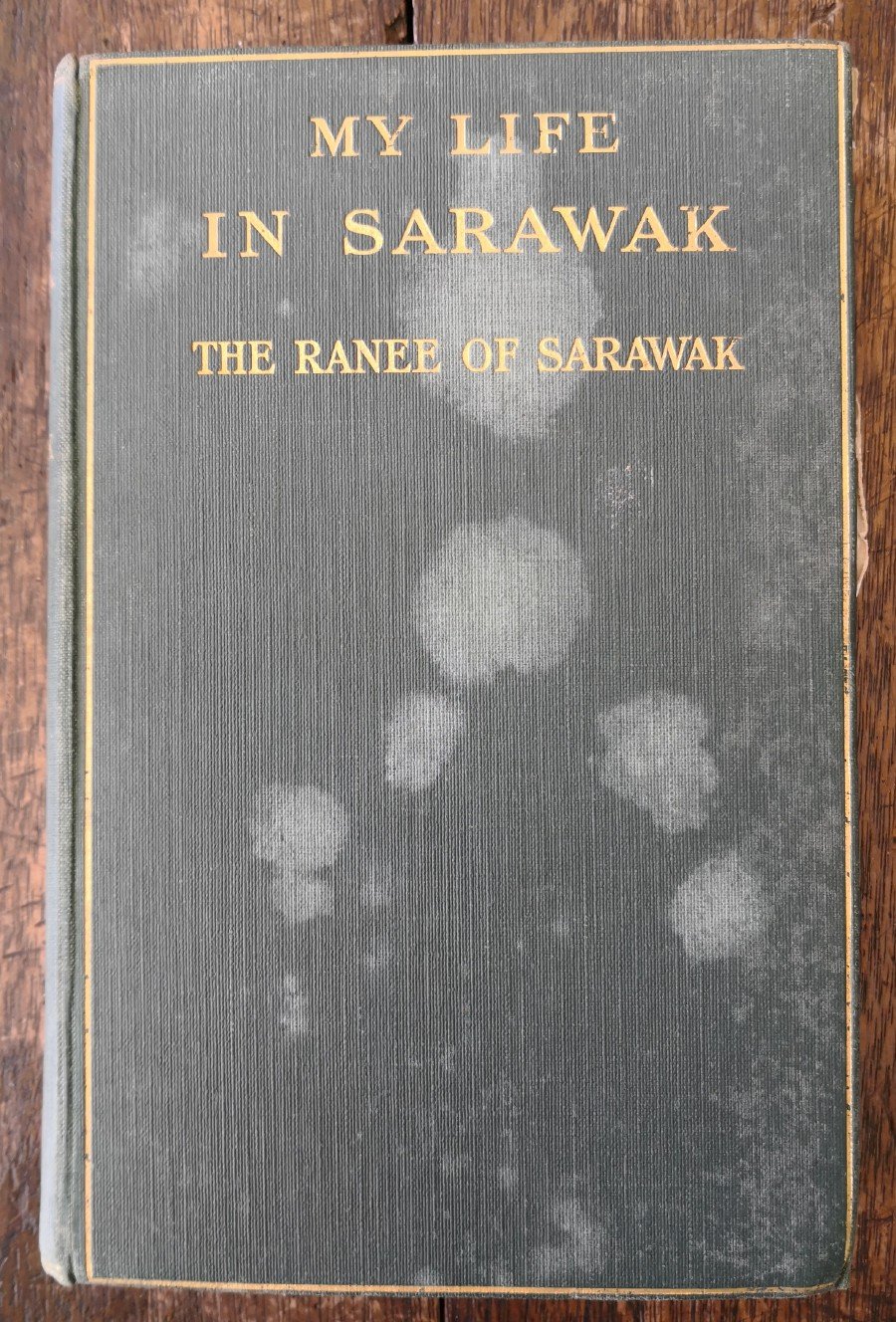

“MOTHER of Sarawak. That was the honour bestowed by the locals upon the Ranee during her reign in the sprawling Borneo state,” my friend remarks when I happen to come across an interesting century-old book while helping to pack an entire bookcase of precious books for his move to Kuala Lumpur. “Her memoir, My Life in Sarawak,makes for an interesting read as it gives a rare insight into her thoughts and experiences while in colonial Borneo,” he adds.

My friend piques my interest when he continues: “She arrived as a young Victorian bride after marrying the most powerful man in Sarawak, the second White Rajah, Charles Anthony Johnson Brooke. At the beginning, she greatly disliked the place but soon she began making friends with the local women and embraced their cultural lifestyle. Thanks to her generous and caring nature, Sarawakians warmed up to her strength and intelligence. At times, she even enjoyed greater influence than her husband.”

Setting the book aside for further scrutiny, I join my friend in setting about the task at hand. With a long list of titles written by famous colonial era administrators and writers like Frank Swettenham, J.M. Gullick, R.O. Winstead, H.N. Ridley and Alistair Lamb, we meticulously bubble wrap each book individually before placing them into storage boxes.

The collection is so large that we only reach the half way mark by lunchtime. Eager to start on the book written by the person who was once an English subject as well as an Asian monarch, I decide to stay on while my friend goes out to pack some food at the nearby hawker centre.

WHO WAS SHE?

Born Margaret Alice Lili de Windt on Oct 9, 1849, she was the daughter of Captain Joseph Clayton Jennyns de Windt, of Blunston Hall, and Elizabeth Sarah Johnson. Like most girls in the mid-Victorian period, Margaret received limited education which included music, dancing and lessons on two to three European languages.

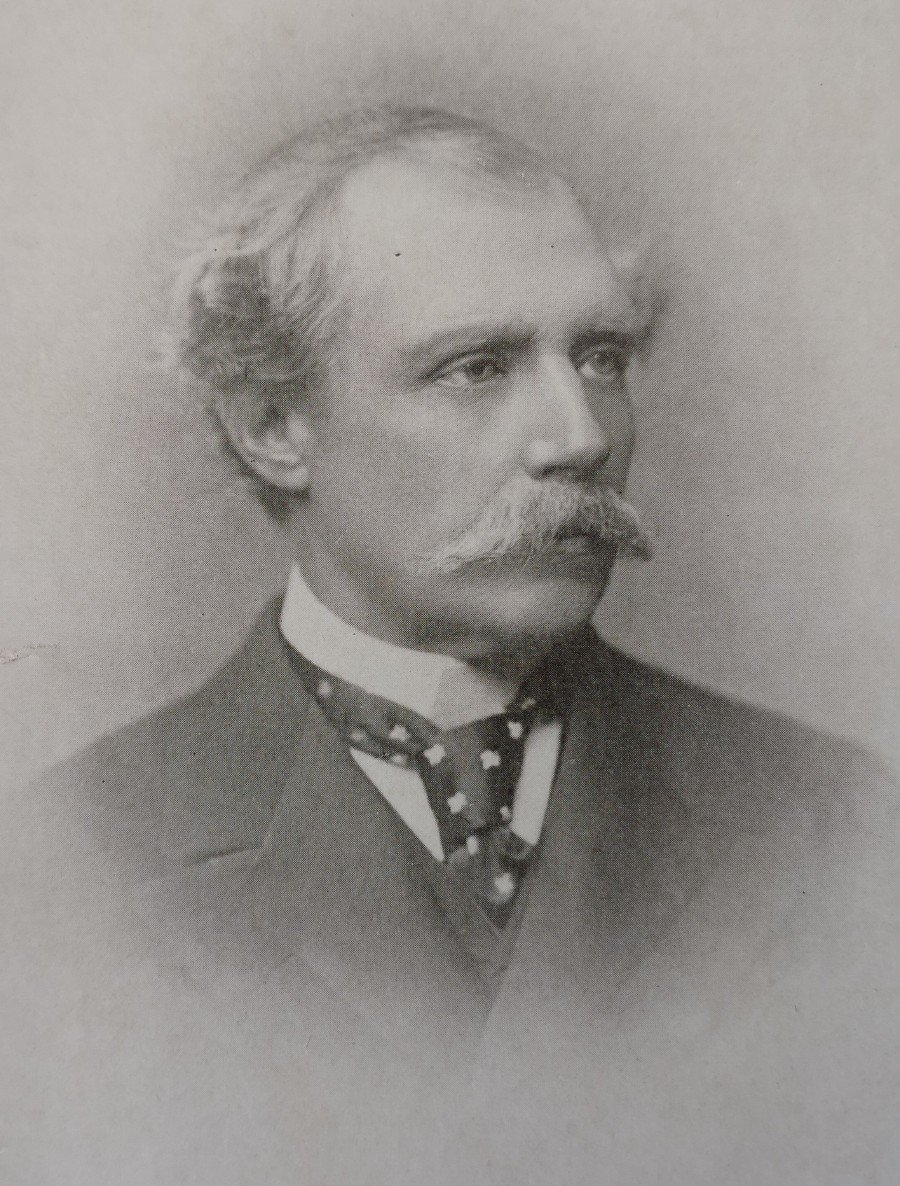

Margaret was introduced to Charles in 1868 when he visited her mother who was his cousin. At that time, James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak had just passed away and Charles, as his nephew and successor, had returned to England in search of a prospective bride to solve Sarawak’s succession quandary.

After a year-long courtship, Margaret married Charles at Highworth, Wiltshire on Oct 28, 1869. After the nuptial, she assumed the title of Ranee of Sarawak, becoming the first woman to hold this position as the previous Rajah was unmarried.

The couple made their first trip to Sarawak together a few years later. Unaccustomed to sea voyage, Margaret suffered constant seasickness from Marseilles to Singapore. She was relieved each time they disembarked at ports cities along the route like Aden, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Penang.

During their brief stay in Singapore, the couple received invitations from the Governor and prominent residents in the colony. It was at one of these functions that Margaret got the opportunity to taste tropical fruits. While most of them were pleasant, she described the soursop as tasting like cotton wool dipped in vinegar and sugar!

Before leaving Singapore, Margaret started to dislike the heat and concluded that she would never find happiness in tropical countries. However, the interesting sights seen from the Rajah’s 250 tonne wooden gunboat, the Heartsease, soon took her mind off the clammy tropical weather.

As they traced the Sarawak coast, Margaret saw mangrove trees and nipa palms. She described the latter as something that resembled gigantic horse plumes. Then, for the first time in her life, she saw crocodiles after what was presumed as wooden logs on the mud flats started making for the water when the boat approached.

Many questions started surfacing as Margaret ventured deeper into her new realm. Her inability to secure answers from the local members of the crew steeled her resolve to understand the Malay language and befriend the people.

The boat finally reached Kuching after steaming up the Sarawak River for two and a half hours. Its arrival was met by a series of gun salutes, fired to welcome the Rajah back to his home, the Astana. In the distance, Margaret could see that it was composed of three long bungalows, roofed with wooden shingles, and a castellated tower which acted as the entrance.

Among the people waiting on the landing-stage steps were state officials and principal merchants of Kuching. Among them, Margaret saw the only two European ladies living in Sarawak. She was told that it wasn’t the custom for local women to accompany their men on public occasions.

ACQUAINTED WITH A NEW LIFE

A few weeks later, the Rajah left for an expedition to the interior. During his absence, Margaret managed to glean a great deal of information from a local Malay named Talip who served as the Rajah’s butler. Upon learning that nearly all the local chiefs had spouses and children, Margaret decided to invite them to a reception at the Astana.

Despite not knowing any Malay words, Margaret walked confidently into the hall with her copy of William Marsden’s dictionary. Upon arrival, she was escorted by Datu Isa and Datu Siti, the wives of the principal Malay chiefs, to her place of honour. The women addressed Margaret as Rajah Ranee, declaring that she was like a mother to all of them and that they’d always cherish her.

New friendships were forged that evening and Margaret happily declared that her home-sickness had completely vanished. The days that followed saw her receiving an endless stream of female visitors. Their initial halting conversations turned fluent over time.

During one of their meetings, Margaret was delighted when Datu Isa suggested that a local dress be made to befit the Ranee of Sarawak. The garment came with white and gold scarf which was obtained from Mecca. Datu Isa said that women wore the brocade over their heads until only the right eye was visible when they ventured out to public places.

Datu Isa’s daughter-in-law, Dayang Sahada, noticed Margaret’s fascination with the locally-made fabrics and promptly had a large loom sent to the Astana. As she sat down to learn the intricacies of weaving, Margaret suddenly felt that she was no longer bothered about losing some of her European ideas. In fact, she was glad to become more of a mixture between a Dayak and a Malay.

Margaret exhibited her kindness when she rescued a Chinese slave girl who found her way to the Astana to seek refuge from her abusive employer. She remained adamant even when the application to compel the girl to return was issued by the court. The girl was finally allowed to stay at the Astana after Charles learnt the details of the incident.

OF TRAGEDY AND JOY

“Still reading the book? Is it any good?” my friend asks as he places a box of delicious smelling mee rebus on the table in front of me. I nod my head while putting the precious book aside carefully.

During the course of the meal, we discuss an incident where Margaret almost lost her life after contracting an unusual form of malaria. She suffered off and on bouts of fever and discomfort for three months and that reduced her to a mere shadow of herself.

The English doctor who never understood Margaret’s disease prescribed leeches, cupping-glasses and a variety of poultices which made her worse. Concerned over his wife’s health, Charles decided to take her and their three children, born during their four years’ residence in Sarawak, home to England.

The locals adored the Brooke children and were sad to see them leave. Some feared that the long voyage would take a heavy toll on the young ones. And it came true.

The 3-year-old Dayang Ghita Brooke and her year-old twin brothers, James Harry Brooke and Charles Clayton Brooke died within six days of one another and were buried in the Red Sea.

The sudden and unexpected death of all their children devastated Margaret and Charles to no end. Fortunately, the agreeable English weather quickly nursed Margaret back to health and the couple’s seemingly endless political preoccupations kept their minds off sad memories.

The birth of Charles Vyner de Windt Brooke on Sept 26, 1874 in London brought the couple great joy. His arrival was telegraphed to Sarawak where the people rejoiced at the prospect of having an heir to continue the Brooke legacy. It was around this time that Margaret felt that she was strong enough to begin life again amongst her beloved Malays and Dayaks.

Departing for Sarawak in March 1875 and unwilling to tempt fate, the couple decided to leave 6-months-old Charles Vyner in the care of their good friends, Bishop and Mrs MacDougall. The plan was for the baby to stay in England until he celebrated his first birthday.

Aware of his wife’s loneliness in Kuching during his absence, Charles appointed Margaret’s brother, Harry de Windt, as his private secretary. This made her very happy as Harry had a keen interest in travel and exploration. Furthermore, his presence at the Astana would be reassuring for her. While in Sarawak, Harry wrote his first book and became an accomplished author later in life.

A MOTHER TIL THE END

More great news awaited the Brookes when they arrived. Among those in the welcoming party at the Astana were Margaret’s Malay women friends. A beaming Datu Isa proudly presented four additions to her army of grandchildren.

“Enough talk. We better finish packing or we will never complete the task. You may borrow the book and return it when we next meet,” my friend exclaims with finality as he starts to clear away the empty food containers.

Motivated to know the rest of Margaret’s tale, I finish the remainder of the task in double quick time before politely taking leave of my friend. Once home, I make a beeline for my favourite chair before settling down to continue with my reading of the saga.

The Brookes welcomed the arrival of Charles Vyner and his English nurse later that year. Coming in with the afternoon mail steamer, the poor child was badly startled when the cannons at the nearby fort were fired to announce the boat’s arrival.

Things were going very well for the Brooke household. Around Christmas 1875, Margaret realised she was pregnant again. Bertram Willes Dayrell Brooke, the Tuan Muda of Sarawak was born on Aug 8, 1876. Three years later, the family was completed with arrival of the youngest child in the family, Harry Keppel Brooke, the Tuan Bongsu.

As time went on, Margaret found it necessary to spend time away from Sarawak for the sake of her children’s education. One of the happiest periods of her life occurred just before Bertram went to Cambridge. Both mother and son made a trip back to Sarawak to renew ties with their Malay friends.

The last few chapters in the book deals with Margaret’s life in London as she watched her boys grow up and helped to arrange their marriages by organising social events for the British aristocracy and introducing her sons to eligible daughters of British nobility.

Margaret featured prominently in the London social circle and made friends with several of the leading literary talents of the 1890s, such as Oscar Wilde and Henry James. Apart from the book in my hands, Margaret also wrote Impromptus (1923) and Good Morning & Good Night (1934).

Living to a ripe old age of 87, Margaret passed away peacefully in London on Dec 1, 1936. Her loyal friends and the people of Sarawak would always remember her as the Great Queen or Ranee who sincerely loved and cared for them right from the time she made their acquaintance until her dying breath.