IT was history in the making, sealing the golden age of Malaysia Airlines. What was to be a simple delivery service of an aircraft from the Boeing factory in Seattle to the other corner of the world — Malaysia — became a record-breaking feat, covering over 20,000 kilometres in 21 hours and 23 minutes.

At 10:11am on a Tuesday morning, the familiar Malaysia Airlines livery painted on the brand new B777 glimmered in the bright morning sun as the plane touched down in time to celebrate Malaysia Airlines 50th anniversary celebrations.

The 777 refuelled at the airport, and then departing at 12:15 pm, the team of pilots flew non-stop to Seattle over a record-charting period of 18 hours and 39 minutes.

The flight set new world records for longest flight and fastest round-the-world flight by a commercial airliner, with a total flight time of 41 hours 59 minutes over a distance of 37,514 kilometres.

Seated behind the cockpit for both flights, 36-year-old Captain Izham Ismail was greeted with much fanfare in both countries.

Flashing a grin at the cameras, the diminutive pilot remarked to reporters: "To be able to fly an aeroplane in 42 hours, circumnavigating the world and the Tropic of Cancer... to me it was very interesting and something to remember for the rest of my life."

Twenty-three years have passed since then and much has changed for the affable pilot since his record-breaking feat. For one, he's hung up his epaulet and had taken over the helms of Malaysia Airlines since October 2017.

For another, he's been hard at work navigating the beleaguered national airlines out of turbulence since he stepped into the role of what's been billed as "the toughest corporate job in Malaysia".

It was quite the coup to land this interview with the reticent chief executive officer of Malaysia Airlines. He's media-shy, preferring to let his actions do the talking. Much has been written about the airlines, but the captain himself had managed to evade the pervasive spotlight that came with the job description.

"So what do you want to know?" he wastes no time in asking me pointedly as he takes his seat next to me, eyes glinting behind his glasses.

A little older and greyer from his jubilant appearance during his fateful flight in 1997, the slim-built man who remains remarkably youthful in his immaculate "corporate" uniform comprising a suit-and-tie, gazes at me appraisingly.

Our conversation opens with his fateful Seattle journey and he visibly relaxes. He was posted to Seattle at that time when Malaysia Airlines was expanding vigorously. The aircraft the airline purchased was ready for delivery and they were planning to ferry it back to Malaysia.

As Izham was going over the numbers with Boeing's chief test pilot Joe MacDonald, he remarked casually: "Hey Joe! This aircraft can actually fly around the world!" MacDonald agreed, replying: "That's a fantastic idea! Maybe we should do this!"

"It was a crazy idea but they went with it!" he recalls, shaking his head in disbelief. The rest was history. The first leg of the flight, he explains, beat the record of the longest flight on air while the second leg beat the fastest record on a single flight.

"Back in those days, we didn't have the kind of mobile phone cameras that we have today," he says regretfully. No pictures were taken but his memories remain as vivid as ever.

"Remember the comet Halle-Bopp?" he asks animatedly, leaning towards me. "It passed right on top of us!" he exclaims, grinning. With daylight on the left of the aircraft, night-sky on the right and the comet streaking across the two time zones, time stood still for Izham and MacDonald who were manning the plane.

"That's something I'll never forget," he murmurs leaning back. "And I realised then, how small and finite we actually are in this whole entire universe. That was the time I really landed on my purpose on what I wanted to do."

As fate and luck ("Depends on how you look at it," he remarks drily) both converged, Izham soon found himself on another fateful trip — commandeering the national carrier as chief executive officer.

His trajectory to the upper echelons of Malaysia Airlines was one of two trips Izham admits to have never planned on piloting.

STAYING GROUNDED

The first of course, was the fact that he never wanted to be a pilot in the first place.

"I wanted to be a civil engineer. I wanted to build bridges," he admits ruefully. He took on the job as a cadet pilot, realising it was the quickest way to earn money to support his family.

"I was born poor," he readily admits. A child of mixed parentage — something that was frowned upon back in the day — Izham's family soon found themselves shunned by both the Malay and Chinese communities in his village.

His Chinese mother turned to entrepreneurship to support the family. From peddling nasi lemak and kuih to jual kain (selling clothing material), she worked tirelessly to put food on the table.

Money and food were scarce in their little attap house at Jalan Kampung Perak, Alor Setar. "I'd keep the money I earned selling nasi lemak before school, and would go hungry during recess," he recounts candidly.

To curb hunger pangs, he'd drink water from the nearest tap to fill his stomach. "I tasted poverty," he says softly, adding: "I realised from early on that education would be my lifeline to get out of being poor."

He studied hard enough, securing a scholarship to study marine engineering in England. But his sisters had other plans for him, having quietly applied on his behalf to join the national airline.

"I was set on pursuing my studies but my sister begged me to go for the interview. She realised this would be the fastest way to earn a decent living for the family," he recalls.

Out of 3,700 applicants, Izham was one of the seven chosen for the two-year fast-track programme.

"I didn't expect to succeed and didn't even know what the job entailed. Fly planes? Okay sure. My starting salary was RM150 — a princely sum to me at that time. I realised that my ambitions to further my studies had to wait. I needed to support my family first."

Looking back, he's grateful for the opportunity that Malaysia Airlines extended to him.

"The organisation paved the way for me to get my family out of poverty," he shares. It took him five years to achieve that.

Izham left for the Philippines for his pilot training. In the meantime, his mother kick-started a business that finally paid off. Any Kedahan, he tells me proudly, would've heard about Kuah Rojak Mak Bee. "That was my mother's business," he pronounces, smiling.

He sent money back dutifully. But somehow — despite a thriving business back home — money was never enough.

"I'd often go back and advise her to stop working. I wanted her to rest and be cared for but she wouldn't hear of it," he recalls. He puzzled over her lack of money but it was only in 2004 did he get his answer.

"I was in South America when my mother passed away. I flew back to her grave," he recounts regretfully. His younger sister recorded the funeral and he was astounded to see the crowd that gathered at his mother's burial.

They showed up in tears, lamenting: "Mak Bee tak boleh mati! Mak Bee tak boleh pi! Siapa nak bagi beras? Siapa nak bagi gula? Siapa nak bagi duit? Siapa nak bagi makan?" (Mak Bee cannot die! Mak Bee cannot go! Who will give us rice, sugar, money and food?)

"I realised she needed money from me every month because all income generated from her business was channelled back towards the community!" he says emphatically, eyes glistening behind his spectacles.

On her deathbed, she'd instructed his sister to carry on with the business. "Hang janji dengan mak, hang jangan ambil sekupang pun!" (Promise me that you'll not take a cent from the business). Those values, he says, he held close to his heart. "To always give back to the community."

On that record-breaking historic flight, Izham was reminded of his mother's legacy.

"It was time for me to give back, and that was my purpose," he reveals, adding: "Doing this job isn't for fame or money. It's first and foremost to repay the kindness this organisation extended to me and my family all those years ago. It gives me the opportunity to help people and replicate the values my mother instilled in me."

TAKING OFF

The father-of-three grew to love the job entrusted to him. By his own frank admission, he rose to become a "… great pilot".

The lack of a university degree somewhat bothered him, so he continued to pursue knowledge.

"I self-studied a lot!" he reveals. A voracious reader, he'd spent countless hours browsing through books at bookstores, devouring a wide range of subjects from business, history to economics.

"I tried to finish a book every weekend. That was my rhythm," he shares. Read any fiction? I ask. "Tom Clancy," he replies, grinning.

In just 10 years after joining Malaysia Airlines, Izham's leadership capabilities were recognised. He was quickly earmarked for leadership and was soon appointed to a management position in 1990.

"I was fortunate to have been handpicked and given many portfolios over the years. I was moved from one position to another every two years."

The only job he has never experienced was Human Resource. "On hindsight, I wish I'd garnered more experience there. Eighty per cent of this position today requires me to rally people!" he says, sighing.

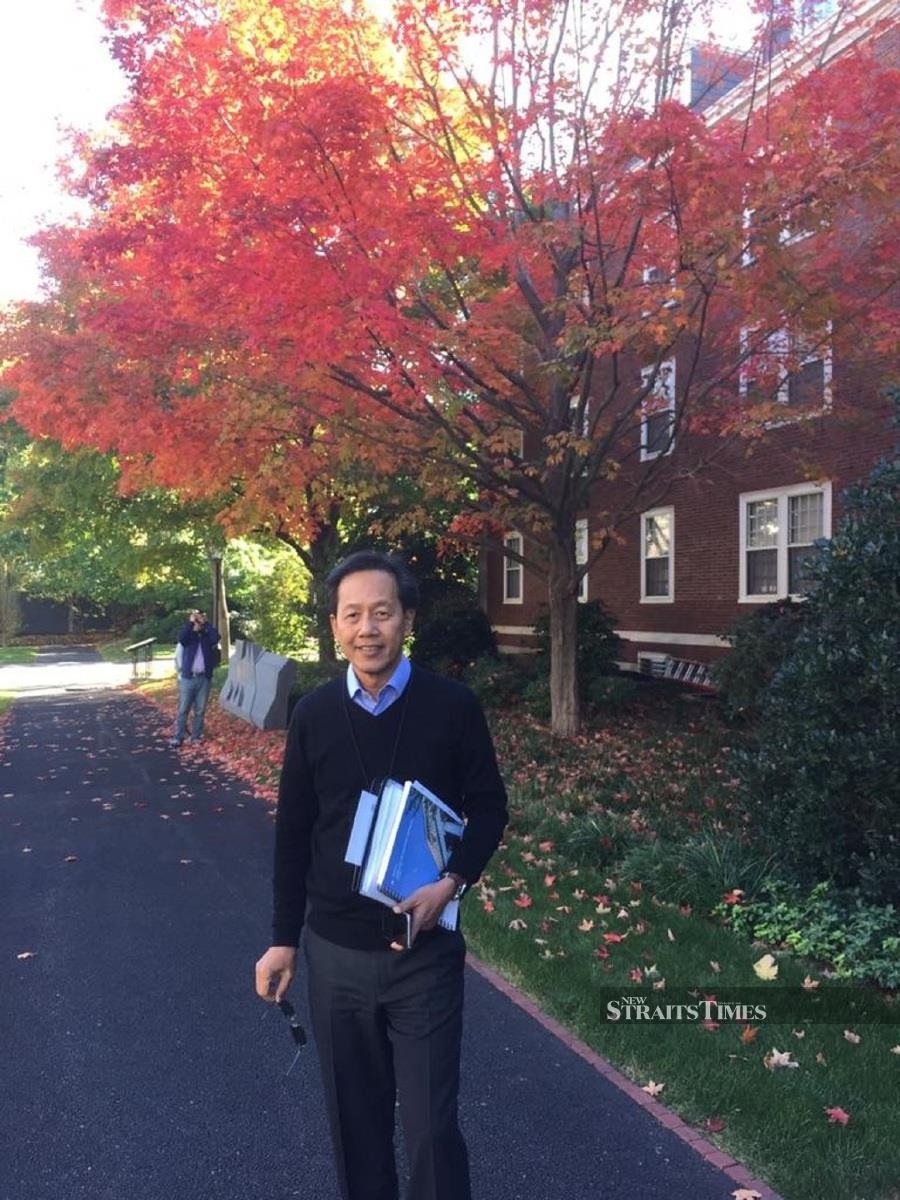

In the course of grooming him to take on leadership roles within the airline, Izham was sent to business school at Harvard University for an advanced management course equivalent to a Masters qualification.

"I was finally getting my chance to study at a university," he says, smiling. He remembers having cold feet at the thought of going back to school. He called his daughter who reminded him: "This is a chance of a lifetime. You've always wanted to go to university!"

In 2014, his leadership was put to the test. It was the worst year in Malaysian aviation history where two airplanes were lost within a space of four months.

"MH370 brought the airlines to its knees," he admits candidly. "The entire crisis wasn't handled well, being practically run by other stakeholders. It wasn't how you manage crisis communications."

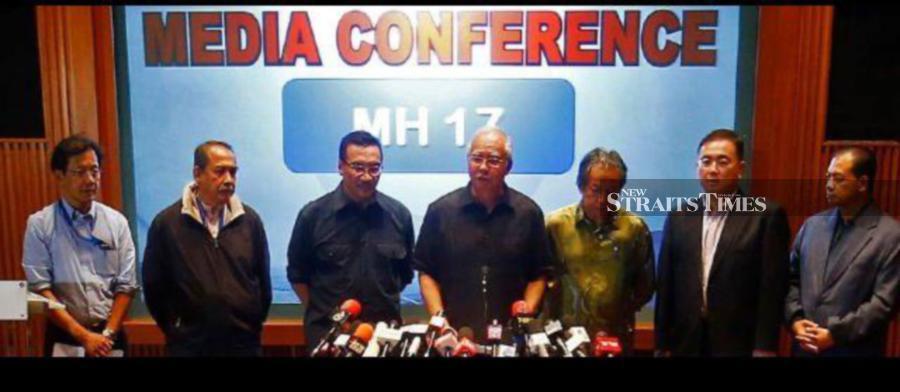

Four months later, the unthinkable happened with MH17. Izham took control of the wheel during the second tragedy. "The loss of human lives was incomprehensible," he says softly. "We'd never be able to recover from that. But we managed to handle the crisis better by learning from our past experience just months before."

Still, it spelt the death knell for the struggling airline. "Everything collapsed and we were looking at billions in losses," he says, adding: "After MH17, MAS as we knew it was gone. It was time to press reset."

When the call finally came three years later for Izham to take on the position of chief executive officer, he was understandably reluctant.

"I'm just a pilot!" he protested to the-then chairman who retorted: "We need a pilot to steer this company. This isn't a request. This is an instruction to put your name to the board."

Izham took on the role as chief executive officer in 2017, the 18th role he's taken on in Malaysia Airlines Group.

CHARTING THE COURSE

It was an unenviable position by his own frank admission. He was immediately saddled with legacy issues; inheriting an ailing airline still reeling from a disastrous 2014, with huge losses racked up coupled with low morale and a loss of direction.

"We needed to get our act together," he remarks bluntly. To rebuild took tenacity, a trait he says he inherited from his late mother. Difficult decisions needed to be made. It wasn't easy to convince everyone to be on board and work towards rebuilding the airline.

Izham sent out a strong message to his senior management: "If you don't believe in this journey, if you have no stamina in carrying out your responsibilities, don't expect to achieve success. Don't bring down your team along the way. You either get onboard or get out of the way."

There were quite a number of resignations and painful sackings that year. "I weeded out non-performers," he says, adding: "I wasn't there to warm my seat. I needed to surround myself with new talents regardless of race, religion and creed."

He believes in celebrating meritocracy, and we can only do that, he says, once we embrace equality in race, gender, background and age.

Before the year ended in 2017, he laid the foundation of what the airline was going to be and where it should be — realigning Malaysia Airlines' purpose as a bigger group — the Malaysia Aviation Group.

Shares Izham: "Malaysia Airlines Berhad is the core business, but each sister company plays a critical role in shaping Malaysia Airlines Group. MAG is a Malaysian business that must make a bigger and deeper difference for Malaysians and Malaysia."

At the end of 2018, the airline narrowed its losses as compared to the previous year. By 2019, the airline was well on its way to recovery. Then the pandemic happened.

The outbreak plunged the airline industry into chaos with passenger flight revenues all but wiped out.

In late January, he activated the Code Yellow in light of the outbreak. The airline increased its alert level and the Emergency Operations Committee (EOC) stepped in to ensure that operations remained smooth while upholding the highest safety standards.

"Every action we took was with the intention of safeguarding our crew, ground staff and passengers," he emphasises.

For the Group, the impact of Covid-19 surpassed the horrific year 2014. "That should give you a perspective on the gravity of the situation," he adds frankly.

He confesses to sleepless nights looking at profit and loss statements. "Those are the times when I really miss my flying days!" he quips. He told his staff that he was going to do everything possible to protect them. All they needed to do was be with him during this crisis.

There were times, he confesses, to stepping out of his seat and trying to imagine what his mother would have done. "I believe she'd have wanted me to help as much as I can possibly do."

He decided that all senior management including himself take a pay cut, to help support staff directly impacted by the pandemic. They agreed. "This solidarity brought us closer as a family," he says proudly.

The steely-eyed captain pauses before concluding: "Everything happens for a reason." What's the reason? I ask. "I don't know," he responds honestly. "Let's go through this journey."

For Captain Izham, the long-haul flight isn't over yet. As long as he's handling the controls like a seasoned pilot, you can be sure he's able to see farther ahead and gently navigate Malaysia Airlines to safer grounds.