IN September last year, the international legal community was shaken by two seemingly unspectacular cases. Both were brought by plaintiffs against the Dutch government for the government’s failure to protect them in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. Both cases were heard at the Supreme Court of the Netherlands, where a final judgment was rendered.

The reason why these cases created a chill among sovereign states lay in the judgment handed down.

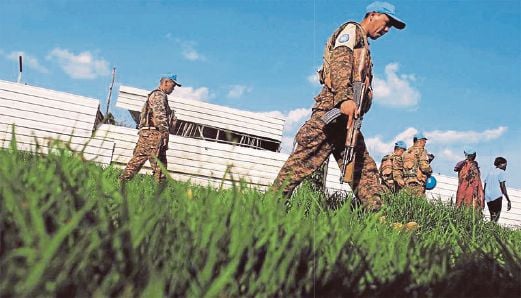

The United Nations has long been established as having absolute immunity from responsibility in peacekeeping cases, at least in the legal sense.

But the two cases in the Netherlands argued that the states’ sending the troops were not immune from the actions of their troops on the ground, and won on this point.

In essence, this now raised the culpability of a state when contributing peacekeepers to the UN. It would mean that states could now be sued for their peacekeepers’ failure to protect citizens in conflict areas.

The facts of the two cases were similar. In the case of Hasan Nuhanovic against the Dutch government, Hasan worked as an interpreter where the Dutch battalion was stationed. He possessed a UN pass, and was on the list of persons who could be evacuated together with Dutchbat. Just before Srebrenica fell, Hasan’s parents and his brother sought refuge at the compound.

In the second case, that of the Mustafic family, it was Rizo Mustafic who was seconded to the Dutchbat compound as an electrician. Rizo, his wife, and two children, sought refuge with Dutchbat as Srebrenica fell.

Both the Nuhanovic and Mustafic families were ordered to leave the compound as the Dutch battalion was evacuating Srebrenica.

Hasan’s family was subsequently slaughtered, and Rizo was executed by the invading Bosnian-Serb army.

All in all, over 8,000 men and children were executed by the invading forces in Srebrenica, making it one of the worst failures of the UN’s responsibility to protect. There were a number of reasons why these two cases were successful in bringing the Dutch government to accountability where others had failed.

FIRST, the action was against the Dutch government, not against the UN. In previous cases, court after court in country after country had upheld the UN’s immunity in peacekeeping missions.

But these two cases argued that it was the Dutch battalion, despatched under UNPROFOR, that was responsible for the deaths. Srebrenica had fallen, thus ending the mandate of UNPROFOR. The Dutch peacekeepers were being evacuated, and therefore, the battalion was under the effective control of their sending state, not the UN itself.

SECOND, the Dutch battalion had received instructions from the UN to enter into negotiations with the Bosnian-Serb army for their evacuation, and to protect the refugees.

It was this last instruction which the Dutchbat had failed to carry out, ushering the refugees out of the compound and into sure death. They had been given express orders not to expel the refugees in their compound, but failed to follow these orders.

THIRD, the families of Hasan and Rizo were among the last to leave the compound. By then, Dutchbat was fully apprised of the fate that awaited the families of the refugees they were turning out.

They already knew that there was a house around 300 to 400 metres from their own compound, where Muslim men were being tortured or even killed. And yet, they decided to leave the refugees to this fate.

Even though the Supreme Court found the Dutch government liable for the loss of the Nuhanovic and Mustafic families, the compensation awarded was paltry at best. Hasan was only awarded costs, while Rizo’s wife and two children received E20,000 (RM87,500) each.

The cases are important not because of the compensation it handed out, but because for the first time ever, a state which contributed troops for peacekeeping missions under the UN banner could potentially be liable for the failure of that mission.

Countries, such as Bangladesh (with more than 8,316 personnel in various UN peacekeeping missions), Pakistan (with 8,250 personnel) and India (with 7,848) are well-primed for similar court actions.

Malaysia, with only 878 troops on the ground, may be safe on the balance of probabilities.

The two cases of Hasan and Rizo are part of the new global recognition of troop-contributing countries’ responsibility and accountability in UN missions. But most of the UN troops come from developing states, not developed states. The highest-ranked Western country in the list of UN troop-contributing countries is Italy, at number 22, with only 1,185 troops, 19 military experts and five police officers.

The ramifications of these September judgments last year are only now being felt around the world. Already, the UN has problems raising enough troops to send, without this added fear compounding the problem.

In April, the “Mothers of Srebrenica”, an association representing some 6,000 victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, brought legal action against the government of the Netherlands citing the Dutchbat’s failure to “prevent the murder of thousands of civilians”.

The association’s earlier action in 2007 failed because of the UN’s immunity. This time around, with the Nuhavonic and Mustafic cases as precedents, it is the Dutch government that is charged with the failure to protect.