The deaths in the Orang Asli Batek tribe in Kelantan have thrown a spotlight on the welfare and survival of indigenous people. In a three-part series, AZDEE SIMON AMIR and photographer AIZUDDIN SAAD take a look at the challenges they face

LIFE for the Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia has been anything but easy. It is as rough and challenging as the paths and tracks leading to their remote villages deep in the forests.

The fact is, many Malaysians do not know much about the Orang Asli, or how the disappearing rainforest as a result of economic activities can pose a threat to their ancient practices.

Lately, the deaths of Batek tribe members in Kelantan have thrown a spotlight on the hardship that the Orang Asli face. But that was not the first time they became victims of tragedy.

For one Semai village in Tapah, Perak, it took a disaster to initiate action to improve their lives.

The village, Pos Dipang, was inundated by a mudslide in 1996 after torrential rain. Forty-four people lost their lives, 29 of them Orang Asli villagers.

According to a villager known only as Shafie, 48, many changes for the better took place after the disaster, which he believed was caused by old logging debris being washed down the barren hillslopes during the storm.

“Before that tragedy, there were no roads going to our village. Neither was there electricity or piped, clean water. We didn’t have modern homes that some of us live in now.

“But soon after that terrible mudslide, development came to the village. With the main road that was built, came other amenities such as the school and government clinic,” said the rubber tapper and odd job labourer.

However, he said there was still not enough progress and development for his people.

“It’s not just for our community, but most of the other Orang Asli communities as well, especially those living in rural areas and forests.”

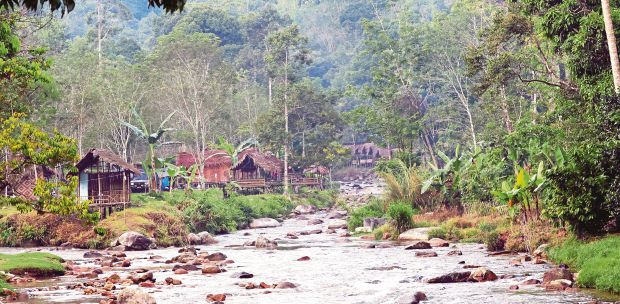

He is right. There are, for example, no paved roads into the remote Semai village of Ulu Ruai in Raub, Pahang, and the Temiar village of Ong Jangking near Gerik, Perak.

This makes it very difficult to deliver aid and provide education and healthcare to the Orang Asli there.

However, the cluster of villages in Ulu Ruai are luckier than the rest as organisations, such as the Rotary Club of Bukit Bintang and Persatuan Komuniti Kasih Selangor (PKKS), frequently organise medical visits to provide basic healthcare, such as deworming, and lice and skin treatment.

“We are very thankful to these organisations for sending in medical teams from time to time to treat our ailments.

“Their visits help us a great deal because transporting sickly folk, such as the elderly and pregnant women, can be risky, especially while travelling on rough tracks like the one to our village.

“Government clinics and hospitals are far away,” said Pastor Yakhem, 56, an elder of Kampung Bertang in Ulu Ruai.

The Health Ministry does send its personnel to visit the villages, but they are unable to come often.

There are 869 Orang Asli communities in Peninsular Malaysia, with slightly more than 60 per cent living on forest fringes.

Despite the government setting up the Orang Asli Development Department (Jakoa) to look into their welfare, many villages and settlements still have not experienced progress.

Basic amenities, such as electricity, piped water, schools, healthcare services, proper roads and modern housing are lacking in some communities.

A few years ago, Jakoa attempted to improve the lives of the Semai villagers in Ulu Ruai by building a water supply system with pipes, water pumps and storage tanks, but sadly, that did not work.

“They came, they saw, they listened. Then they built the system but sadly, it never worked from day one,” said PKKS member Choy Lee Wan.

“There is a contact number on the notice board at the storage tanks to call in case of an emergency or breakdown, but the number is not in service.

“So, the villagers just continued to rely on a nearby stream for water as there’s nothing else that could be done.

“But currently, the Rotary Club of Bukit Bintang is reviving the effort by building a new water supply system that taps into a nearby source up on the hill. Once this is up and running, the villagers can enjoy piped water,” he said.

According to Pos Dipang resident Shafie, he and his fellow Semai villagers have not seen a Jakoa officer in months.

“Our village is near Tapah, so we are not a remote village. But we have not received a visit from Jakoa officers for some time.

“Those days, they used to visit us once every two to three months. When they come, they carry out observations, listen to our issues and take down requests, such as the need for modern housing, which we have been requesting for quite some time but to no avail.

“Sadly, apart from these, nothing else had happened. If we are feeling left behind, just imagine what our fellow Orang Asli who live in the forests must be going through.”

Many Orang Asli tribes, especially those living deep in the forest, are at risk of being displaced due to logging and other economic activities.

One example is the Temiar people of Kampung Tasik Asal Cunex, who live deep in the forest between Gerik and Sungai Siput in Perak.

They are fighting to stay on the land that they have lived on for generations. Their plight gained national attention recently when they erected blockades to prevent logging near their village, which has been permitted by the state government.

The villagers are determined to stop the loggers from clearing the forest that they have depended on for their livelihood.

Kampung Tasik Asal Cunex headman Pam Yeek, 46, was adamant on remaining on their land despite being pressured to relocate by the logging company and state authorities.

“There are more than 30 of us putting up the blockades. We are not just from Kampung Cunex, but also five other villages, because the logging will destroy the land and affect our way of life.

“We have lived peacefully for years despite the lack of aid and assistance from the authorities, and we have never caused anyone problems. All we want is to be left alone to continue with our way of life, which is not too much to ask.

“Despite being offered compensation, we rejected it because we were neither consulted nor involved in discussions, which were held with a ‘Tok Batin’ (headman/village chief) appointed by Jakoa. The department does not represent us or understand our concerns,” said Pam.

Logging and forest clearing to convert the land for agricultural use greatly reduces the territory for wild animals to roam.

Besides pushing many species to the brink of extinction, some animals like wild boar are hunted by the Orang Asli for food.

According to Temiar villager Ramli, 32, who lives in Ong Jangking located deep in the forest of Gerik, the shrinking territory of wild animals has adversely affected the Orang Asli living in the same area.

He said ever since the forest near his village was cleared, dangerous encounters between villagers and wild animals, such as tigers and elephants, had become frequent.

“We don’t call them elephants. To us, they are known as Atok or Orang Besar, because they lived and roamed this forest longer than we have.

“We’ve never had problems with wild animals coming close or into our village before this.

“However, all the land clearing has driven them off their habitat and caused them to come dangerously close to our village.

“A few months ago, a large herd of elephants came through and damaged some of our homes, but luckily, the damage was not severe and most of us managed to evacuate in time to avoid a worse outcome.

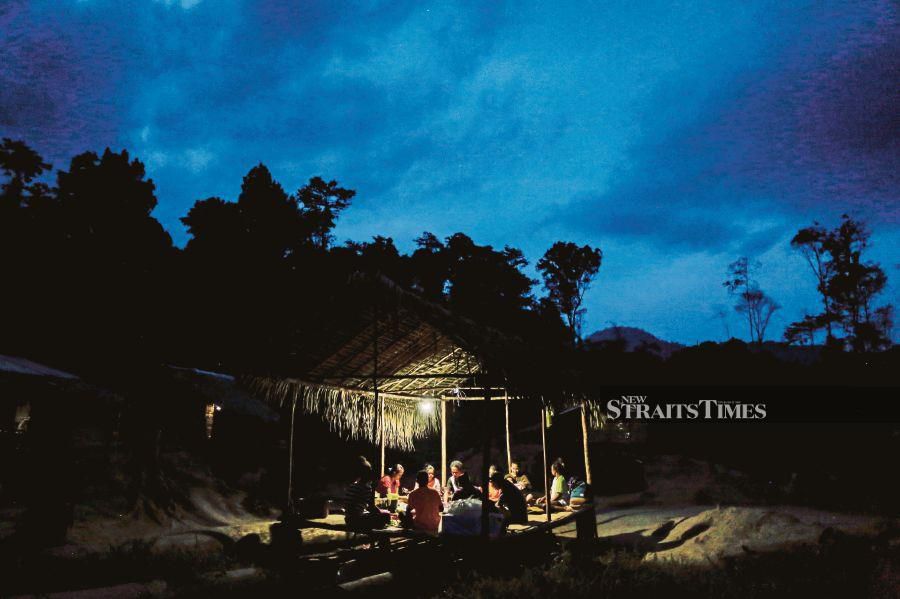

“So now, a few of us take turns to keep watch for approaching animals every night. We also put logs around our village to form a barrier. All the land-clearing and logging has threatened the animals and our way of life.

“We depend on the forest for more than just food. With the forest fast disappearing because of development, what will happen to us?” said Ramli.