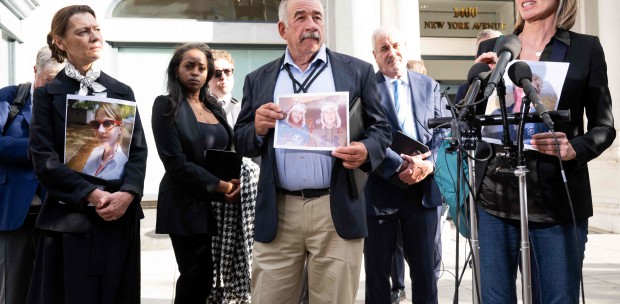

AFTER four years of agonising and waiting, are the relatives — of the 298 passengers who died on Malaysia Airlines MH17 after it was downed in eastern Ukraine in July 2014 — finally going to get justice?

Last week a Joint Investigation Team (JIT) led by Dutch, Malaysian and Australian investigators, removed any doubt after an exhaustive exercise in a detailed report that the missile that brought down the plane belonged to the Russian 53rd anti-aircraft brigade in Kursk and that “all the vehicles in a convoy carrying the missile were part of the Russian armed forces”.

The Netherlands and Australia, who lost 193 and 27 nationals, respectively, in the tragedy, are holding Russia responsible for the downing of MH17. Some 43 Malaysians also perished in the disaster together with victims from Indonesia, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Germany and Philippines.

Predictably, Moscow rejected the findings and the involvement of any of its weapons in bringing down MH17, instead blaming a Ukrainian military pilot, Capt Vladyslav Voloshyn, who had flown a series of missions against the Russian-backed rebels, and who allegedly committed suicide in March.

Are the relatives of those who perished any nearer to getting justice for their loved ones? The JIT Report and its conclusions are an important step towards achieving that goal, but, when it involves a superpower as the perpetrator, the wheels of justice have a habit of slowing down due to a cornucopia of obfuscations, some of them bordering on the preposterous.

Resolving the MH17 tragedy and getting recourse for the relatives will require creative diplomacy and utmost resoluteness on the part of the Netherlands, Malaysia and Australia, the troika of countries most affected, and the international community. Resolving it will also preempt similar incidents in the future and uphold international law.

The precedents are mixed. When Pan Am Flight 103 exploded over the Scottish town of Lockerbie in December 1988, it took 13 years to convict Libyan Abdelbeset al Megrahi for the bombing in a Scottish court convening at the “neutral” Camp Zeist in Holland. The bombing killed 259 passengers and crew, along with 11 people on the ground.

Two years later, president Muammar Gadhafi of Libya agreed to pay US$2.7 billion in compensation to the families of those killed. A year later Washington and Tripoli resumed diplomatic ties after a break of 27 years.

The carrot-and-stick approach worked. The carrot was lifting sanctions against the Libyan regime and resumption of diplomatic ties. In return Libya would hand over the suspects in the Pan Am bombing to the United Nations. The bonus was that Libya would renounce any nuclear arms ambitions and would cooperate in president George W Bush’s “War on Terror”.

The reality now is Russia is not Libya. Russia suffered its own aviation terrorist incident in October 2015, when Metrojet Flight 9268, on its way home carrying 224 passengers and crew from the Egyptian resort Sharm el Sheikh, was brought down by a bomb over Sinai.

There was a consensus that it was a terrorist bomb planted by the Islamic State (IS). Perhaps, it was that dastardly act that edged President Vladimir Putin to support President Asad in the Syrian civil war and take the fight to IS.

Engaging with Putin, fresh from his recent “landslide” presidential election, is going to be more complex. Moscow is smarting from sanctions imposed by the United States, United Kingdom, European Union and others in the aftermath of the poisoning of former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal and his daughter Julia in the UK. The deed points the finger at Russian involvement. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov wasted no time in drawing parallels between the blame apportioned in the MH17 downing with that of the poisoning of Skripal. It seems Russia is using the same tactics of casting doubt on the integrity of the investigations, including the exclusion of Russian officials, and dismissing the exercises as politically-motivated.

The quest for justice for the victims of MH17 and their relatives may seem bleak. The resolve of the Dutch, Malaysian and Australian authorities cannot dissipate in the face of Russian intransigence. That would be an abdication of responsibility.

The Foreign Affairs Ministry, in a statement last week, stressed that, “Malaysia is resolved to seek justice for the victims of flight MH17. It remains resolute in the pursuit to prosecute those responsible”.

At the time of writing, Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad had yet to name his foreign minister, who will prove vital in engaging with the Dutch and Australian counterparts to decide on criminal investigation and proceedings, and any diplomatic offensive.

Legal routes, as the Lockerbie bombing showed, will be lengthy and not easy. According to Dr Sergey Vasiliev, Assistant Professor of Public International Law, Leiden University, speaking to the BBC, the first step would be to try and “negotiate” a solution diplomatically, “which could take the form of an acknowledgement of responsibility and apology, full inquiry and disclosure, domestic criminal proceedings against those responsible, and compensation to the families of victims”.

As long as Moscow continues denying any involvement in MH17, this option seems highly unlikely. Failing that, the troika could initiate a case against Russia before the International Court of Justice in The Hague or file an inter-state application with the European Court of Human Rights against Russia.

For the victims and their relatives, once again an act of wanton terrorism seems to be confined to the vagaries of geopolitics. The international community seems yet again impotent in confronting a scourge that shows little sign of going away.

Justice indeed, can be very elusive even on the cusp of the 21st century!

Mushtak Parker is an independent London-based economist and writer