DO we actually grow up to become our mothers? You'd be surprised to learn that it can be true.

The notion of growing up to become our mothers isn't just a cliché; it's grounded in psychological and neurological principles. Psychotherapists refer to this as inherited patterns — beliefs and attitudes absorbed from observing our mothers throughout childhood. Our interactions with our parents become the default setting in our brains, shaping how we navigate adulthood, especially during moments of stress or uncertainty.

For some of us, that journey might require a bit more effort.

My mother's frequent exclamation: "You're more like your father!" rings in my ears, and I can't deny the truth in her words. Comparing myself to her, I feel like I've drawn the short straw. While my sisters effortlessly channel her elegance, I seem to have inherited my father's stern expression, fiery temper, prominent nose and a biting sense of humour.

Unlike my mother, I'm hopeless in the kitchen, and let's not even talk about my less-than-neat habits — a stark contrast to her meticulous ways. "Cleanliness is godliness!" she would often remind me and I'd groan inwardly.

My mother has the invisible sorcery of quiet authority, always kind, never needing to shout or threaten. She knew when a hug, a kiss, a cup of hot Milo and comfort were in order and when they should be withheld in favour of stern advice.

Her unwavering faith in God gives her strength, and though she's soft and gentle, her resilience shines through during challenging times. I'm furious with her because I want to be her. Yet, I continually find myself falling short. It's terribly annoying.

It's a strange evolutionary misstep that even the most powerful and noble of all the human emotions can, in any given moment, be trumped by irritation. But really, perhaps this is the ultimate compliment. I can push back and prickle, safe in the cosy belief that all the questions, big and little, still have answers, and that my mother knows what those answers are.

And I try not to think about the unbearable day when she will be gone and I will have to come up with my own answers.

But as I gently hold her hand, I'm struck by the subtle but undeniable connections between my mother and me — like delicate webs woven over time. Though barely tangible, these tenuous bonds affirm our shared essence. We both possess a kindness that runs deep, and we love freely, abundantly, without expectation or entitlement.

Now, I find myself on a journey to embrace more of my mother's legacy. I'm slowly learning how to cook, meticulously noting down her cherished recipes. There's a certain solace I find, much like she did, standing over a bubbling pot of curry on a hot stove.

So perhaps, in the end, some of us do indeed turn out like our mothers, while others, like me, may need to exert a bit more effort. I may never fully mirror her, but I'm determined to try — one recipe at a time.

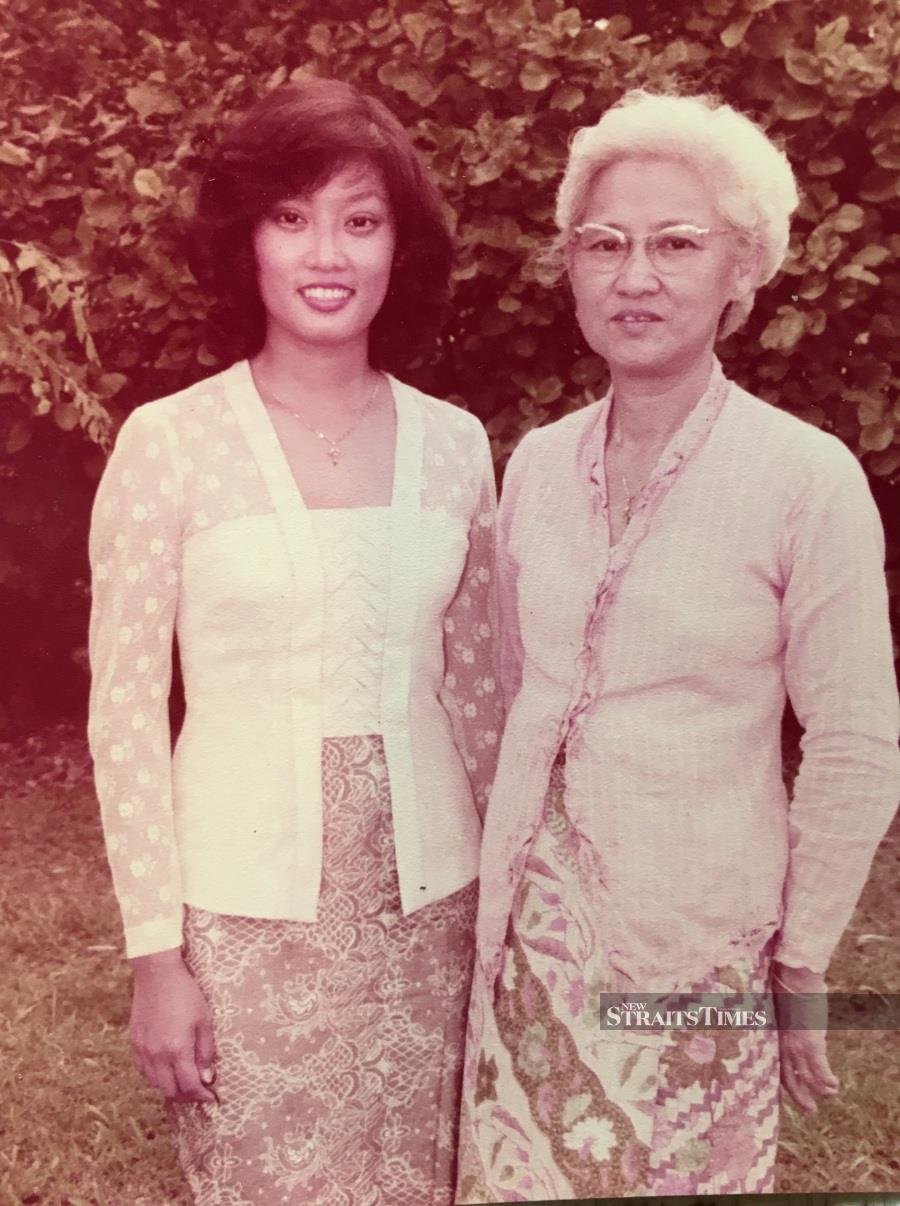

DR LEE SU KIM, author and cultural activist

My mother, a Nyonya from Penang, was an excellent cook. She cooked using the freshest of ingredients and was particular about taste, quality and presentation. Everything has to be seronoh (refined), limau purut leaves have to be sliced so finely they are thinner than the thinnest wires, sambal blachan has to be pounded by hand, even parsley for garnishing has to be cut into tiny, delicate tendrils.

The attention to detail, to a variety of tastes, colours and textures was astounding. It is no wonder she is still remembered fondly today especially for her wonderful Nyonya food, even though she left us more than 2 decades ago. Her method was agak agak (guess-guess only-lah!), a humble description of a philosophy of cooking steeped in intuition based on years of experience, skill and passion.

At 18 years old, I couldn't cook to save my life, but now, I have become a bit like Ma, fussing over the way one cuts the ingredients, using age-old, slow-food techniques to cook traditional dishes, cooking with the same loving passion. She lives on in my memories and the wonderful heritage she's passed on.

ZAHARAH OTHMAN, freelance journalist

In the vault of my memories lies a cherished image: Mak seated on the swing, her eyes fixed on the road, anxiously awaiting my return home on my trusty bike. As thirty minutes slipped by, it was her cue to wrap herself in her selendang, grab an umbrella, and venture beyond the gates in search of me, pedalling home from school.

Mak's propensity for overthinking was legendary, a trait that often tested my patience. Her mind would spin scenarios of accidents and mishaps, fuelled by relentless 'what-ifs'.

Now, in a different time zone, in a distant land, I find myself, a mother to four adult children, caught in the very same cycle that once irked me.

The exasperation I felt as a teenager has softened with time, yet the echo of my mother's habits — sitting with her selendang and umbrella on the swing — resonates within me. Her DNA has woven itself into the fabric of my being over the years.

In today's digital age, I find myself in bed, eyes glued to the screen of my mobile phone. I track my daughter's journey home through a GPS app, watching intently until the car icon turns into her street.

And as I wait for another child to respond to a message, I silently will for the double ticks to turn blue.

While I would have cherished inheriting Mak's skills at the sewing machine or in the kitchen, it seems I've inherited an extra gene — one that undoubtedly annoys my own children!

DR RAVINDER KAUR, scientist and lecturer at Sunway University

My mother, a full-time homemaker with four children, once demonstrated her incredible resilience in a memorable moment. On the day I was born, my sister found her in the kitchen, furiously rolling out her aloo roti chapatis with remarkable determination. She was visibly sweating and kept pulling her kaftan sleeves up, while rolling the dough out and stuffing them with potato masala.

My bewildered sister asked her what was wrong and she replied matter-of-factly that she was in labour.She then declared that she had already prepared 25 chapatis — ample sustenance for the family during her hospital stay.

In fact, she gave birth mere hours later, while my father was busy parking his car!

This anecdote embodies her stubborn yet resilient nature, a trait she has passed on to all her children, including myself. Under her influence, we have become determined individuals, unyielding in our pursuit of goals.

She remains the cornerstone of our family, her strength and determination serving as an enduring inspiration to us all.