THEY say that the journalist is the first historian and that the writing of the scribe is the first draft of history. In recent weeks, I was engaged in several events integral to the narrative of journalism.

One was my talk on the functions of journalists and journalism as a profession and an institution. My initial response was that journalism functions in producing news and views. These are integral to the journalistic enterprise.

At the same time, journalists are witnesses to history. To understand how the journalist makes history, we have to examine journalism as knowledge — a science and an art.

On one occasion, I narrated what the scribe is (or should be understood as such), with regard to conceptualising journalism. At the recent Malaysian Press Institute National Media Forum, I reminded the audience, comprising journalists and academics, that we have to reconstitute journalism as a body of knowledge.

Subsequently, I addressed the problem of journalism as an object of inquiry. There certainly is a misrepresentation on the subject of journalism.

In 30 years of my academic life among journalism educators in the country and the region, it is on rare occasions that I encountered an interest on journalism as a conceptual and theoretical mode of inquiry, having a corpus and a philosophy.

The thinking that has represented journalism in the country is that it is a practical discipline with much of the teaching and research involving writing (and editing) skills in the guises of introduction/principles/fundamentals of journalism, news-gathering and writing, copy editing, newspaper/magazine production, online journalism, opinion and feature writing, economic journalism, and law and ethics.

In recent times, we find course titles such as international journalism, multimedia journalism, and technology and journalism in response to perceived (market) needs or thrown in for good measure into the curriculum.

Courses on the sociology of journalism, journalistic genres, history of journalism, journalism as a profession and ideology or journalism and philosophy do not appear in journalism and communication schools.

I suppose too that the journalism student is not exposed to various writing genres — fiction and non-fiction. Much thought of (and taught) as a vocational course in Malaysian as well as many universities in the region, the subject of journalism needs to be reoriented and contextualised.

Further, the word “media” and all its ramifications have hijacked the meaning of journalism. Journalism is media, but media is not necessarily journalism. Media is a catchword embracing an amorphous galaxy of subjects and objects. In the McLuhanian sense, it may mean everything, or nothing.

We are in a media sphere which penetrates into every fibre of our transaction, thought, impression and emotion of the immediate and remote reality. Journalism now exists in many media platforms, but that does not mean that we have to substitute media for journalism.

I also argued that the Press (or if we mean the media) as the “fourth estate” is a feature of the past. Taking journalism to be a cognate of media, it is a sphere, dominating, intruding, influencing, producing and reproducing every aspect of society, government and governance.

We can no more see the “fourth” branch of government existing independently and acting as the sole conscience of society.

The institution of journalism not only mediates in the processes and functions of government, it also, through the ubiquitous media technology produces, consumes and reproduces facts, values and interpretations.

It mediates and adjudicates. It tends to blur social and political functions, conventions and formalities.

The event, movement or idea, witnessed and constructed through the profession of journalism, become cause and effect at the same time. We cannot assume that society and governments live in isolation from the journalistic media.

Note that I have used media, journalism and journalistic media interchangeably. One senior journalist raised the issue of social media, linking it to citizen journalism and commenting that news gathered by users of new media are done without a sense of ethics and the conventions of the profession.

And then there are the perennial concerns — at times ambivalent, at times unforgiving, on the media council — the self-regulatory mechanism that has been the subject of discussion and much heightened debate over the last 15 years when a proposal was submitted to the government through the Malaysian Press Institute. Such a council, however, was first mooted during the time of Tun Abdul Razak.

This brings us to another problem — who is a journalist? Can anyone with a smartphone — capturing videos and transmitting/twittering or re-twittering events and other happenings — be called a journalist?

And bear in mind that journalism is not only about events, it is about ideas, movements and dynamics — both the tangible and intangible. Be reminded that both news and opinions are integral to the journalistic enterprise.

And both the news and opinion are generic genres in the literary and social functions of journalism. Both are subject to an array of abstractions and concepts — it is not only writing skills.

It is thought, factuality, objectivity, interpretation and imagination. It is semantics and representation.

And construction and deconstruction. And surely, journalism is cultural and intellectual expression.

Such themes pertaining to thought, language and semantics are not taught as integral to the journalism programme in the country.

Semiotics and symbolism are removed and remote from the consciousness of journalism schools.

And history too is imbuing us with the past tense and a proper sense of what brings us to the present.

And at the same time, be learned on the fleeting present.

This brings us to the first draft of history — that raw, immediate and unprocessed reality captured on site by the reporting function both by the journalist and lay person engaged with social media.

The trained journalist — either by the newsroom or classroom — carries a different lens and a peculiar acuteness in judgment, compared to the so-called citizen journalist.

In this regard, an engagement with literature is critical to the student of journalism and continuously relevant to the journalist. There is a visible lacuna in the curriculum.

But the journalist is not a historian. He is a narrator and a storyteller. And by training, he knows the difference between a deadline and a dateline.

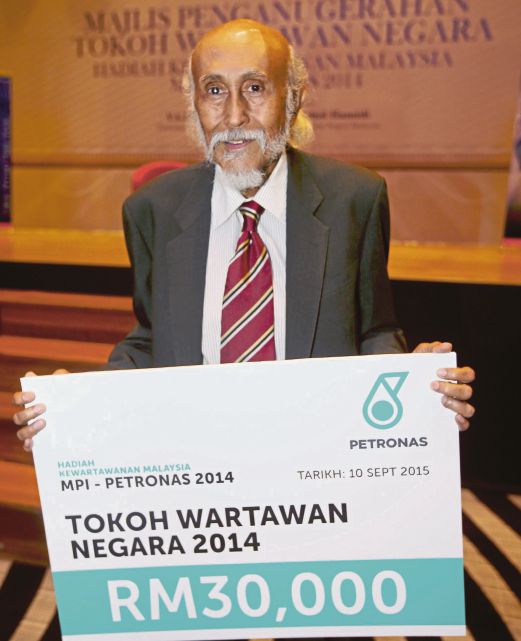

At a recent luncheon in honour of National Journalism Laureate 2014 recipient Datuk Ahmad Rejal Arbee at Bernama, the national news agency chairman Datuk Abdul Rahman Sulaiman made one stark point — journalism trains us on punctuality.

Two other National Journalism Laureates — Tan Sri Zainuddin Maidin and Datuk A. Kadir Jasin — also spoke. Both reflected punctuality through various parables.

The latter two talked about having to find and use a telephone in unfamiliar places for sending their stories to catch deadlines then — before the age of mobile and digital devices. Indeed, punctuality is not only an act (of being punctual), but a thought and a process enabling the fulfilment of that act.

Either in daily life, or in the professions, time is of the essence. But unlike the professional or the academic philosopher, where time is almost always celebrated as a discourse in progress, for the journalist, without deadlines, he can never be a witness in scribing the first draft of history, and what is to become of the nation.