THERE'S worldwide wariness at the moment about anything that looks like it might be Russian. Uzbekistan is another matter entirely. Nowadays this large, landlocked country has shaken off the bad publicity of the past and gained some real independence from its former overlord.

Since ceasing to be the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in 1991, this country has put a lot of distance between itself and Russia. One obstacle is the alphabet it uses. Cyrillic hasn't been a good look lately, unless it's being used by Ukrainians. Until the 1930s, Uzbekistan was using the Arabic alphabet. Then the Russians phased it out, like the Jawi-averse British in Malaya.

As part of Uzbekistan embracing the world, it has pioneered a number of cultural initiatives. Above all, there's "The Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan in the World Collections". Seldom has any heritage programme been as comprehensive as this one.

Since 2017, Uzbekistan and its new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, have been single-minded in promoting the past. A remarkable quantity of art has come out of Central Asia and Uzbekistan is far from hoarding this bounty. It wants to share the good news with the entire world as it feels this legacy belongs to everyone.

National pride is also at stake, but it's remarkable how accommodating this country is about the dispersal of its culture. Instead of trying to reclaim everything, Uzbekistan embraces all the wonders that have been taken to every corner of the globe.

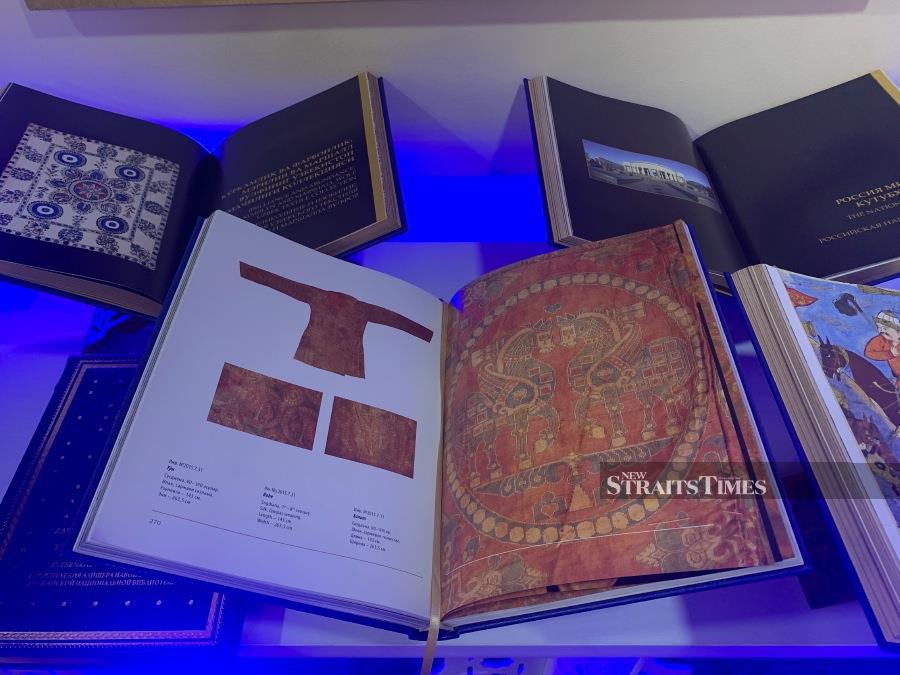

Cataloguing these treasures has become the highest priority. I can't think of any other nation that has asked the world to join such a project without angling for some restitution. So far, the outcome has been some rather splendid "book-albums" as they're officially described.

Backing up these compendiums of artefacts held overseas are facsimiles of manuscripts that have been scattered throughout numerous libraries. And then there are the television shows and translation undertakings that have been happening unobtrusively.

SHARING UZBEK ART

To make the enterprise more relevant to Southeast Asia — and a possible inspiration for what could be done with regional heritage — the 5th International Congress of the World Society brought participants from 40 countries, most prominently Malaysia.

This took place in Samarkand, where the first such congress took place in 2017. The theme then was "The Way to Dialogue between Peoples and Countries". Since then, it has been held in different locations, including St Petersburg. Sadly, happening in Putin's hometown doesn't seem to have stopped him exerting Russian cultural expansionism at the expense of Ukraine.

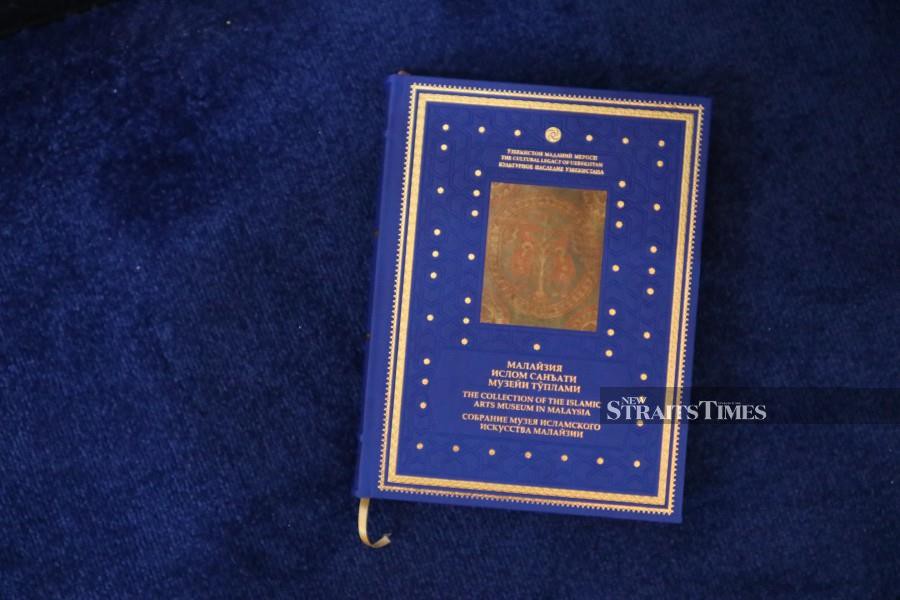

More recently the congress was back in Samarkand. The latest book to accompany the scholarship is from the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia and is dedicated to sharing Uzbek art with the world. It's not surprising that the agencies involved were so keen to collaborate with Kuala Lumpur's most internationally inclined museum. There's a great deal of relevant material on display. One answer to the question 'where can I see these Uzbek wonders?' is the Malaysian capital.

The first port of call should really be Uzbekistan itself. Samarkand and Tashkent have a magical reputation for a reason, and it's a lot easier to get there these days. Malaysia Airlines recently signed an agreement to ensure this. There's also the book to peruse.

Alternatively, there's the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia on your doorstep, replete with 200 works of art from Uzbekistan. More than that, the building has featured Uzbek artistry since the very beginning.

Way back in 1997, when the Lake Gardens site got going, it had already been arranged that Uzbek master craftsmen would travel to Malaysia to create the five sculpted-plaster domes that are among the building's focal points.

GOLDEN AGES

The main attraction is, of course, the collection. Unless you go looking for them, Uzbek works rarely stand out for being labelled "Uzbek". When you see names like Samarkand attached, then you know that you're beholding the output of a civilisation that has had multiple golden ages.

There are so many contributions to the world of aesthetics made by the empires that have come and gone in that region. For me, there's few that can beat their ceramics. More than a thousand years ago, Uzbek potters were creating designs, often on quite humble eating utensils, which have the power to engage audiences centuries later. The calligraphy on these earthenware dishes tends to be simple blessings such as "good health to the user", but their impact has rarely been surpassed.

Even earlier that these Samanid-dynasty wares, the land that is now Uzbekistan was sharing in the greatness of a trade route that has become legendary. The Silk Road passed through, bringing sumptuous trade items, not least of which was silk.

For a real masterpiece of couturier wear, what could beat the Sogdian robe shown here? Carbon-14 dated to the 7th-8th centuries, it's from a time when Islam had just arrived in Central Asia. The oasis towns were a magnet for the world's finest wares, which were traded along a route that really extended from Japan to Venice. This garment would have been the pride of any wardrobe.

Many centuries later, Uzbekistan became renowned for robes that were less illustrious, but just as visually striking. These silk garments, worn by men and women of Central Asia, are made from ikat, which is as different from the delicate sobriety of Malay ikat as can be imagined.

They're filled with colours and compositions of hallucinogenic intensity. You won't catch the likes of Oscar de la Renta appropriating local limar, but he and many others went all out with their Uzbek borrowings. To complement these extraordinary textiles are pieces of jewellery so huge and imposing, pieces seem too small a word.

Topping off all these tangible temptations for the senses are embodiments of the mind and the spirit. Uzbekistan has produced more than its share of great thinkers, physicians, scientists and religious scholars.

These range from the Observatory of Ulugh Beg (in Samarkand) to housing what might be the oldest extant copy of the Qur'an (in Taskhkent). Variety has always been the spice of life on this section of the Silk Road.

Follow Lucien de Guise at Instagram @crossxcultural.

Apply AirAsia Promo Code to enjoy huge markdowns on Uzbekistan flights.