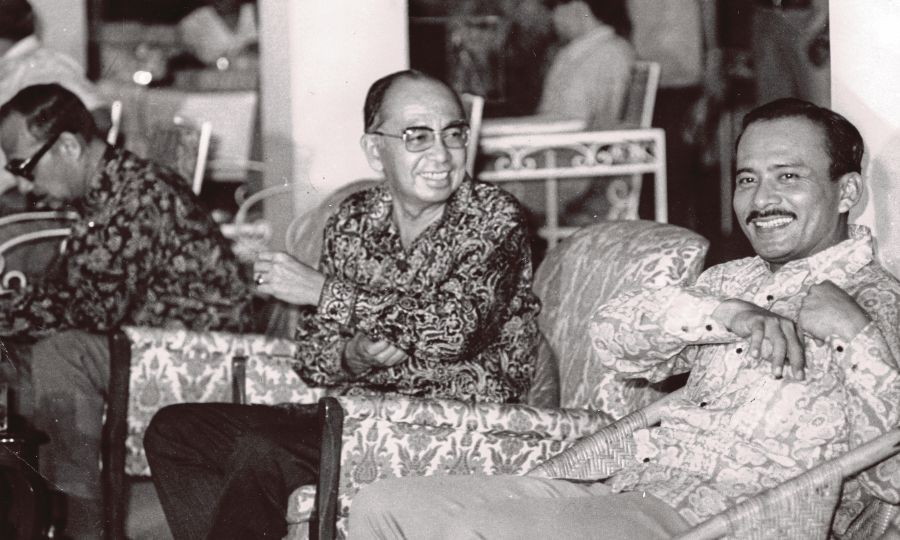

KUALA LUMPUR: He was known as Tun Abdul Razak Hussein’s “shadow”. Wherever the second prime minister went, Tun Mohammed Hanif Omar will not be too far behind. He is said to be the best person to talk to if anyone wants to know about Razak.

Hanif was 23 years old when he first served as Razak’s security detail in 1962, when they went to Bangkok to meet the then Thai foreign minister Tun Thanat Khoman to explain about Maphilindo, the proposed non-political confederation of Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

“After one night in Bangkok, we went to Phuket for meetings. We then went to Hua Hin, where Thanat was kind enough to loan us his two-room wooden chalet. Razak took one room and I took the other. The only other person there was the cook.

“We talked. He asked about my background. From there on, he would ask me to follow him on his trips.”

On his first impression of the man he had served as aide-de-camp for five years, Hanif said he heard people describing Razak as a dour man.

“He had a stern visage, but he was kind.”

He first heard about Razak when he was at Malay College Kuala Kangsar. Razak’s brother was Hanif’s senior by one year. His classmate, Dollah Kok Lanas (the late Tan Sri Abdullah Ahmad), had met Razak in Kuala Lipis.

And, it was only Hanif and people in Razak’s inner circle who knew how much he liked to crack jokes and recite poetry.

“He knew the poetry by heart. I learned poetry in school, too, but I couldn’t memorise them like he did.”

Razak, too, was not only a good judge of character, but he prided himself on having the uncanny ability to be right about his first impression of people.

“He can detect a person’s quality by the first look. Once he has a bad first impression of you, you have to move a mountain to make him change his mind,” Hanif said.

To the 78-year-old former inspector-general of police, Razak was not only a kind, caring and generous boss, but he was a truly compassionate man of highest integrity and honesty, who put the interest of the nation and the people above all else.

Razak’s integrity, he said, was “almost unbelievable”.

“Just imagine this. He was the director of operations of Mageran (National Operations Council). The cabinet was not functioning. Parliament had been suspended. He had the sole power. He could hold on to that power, but he didn’t.”

Mageran was the emergency administrative body formed to restore law and order in the country following the May 13 incident in 1969. It governed the country from 1969 to 1971, when it was dissolved with the restoration of Parliament.

Hanif said during Mageran rule, non-Malays were fearful of Razak replacing Tunku Abdul Rahman as prime minister as they expected him (Razak) to be racial in his policies. At the same time, Malays were dissatisfied with Tunku over Malay rights.

“They (Malays) said ‘just wait when Razak takes over’. They think he will be less accommodating to the other races.

“As head of the Special Branch for Selangor then, I told my non-Malay officers that when Razak takes over, you will be surprised while the Malays will be disappointed. He was not what people thought of him. He had many friends of all races and walks of life.

“He grew up in a Britain that was quite strongly socialist. And, coming from a country like ours that was administered by the British, he, including Tunku and even (then Singapore prime minister) Lee Kuan Yew had strong streaks of socialism in them. They believed in helping the people at the bottom.”

Razak was also noted for being a tightwad, especially with the government’s money.

“Razak had these premonitions and often enough, when we were overseas, he would worry about things back home. He would ask me to send telegrams to Tunku to ask if everything was all right.

“And then, he would ask why the telegram could cost so much. I had to tell him that they count every word and that if it was a long message, it was going to cost a lot. He asked for the draft and counted every word.”

While he was frugal with the government’s money, he was generous to a fault with his own, “which he didn’t have much. He bought mostly on credit and the bank manager told me he would take six months to settle it”.

On a few occasions, Hanif was the beneficiary of his generosity — shoes from Hong Kong, which were more expensive than the ones Razak bought for himself, and a winter vest.

On trips abroad, he would buy souvenirs for his wife, Tun Rahah, such as pouffes from Cairo, which he paid using US dollars rather than Egyptian pounds as the pouffes were cheaper that way.

He even wanted to buy “paste” (fake jewellery) for Rahah when he was in London as he couldn’t afford to buy her real ones.

Razak, too, never threw his weight around when he was prime minister.

“He had a small house in Petaling Jaya. He wanted to buy a bungalow belonging to Selangor Properties in Bangsar, which was priced at RM2.20 per sq ft.

“This was because of one of his premonitions. He was worried that if he was killed, it would be hard for Rahah to send the boys to school. He wanted to buy a house nearer to their school.

“He couldn’t afford it. He asked for a reduction, but they didn’t give it to him. He just walked away.”

Hanif said Razak had done much during his time in office, especially for Malays with the setting up of Bank Bumiputera, Urban Development Authority and Felda.

He and his deputy, Tun Dr Ismail Abd Rahman, could possibly had “worked themselves to death” because they knew that they didn’t have much time on their hands.

Dr Ismail, who had a heart condition, died in 1973, while Razak died of leukaemia while seeking treatment in London in 1976.

Hanif, who is the chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Razak Foundation, shared much more about Razak in a book, Fulfilling a Legacy, which would be launched on Aug 29.