AWELL-THUMBED paperback comes into view while searching for references in the study. Almost immediately, memories of several pleasant evenings spent delightfully poring over The Golden Chersonese: The Malayan Travels of a Victorian Lady overwhelm thought.

An evocative account of 19th-century Malaya told through a collection of 23 letters written by Isabella Lucy Bird to entertain her ailing sister back home in Scotland, this delightfully illustrated tome touched on many captivating local aspects and gave vivid representations of what life was like in this country some two centuries ago.

Delving into the catchy title, related texts reveal that the term "Golden Chersonese" was first coined by ancient Greek and Roman geographers in reference to the Malay Peninsula, which, for centuries, was renowned for the precious metal as African countries are collectively for diamonds currently.

LAND OF GOLD

Later, prolific 17th-century Malay-Portuguese writer Manuel Godinho de Erédia determined that production was primarily centred in Pahang as open-cut mines had already been established in the area over the past six centuries by the Mon Khmers, an industrious and resourceful group of Cambodians whose vestiges had marked outcrops throughout Southeast Asia. As fame continued to spread far and wide, numerous legends began postulating Pahang as the El Dorado of the East with one of King Solomon's many fabled mines said to be located within the vicinity of Raub town.

Believed to have been established around the 18th century, Raub was believed to have come into existence when a group of men, out searching for forest produce, happened to chance upon an ancient mine that had been left abandoned by the Mon Khmers after their civilisation fell into decline. The abundance of clean water and edible wild fruits nearby gave the men reason to start clearing the surroundings and set up temporary camp.

Employing the meraup technique with their hands to remove sand near the flooded mine, the unsuspecting foragers began uncovering, much to their elation, small gold nuggets. Pleased with the unexpected windfall, they were said to have named the place Raup in reverence to the relative ease of acquiring good fortune. As time passed, the name morphed into the Raub that we know today.

Mining methods employed by local prospectors who began converging in Raub not long after that were no different from those used by the Mon Khmers. The depth of their work, in most cases, was limited to less than 15 metres owing to constant inundation by torrential rain and the locale's naturally shallow water table.

INTERNAL STRIFE

Traditional gold mining, however, began taking a back seat when the British extended their reach to Pahang following a six-year civil war between the two sons of Bendahara Tun Ali who vied for the throne following their father's demise. Hostilities began in November 1857 when Tun Wan Ahmad launched an attack on his brother Tun Mutahir after the latter failed to execute their late father's wish of granting tax revenue from Kuantan and Endau to the former.

Although Wan Ahmad's eventual victory in 1863 led to his proclamation as sultan and the formation of the modern Pahang sultanate, the Pahang economy, by then, was in shambles. In the decade that followed, the British abandoned their non-intervention stance in order to protect important colonial interests in the state. By October 1888, Sultan Ahmad reluctantly accepted John Pickersgill Rodger as Pahang's first British resident.

Despite the return of some semblance of normalcy, trouble once again began brewing in Raub with the emergence of two mining rights claimants. An initial concession that had been granted by Sultan Ahmad to Raja Impi, an influential Selangor native, was abruptly withdrawn and awarded instead to Syed Mohammed Alsagoff of Singapore when insufficient or completely no royalties on gold extracted were forthcoming.

Deeply slighted, an enraged Raja Impi used his vast influence to muster a force strong to drive off Syed Alsagoff, as well as the 200 men sent by the sultan to aid the latter. Unwilling to waste vital resources on what would probably end up as a protracted dispute, Syed Alsagoff dispersed his trusted followers throughout the region in an effort to search for better business prospects.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY

One of them headed to Borneo and happened to cross paths with William Robert Sefton, an itinerant Australian prospector partly credited with the 1876 Hodgkinson goldfield discovery in Palmer, Queensland. Taken in by stories of untold riches in Raub, Sefton immediately made plans to meet Raja Impi and subsequently made him such a lucrative offer that an option to buy the concession was secured without much hesitation.

Realising that opportunity was at hand for him to once again make history, Sefton lost no time in forming an Australian syndicate, which quickly entered into a legally binding agreement with Raja Impi to buy an area of 20 square miles in Raub for the then considered princely sum of £10,000.

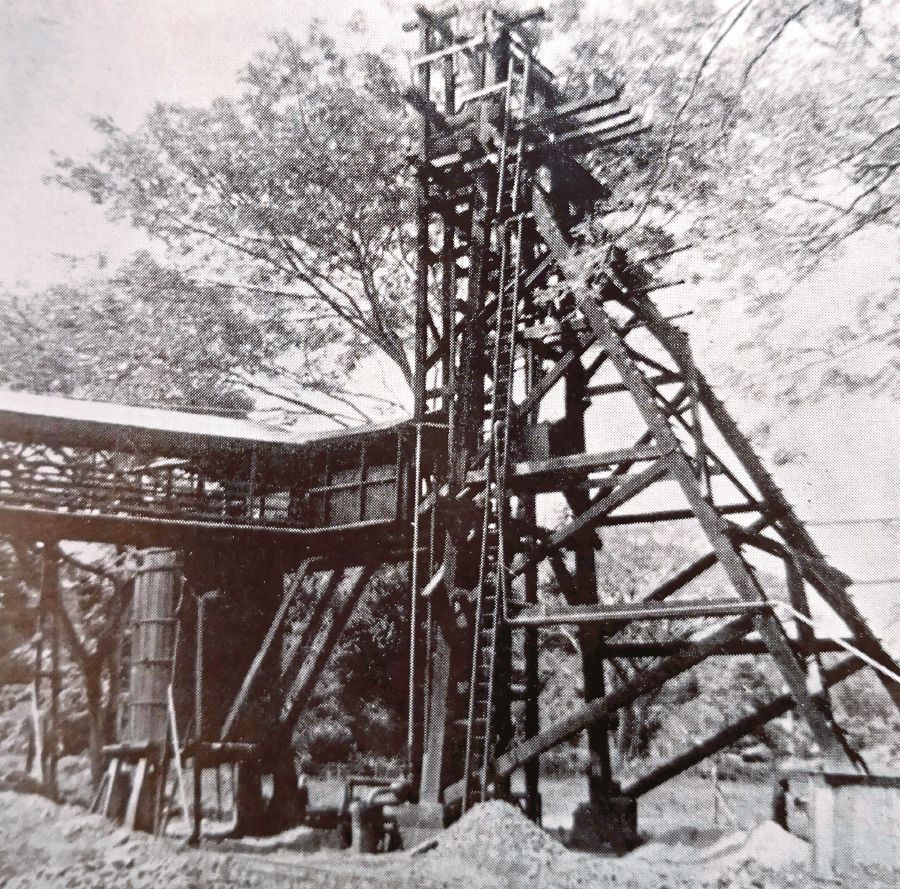

The syndicate then registered a company in Queensland under the name of Raub Australian Syndicate Limited in 1889. After much preparations, the appointed manager, Walter Bibby, set sail with an arsenal of boilers, pumping plants and stamping mills. Landing in Pekan on the Malayan east coast, the precious state-of-the-art equipment was brought to Raub via the Pahang, Semantan and Bilut rivers.

AUSTRALIANS MOVE IN

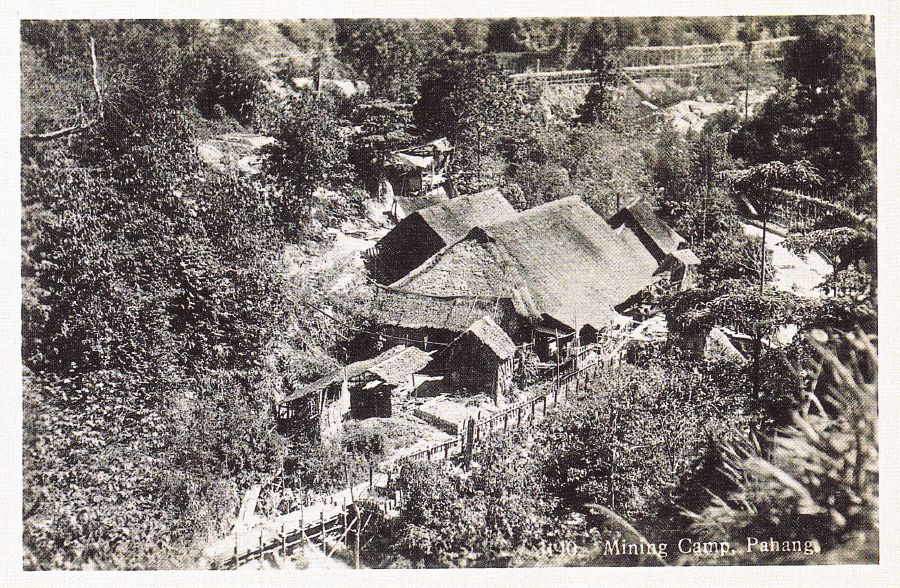

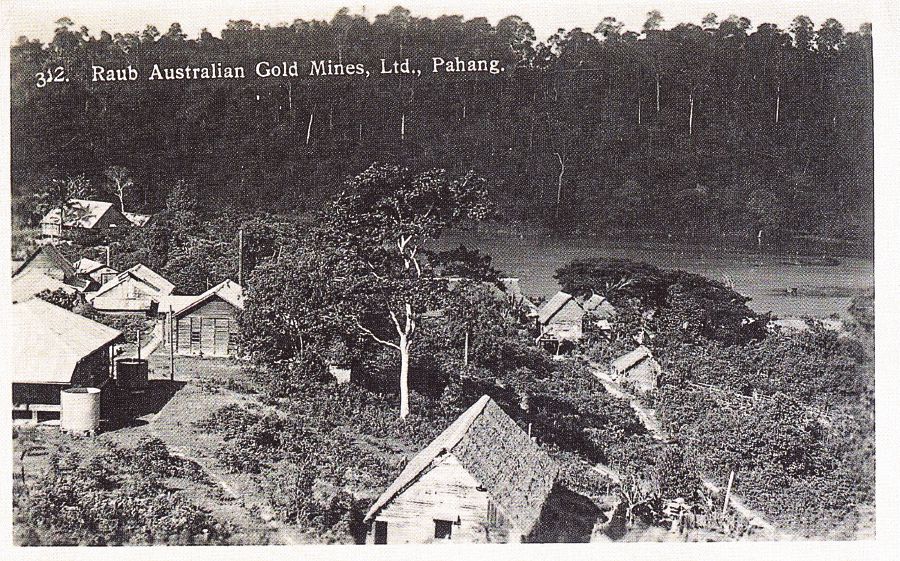

A collection of early 20th-century postcards in an album on a nearby shelf heralds a flood of pleasant recollections related to their acquisition from a renowned Danish auction house more than a decade ago. Within its leaves are a few featuring the famed Raub gold mining area. Their depictions of rudimentary buildings set amidst dense jungle give a rather vivid representation of how challenging things must have been for Bibby when he finally arrived with the tide in September 1889.

As work began, early enthusiasm was quickly brought down several notches after initial forays yielded disappointing results. Despite this preliminary setback, the syndicate soldiered on with conviction that it was just a matter of time before a rich vein became common knowledge. In order to increase efficiency, reconstructed operations were placed under a more nimble entity known as the Raub Australian Gold Mining Company Limited in 1892.

The revamp, however, failed to immediately deliver the expected positive results as an anti-colonial uprising initiated by local Malay chieftains headed by Dato Bahaman hit Raub like a full-blown raging tempest just a month later. The resulting chaos placed the mining area in a state of siege for some eight months during which a large Sikh police garrison was hurriedly despatched from Selangor to provide the heavily barricaded European residences with round-the-clock protection.

True to the saying that the sun shines brighter after a storm, a bountiful deposit was uncovered soon after work resumed following Dato Bahaman's retreat north. The discovery brought sighs of relief from all concerned and, more importantly, provided the much-needed resources to start excavating other sections along that promising vein.

JAPANESE INTERLUDE

Work at the Bukit Koman section started in 1894 and the following year, activity reached vital spots at Bukit Jalis and Bukit Melaka. Increasing prosperity over the next four decades saw mine population reaching an astounding 3,500. Apart from maintaining its own police force of 40 men, the company catered to the needs of its employees by establishing shops selling all sorts of provisions at Bukit Koman village.

The good times, however, came to an abrupt halt when news of Japanese advancement came in late December 1941. Determined to prevent the precious metal from falling into enemy hands, engineers were ordered to set in motion predetermined scorched-earth procedures by setting off charges to seal major mine entrances.

With most of the European staff members placed in Kuantan and Pekan prisoner-of-war camps, Japanese administrators began granting mining leases to locals, who took the easy way out by siphoning deposits from exposed areas and steered clear of flooded and demolished sections that required substantial investments.

Surviving employees had a rude shock after returning to their workplace some six months after the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. Not a single building was left standing and all the mine shafts were badly damaged and completely flooded. Conscious of a lengthy and difficult reconstruction job that lay ahead before full production could recommence, their deafening silence echoed a thousand heart-wrenching emotions.

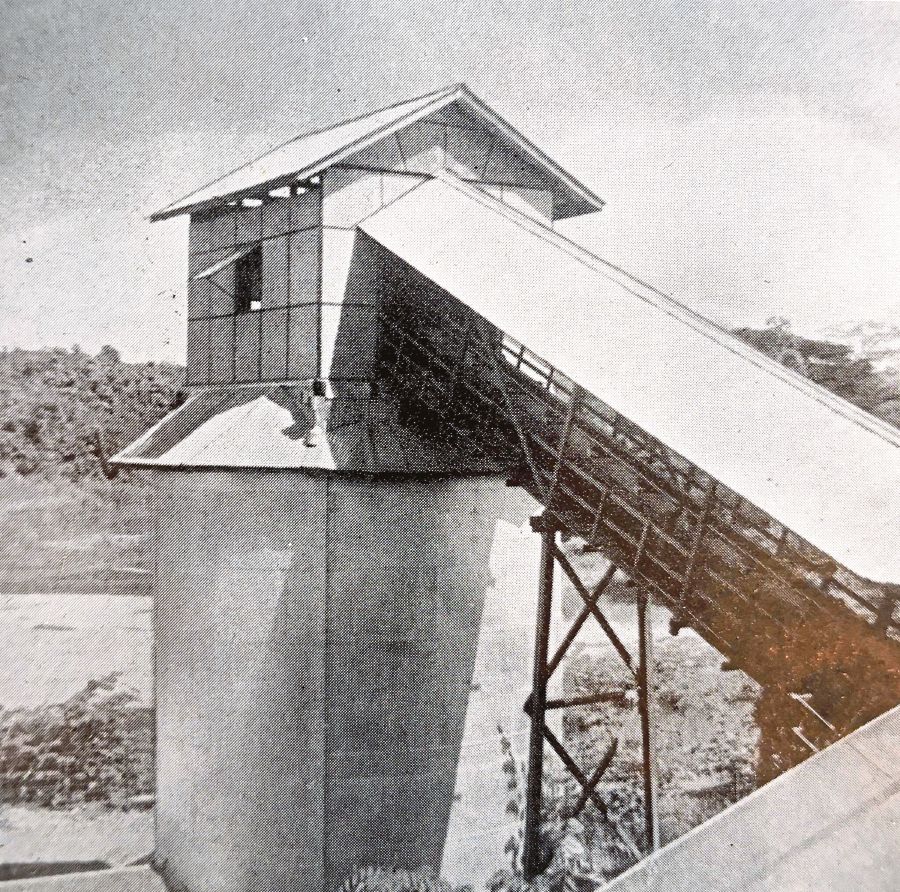

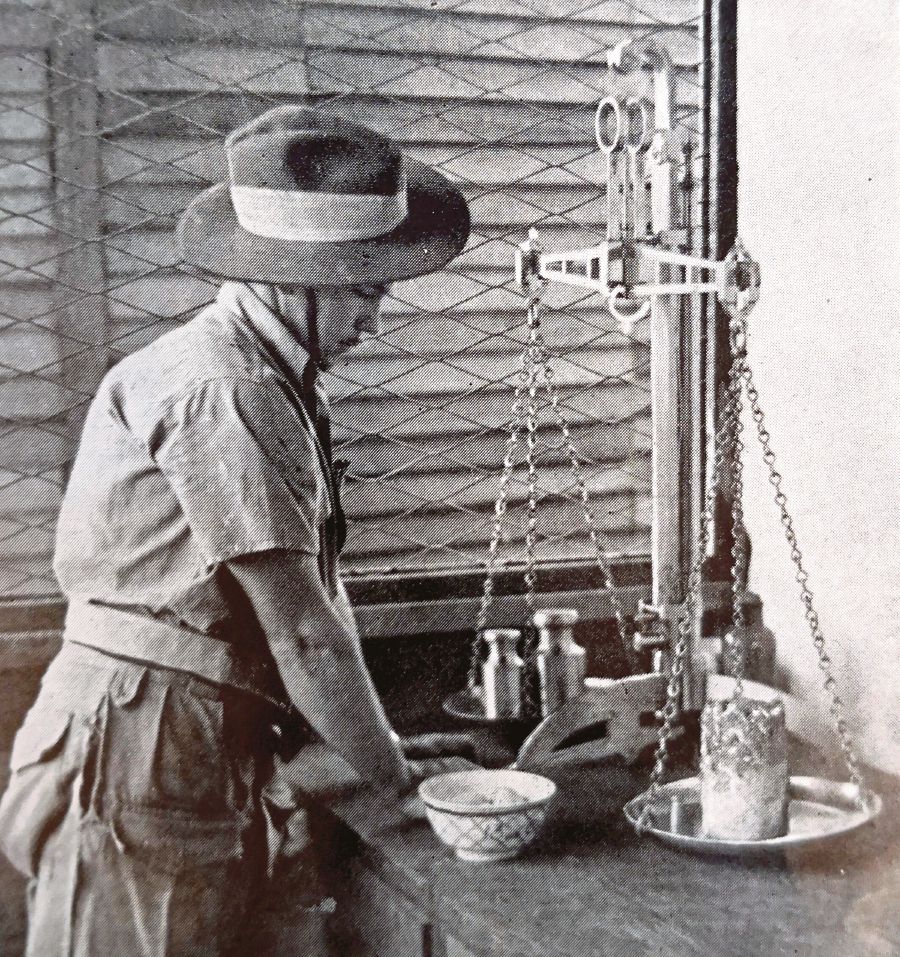

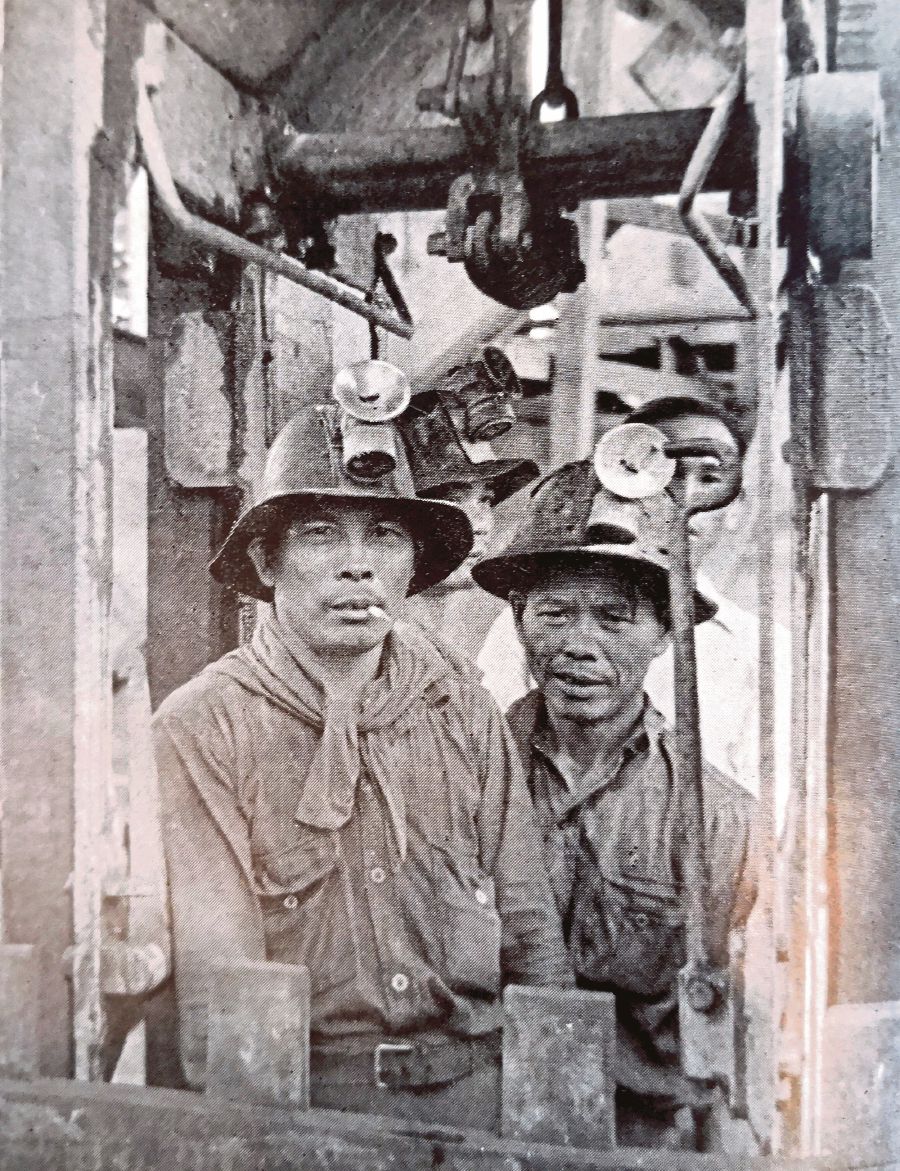

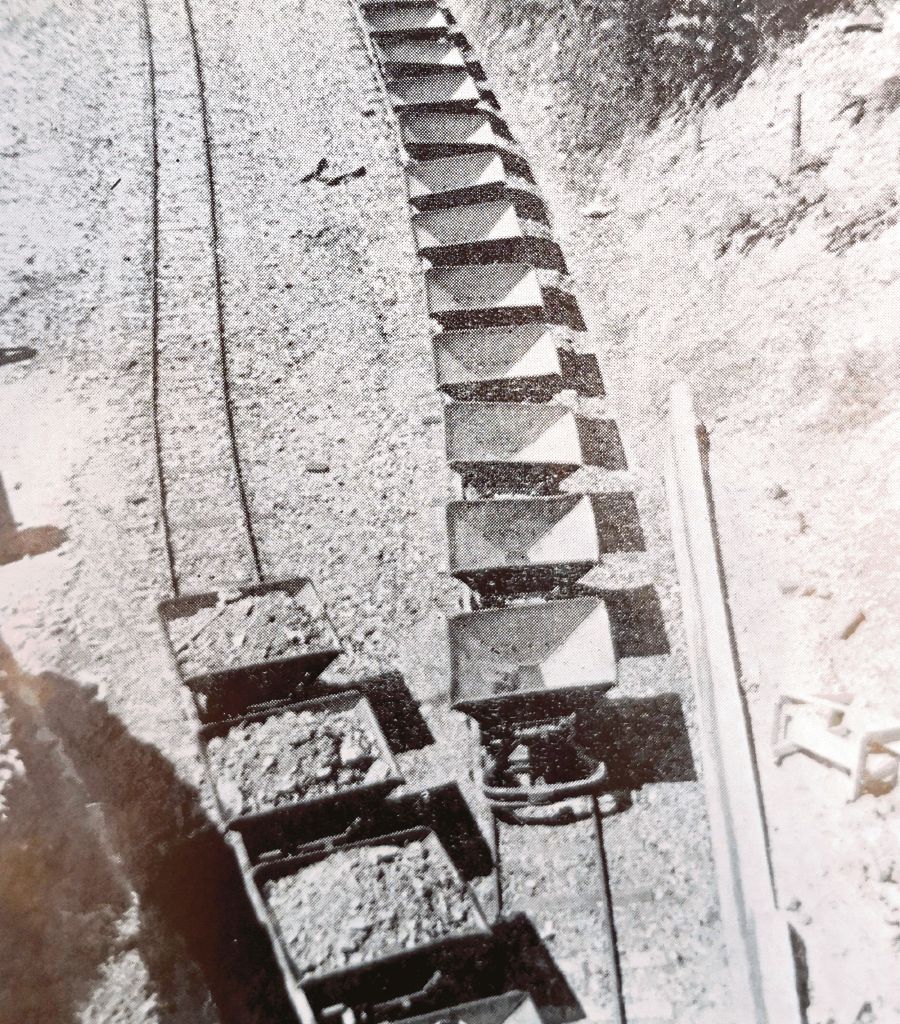

Contrary to popular belief, bulk gold production is anything but easy. Starting with courageous hard-hatted miners, whose daily work routine involved boarding metal cages that descended some 250 metres down dark and desolate shafts and tunnels, the ore was extracted and transported upwards in the opposite direction before reaching the mill, where powerful hydraulic machines pulverised them into fine powder. Finally, inclined copper plates awash with mercury were employed to separate the gold from its impurities.

Almost all motive power needed for mining and milling operations was supplied by electricty from the nearby Sempan hydro station. The first-of-its-kind in this part of the world, this pioneering renewable energy source was officially opened by Pahang resident Hugh Clifford back in 1898.

It took the concerted effort of all concerned to make everything shipshape within a few short months. Even the 12-year Malayan Emergency, which began in 1948, failed to put a dent in the operations that were up and running at full capacity.

Despite the constant threat of communist attacks, there was never a shortage of labour. Apart from the unscrupulous few who occasionally gave in to temptation by quietly pocketing the odd piece of gold-bearing rock, the vast majority of employees were just too grateful to be given the opportunity to earn an honest living and, at the same time, be part of a unique industry, which, to this very day, produces a truly glittering precious asset that contributes to our nation's lasting prosperity.