectionately known) as a giant of a statesman, a symbol of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa and all forms of racism, and as a hero of African liberation.

Who would have thought that the mischievous little boy born in the village of Mvezo in Transkei in the Eastern Cape and who grew up in the Thembu royal house, would go on to become one of the iconic peacemakers and statesmen of the 20th century and a living legend wooed by royalty, politicians and celebrities alike for the inevitable photograph, and by millions of ordinary people as a symbol of hope for liberation from oppression, the direness of their poverty and the indecency of the inequality that has ravaged modern society.

For a man incarcerated for 26 years together with other stalwarts of the struggle against apartheid on the infamous Robben Island prison off the coast of Cape Town, Mandela won the heart of the world and symbolised the triumph of the human spirit when following his release from Pollsmoor Prison on February 11, 1990 and his subsequent election as the first democratically-elected president of South Africa on May 10, 1994 signifying the formal end to apartheid, he humbly chose the path of reconciliation and restitution instead of revenge.

“We dedicate this day to the heroes and heroines in this country and the rest of the world who sacrificed in many ways and surrendered their lives so that we could be free. Their dreams have become reality. Freedom is their reward. We are both humbled and elevated by the honour and privilege that you, the people of South Africa, have bestowed on us, as the first president of a united, democratic, non-racial and non-sexist government,” he said in his inauguration speech.

Through the Truth & Reconciliation Commission he established, South Africans, whether the oppressors and oppressed; the gaolers and gaoled; black, brown or white, were given the chance to exorcise the catharsis of living under the inhumanity of apartheid from their psyche — a feat which no other country has thus far begun to achieve.

Mandela, despite some resistance from his baffled African National Congress comrades and wider erstwhile anti-apartheid activists, deftly and largely successfully pushed through an exercise, which its original architect newly-elected Chilean President Patricio Aylwin in 1989 failed to achieve through his National Commission for Truth & Reconciliation to investigate the brutal excesses of the dictator General Augstine Pinochet and to reconcile the seemingly intractable divisions in Chilean society.

No amount of international awards and honours, including the part-discredited Nobel Peace Prize, could make up for the sacrifices Mandela and his comrades made in their struggle for dignity and democracy in South Africa.

While Mandela’s reconciliation effort was a remarkable success, five years after his death in 2013, South Africans still rue the lack of integration between the various races and ethnic groups, the lack of land reforms, the continued economic domination of the Whites and the emerging Black establishment and middle class, the state capture of vast sections of the economy, the failure of successive ANC governments to deliver on basic aspirations of jobs, affordable housing, Black empowerment, protection of women against violence and the rising inequality between the haves and have-nots, albeit the latter is a global phenomenon.

So as we mark the centenary of his birth, what has Mandela’s legacy been to South Africa and the world? He had the first mover advantage as the first post-apartheid president. But his two terms in office were consumed by his great aura more as a statesman rather than a politician. The ANC, 24 years after coming to power, still has a problem in transforming from a liberation movement into a government.

Some of his policies were half-hearted, which contributed to the chaos successive ANC governments have presided over whether in more pragmatic Black empowerment, the marginalisation of the country’s forgotten other non-White minorities such as the Coloureds (mixed-race), Indians and Cape Malays, the policy

towards HIV, especially given the death of one of Mandela’s own sons from it and South Africa having one of the highest incidence of the disease in the world, socio-economic reforms which saw the enrichment of a small section of Black society and the enhancement of inequality amongst the masses, and eradicating corruption.

Mandela’s choice of Thabo Mbeki as his successor proved to be highly flawed. The haughty Mbeki, educated and politically nurtured in the UK, became the HIV/Aids denier of South African politics. His successor Jacob Zuma, perhaps the most disastrous of Mandela’s successors whose state capture of chunks of the economy is legendary, boasted that HIV could be washed off with a shower.

Both Mbeki and Zuma were ousted by the ANC. How many terms new President Cyril Ramaphosa will survive remains to be seen, especially with the threat of a divisive new Mining Charter and the controversy of ‘Expropriation Without Compensation’ looming.

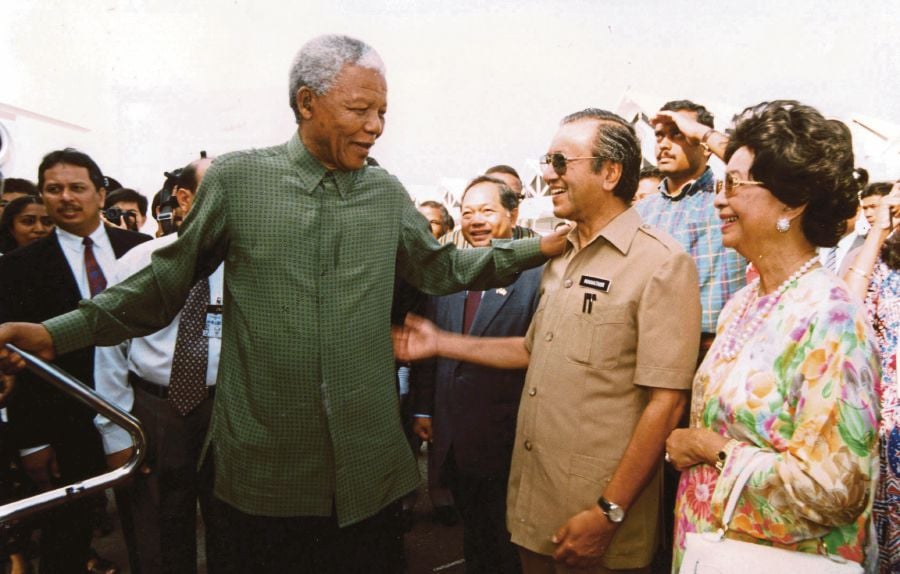

In foreign policy, Mandela achieved greater success as a role model for Africa and other emerging countries. His support for the Palestinians was strong, and he persuaded Col Qaddafi of Libya to abandon his nuclear ambitions paving the way for the lifting of UN sanctions. Malaysia was one of the strongest supporters of the ANC during its fight against apartheid. Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad was the first foreign leader to visit Mandela after his release in 1990.

He promptly dispatched foreign minister Tun Abdullah Badawi (Pak Lah) to Cape Town for meetings with ANC officials to offer logistical, training and other support.

I was visiting Cape Town at the time and Pak Lah invited me to a dinner in honour of the ANC hierarchy, in which he reiterated Malaysia’s unflinching support to Mandela and post-apartheid South Africa.

Mushtak Parker is an independent London-based economist and writer