"BANG!" And before I knew it, blood was streaming down my hand.

I started the Chinese New Year literally with a bang. I was playing with firecrackers with my brother, Wai. Fortunately, I didn't lose any finger.

Our parents, relatives and neighbours would all be in a jovial mood during the Lunar New Year, the biggest festival and holiday celebrated by the Chinese.

In the 1960s, lighting firecrackers was a common way of celebrating CNY. On its eve, there'd be loud explosions of firecrackers throughout the night, making it quite impossible to sleep.

Many shops would light a long chain of firecrackers and they could last for several hours. The whole street would be covered with red pieces of paper from the firecrackers. It was literally a red carpet welcome for the new year.

Wai and I loved to play with firecrackers under some shady mango or rambutan tree. We'd light them under a coconut shell or a Milo tin. The explosion would catapult the shell or tin to the branches above. Some fruits would fall as a bonus for our effort.

However, sometimes, no fruits fell except some angry and fiery red ants. Nonetheless, red ants were also considered as good omen as red was an auspicious colour.

As children, we were happy as we got to receive ang paus and eat our favourite cookies.

Superstitions abound during the CNY. Almost everyone will wear red as it symbolises good luck and tidings. Incidentally, the famous golfer, Tiger Woods, wears red during a major tournament, apparently at the insistence of his Chinese mother.

On the first day of CNY, nobody will be allowed to cut or wash their hair or even shower.

We are also not allowed to sweep or clean our house. Doing so will bring bad luck. We couldn't use any expletive either — a rule some of my friends find hard to follow!

The Lunar New Year is celebrated in many countries throughout Asia. The most important meal is the annual reunion dinner with family members at home.

Before the pandemic hit, the balik kampung exodus or the annual mass migration exercise will ensue, involving millions across Asia as they rush back to their hometown. This often resulted in massive traffic jams.

In some countries like China, Korea and Vietnam, thousands would be queuing overnight for their train tickets home.

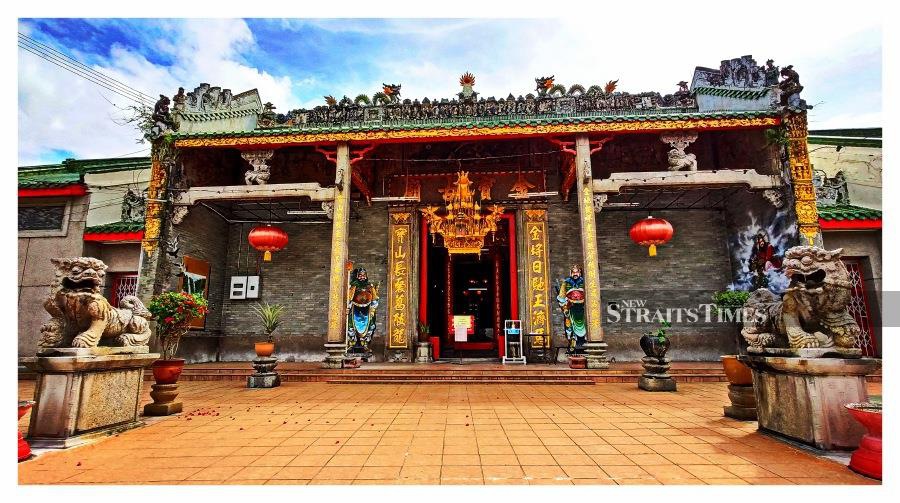

OF TEMPLES AND SCARY GUARDIANS

The practice of Chuen Wan, or changing one's fortune, was popular among the Chinese back in the 1960s.

They'd visit the temple on the eve to pray for good luck and health.

My father would bring Wai and me to the local temple to pray too. For sure, it was a scary experience for a six-year-old.

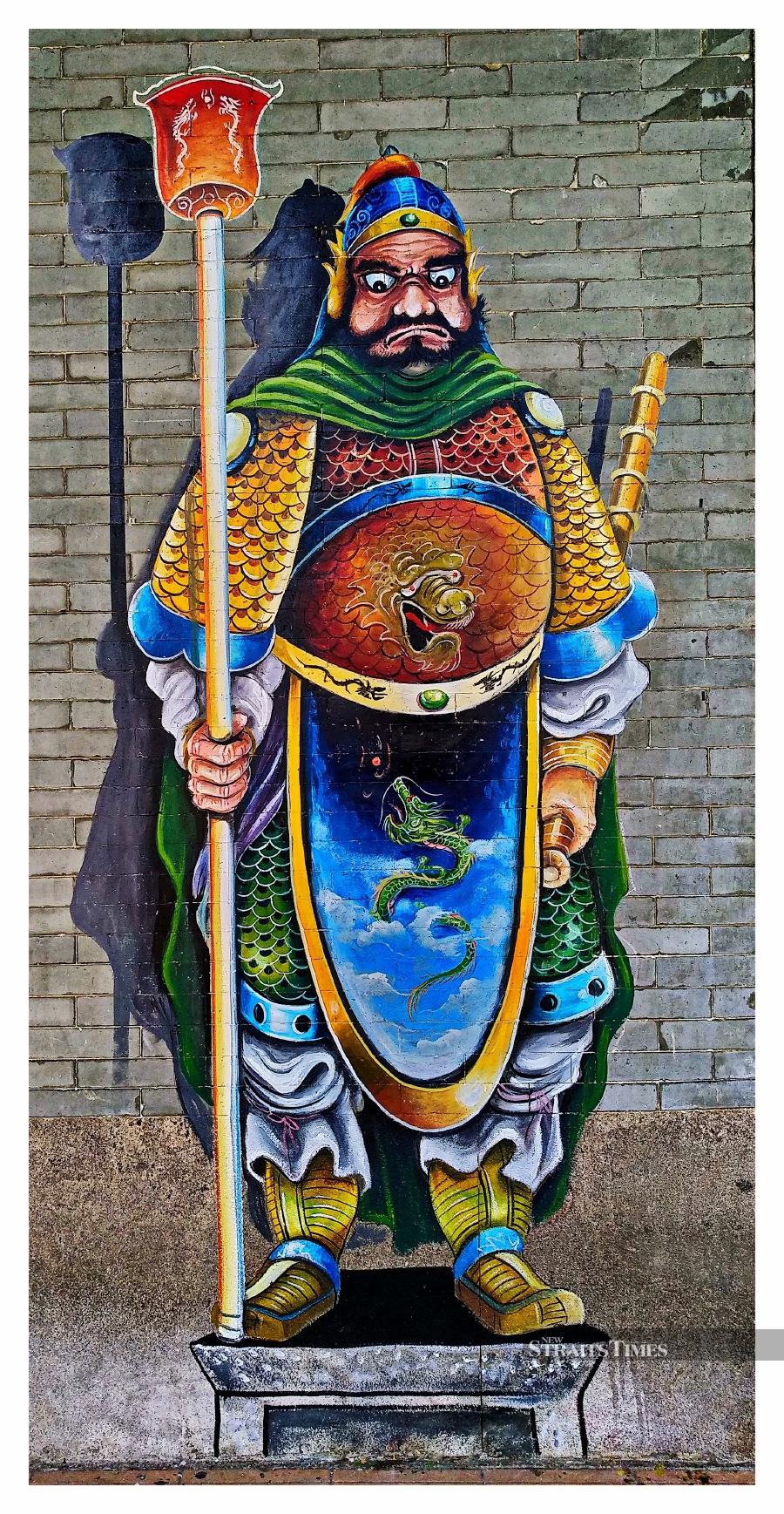

Some of the gods had big protruding eyes, long red tongues and sharp canines.

I guessed they needed to look really fierce to chase away the evil spirits.

The lion dance would always be quite entrancing. I'd watch in amazement as they executed acrobatic jumps on high stilts in tempo with the loud drums, gongs and cymbals.

At the temple, Wai and I would help our father light up some candles and joss sticks. Some of the joss sticks there were really big and long. I figured it would take a few days to finish burning them.

The Chinese believe that if the smoke reaches the heavens, the gods would then bless them. Often, the temple would be so stuffy and smoky that our eyes would water

Given my father's meagre salary, we could only afford half a chicken, some local bananas and rice wine as offerings for the gods to wine and dine during Chinese New Year.

However, I noticed some richer folks would offer expensive French brandy as well as Havana cigars for the God of Luck/Prosperity.

I learnt later that many worshippers were praying for the lottery numbers for the weekend draw.

I did wonder whether that amounted to bribing our puritan Eastern gods with decadent Western goods. It was an eye-opening lesson for me in bribery and corruption, involving even the gods in heaven.

After praying to the various gods, my father would instruct my brother and me to walk around the altar table three times for the Chuen Wan tradition.

With the large crowds holding out their big bundles of burning candles and joss sticks, it was a hazardous mission for us.

To avoid all the smoke and crowd, we'd hide under the altar table instead. We'd only emerge after a few minutes to look for our father.

Upon seeing us, father would be delighted, thinking that we had obediently completed our three rounds. He'd then treat us to our favourite iced kacang.

One of the more popular practices with the worshippers was something known as Cao Chim. They'd kneel in front of their god and shake some small bamboo strips with some messages in a container.

For a fee, the temple priest or caretakers would help the worshipper to interpret the message. So, the priests and caretakers also acted as gatekeepers to heaven.

TRADITIONS GALORE

A few weeks before CNY, we'd help our mother make our favourite kuih kapit (also called "love letters").

We'd pour the batter and squeeze them in a mould. The timing had to be perfect in order to obtain the nice golden-brown colour.

Any extra batter oozing out of the mould was never be wasted. These charred bits were crunchy and yummy.

Our "love letters" were delicious as we'd always put our love into making them. Many neighbours would buy our love letters for their celebrations.

The seventh day of CNY is believed to be the birthday for all humanity. Traditionally, the Chinese would mark this occasion by eating yee sang.

In Malaysia and Singapore, everyone celebrates the Lo Hei dinner by tossing, toasting and making loud wishes as they mix the ingredients with their chopsticks.

The colourful, auspicious and delicious ingredients symbolise good luck, health and prosperity.

The addition of salmon and red wine have become increasingly popular for their symbolic and nutritional value.

Meanwhile, the ninth day is the birthday of the Jade Emperor. Hokkien folks would celebrate with special red tortoise buns and miniature pagodas.

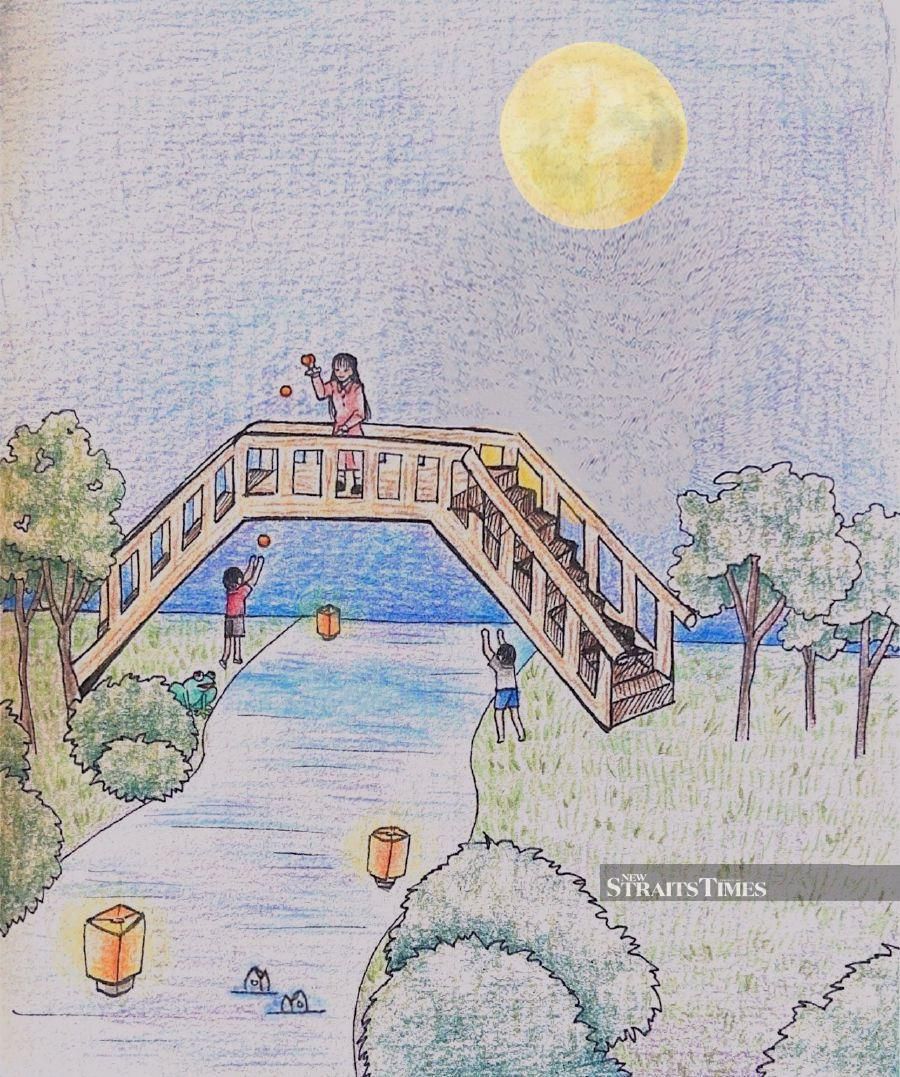

The last and 15th day of CNY is known as Chap Goh Mei — the Chinese equivalent of Valentine's Day. The full moon and display of lanterns never failed to add an air of romance and sentimentality.

Young women would throw oranges into the river from a bridge. It's said that by doing so, the gods would bless them with a rich and handsome husband.

I remember Wai and me standing under the bridge that evening. However, there were neither young women nor oranges for us.

GRAPPLING WITH GREETINGS

Every year, we'd look forward to visiting our grandparents' home near Ipoh during CNY.

We'd bring along traditional goodies such as mandarin oranges, nian gao (literally "year cake") and, of course, our hand-made "love letters".

This was an annual affair which often saw a gathering of scores of relatives. So it was a noisy occasion with many ang paus given out and received.

Our ang paus would normally be just 20 sen. It was enough to buy a dumpling or bowl of noodles then. My sister once received a RM10 note from grandma.

I remember wondering whether it was favouritism or cronyism. I had to earn my 50 sen ang pau by wrapping and rolling a big box of tobacco cigarettes with red paper for grandma!

As a strict Cantonese matriarch, grandma would make all her grandchildren queue up to greet our relatives seated around a large hall. We had to greet them one by one according to their title/honorific and hierarchy.

Remembering all the different orders and titles was quite daunting.

For instance, our paternal third aunt would be Sam Ku and sixth grand aunt, Lok Poh. If they happened to sit beside each other, it would then be "Sam ku, Lok Poh", which actually meant "busy body" in Cantonese.

Our grand uncle would be "Pak Sook Koong", which sounded like a centipede. Our paternal fifth uncle was "Ng Sook" which appeared as "not smelly". However, there was another "Chow Sook" which meant "smelly uncle".

As children, we also needed to remember lengthy greetings. One of the popular wishes was Loong Ma Jing Shen. It oddly literally meant "Dragon Horse Spirit Good". However, its real meaning was "Wishing you good strength and spirit".

Another fishy greeting was "Lin Lin Yao Yue", which literally translated is "every year got fish". It actually meant "Wishing you abundance every year".

The different honorifics and greetings came with different intonations and connotations. Although they could be quite funny, grandma was always in no mood for humour.

If we could not remember the titles or greetings properly, there'd be a nasty reprimand instead of ang paus. Perhaps this was her way of instilling the strict Confucian tradition in us.

After the lengthy greetings and ang paus in the morning, everyone would be hungry. The traditional lunch would comprise a hearty and happy affair with everyone seated around the table.

The adults would be busy feasting and drinking with endless rounds of "yum seng".

After lunch, the adults would play mahjong on their high tables while the kids would indulge in card games on the floor.

Gambling is perhaps inherent in the Chinese genes. There's a saying that once a child could start counting, he'd start gambling!

Incidentally, a common greeting during CNY is "Gong Hei Fatt Choy!" Its emphasis on luck and prosperity over health and stability predisposes the Chinese to a life of risk-taking.

TO A BETTER YEAR

Over the centuries, millions of Chinese had taken huge personal risks to seek greener pastures overseas.

In the 19th century, many thousands migrated to Malaya to work in the flourishing tin mines of Kinta Valley.

These pioneer tin miners helped to build the early foundation of the Malayan economy. They created thousands of jobs and generated untold revenue for the government.

Besides being successful, many were also philanthropists who had donated millions for the benefit of all races in Malaya.

Among the most generous and far-sighted leaders were Lee Loy Seng, Foo Choh Choon and Leong Sin Nam.

Their generosity, volunteerism and public-spiritedness touched the lives of millions. Their selfless and tireless altruism were inspirational. Their contributions are remembered in the roads named after them in Ipoh today.

According to the Chinese zodiac, this is the year of the Ox. For centuries, the ox works hard in our padi fields to feed us. By contrast, the rat symbolises disease and theft.

That's probably why the Covid pandemic started last year with all its attendant problems. Let's hope and pray that the Ox will chase away the Rat and bring a much-anticipated recovery, stability and prosperity for our world soon.

Gary Lit Ying Loong, a retired academic from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) Singapore, is presently a Visiting Professor at some universities in Asia and Europe. Reach him at [email protected].