In Banggai, located in the Central Sulawesi province of Indonesia, Sheherazade Jayadi is conducting an outreach programme with a twist. The 23-year-old is a Master of Science student at the Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department, University of Florida, and President of Tambora, a network for young conservationists in Indonesia. Sheherazade is researching on the pollination services of flying foxes (fruit bats) and learns that this species is hunted as bush meat, and their colonies are frequently disturbed by villagers.

To address these pressures on their population, she designed a game called ‘Flight of the Flying Fox’. The game aims to create awareness amongst the locals about the role of flying foxes in helping to maintain their forest, and how these animals supply them with economically and culturally important semi-wild durian fruits.

Sheherazade is one of the growing numbers of conservationists in the region who are using the game approach to communicate environmental messages. She’s a former participant of the Wildlife Conservation Course carried out by Dr Cedric Tan from the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), which is part of the Zoology Department at Oxford University.

Sheherazade attended the course in 2015 which transformed the way she engages the public about her research. “Prior to this, I conducted my outreach work via the ‘traditional way’ — going to schools and explaining about saving endemic animals like the Maleo bird with only a poster, and providing scientific descriptions of the animals. It was quite boring,” she shares.

But after joining Tan’s course, she realised that there were creative and fun ways to do conservation education, and was inspired to test this approach at her field site. She discussed the game design for the ‘Flight of the Flying Fox’ with Tan and her counterpart from Conservation Asia, Susan Tsang last year.

Recalls Sheherazade: “The children in the Banggai community were very happy since I used cute prototypes such as durian and bats made of squishy materials and foam. In general, they were keen to participate because it didn’t feel like a standard outreach activity for them. I think we managed to deliver several key messages to the children. For example, there would be less of their favourite durian fruits if there are no bats; no bats means no durian if you allow hunters to keep culling them.”

A new batch of conservationists from Southeast Asia have been exposed to this exciting approach as another Wildlife Conservation Course, which is in its third year, concluded in Malaysia recently.

GAMES FOR EXPERIENTIAL AND ACTIVE LEARNING

Twenty-five participants of the Wildlife Conservation Course listen intently as its director, Dr Cedric Tan explains how to measure the density of animals using a game called ‘Camera Trapping and Analysis’ laid out on a table. The groups would get up to move their pieces made of card when they get the questions right. The participants comprise conservation biologists and community outreach officers from Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Sri Lanka. For these young conservationists, the two-week course held at the University of Nottingham in Selangor, marks their first experience with a novel pedagogical approach aimed at enhancing their practical wildlife conservation work.

Developed by Tan, the 33 year-old Singaporean is a post-doctoral researcher in innovative teaching at the University of Oxford, and also researches on the ecology of clouded leopards in Peninsular Malaysia. “The idea to incorporate elements of traditional learning, experiential teaching and role-play gaming started four years ago when I was teaching undergraduates. I came up with games for revision classes and realised that students responded positively to them. Subsequently, I used games not only for revision, but also for teaching, as experiential games work well for my topics.” He adds that students’ involvement in participatory theatre, role-playing, and even using puppets during lessons, left a better impression on them as they were actively learning.

While the thought of dancing and donning costumes might terrify the average biologist, Tan says that his approach to teaching is a matter of incorporating what he loves: art and science. He combined these two passions by producing educational videos with original choreography, lyrics and music. One of these videos earned him the top prize for the 2013 “Dance Your Ph.D”, which interpreted his thesis on the mating process of the red jungle fowl.

“Like other scientists, I allocate a lot of my time for publishing papers. However, I teach with games and conduct research on teaching with games, and I’ve noticed there is few research carried out on environmental education using this approach. I realised I could inspire people about conservation issues through an integrative approach in the arts and education, especially since there’s a gap in disseminating research to non-scientists.”

PLAYING FOR A NOBLE MISSION

To bridge this gap, Tan has developed several games targeting a diverse range of audiences. Through the course, his games have specific aims: for participants to understand different topics, to understand concepts and processes; to understand the perception or roles of different stakeholders. “I use a game like ‘Camera Trapping and Analysis’ for the first objective, and ‘Conservation Genetics Casino’ which uses casino chips to save animal population from extinction for the second objective. To develop insights into controversial and social issues in conservation, the role-play game, ‘Cash, Commons, and Conservation’ serves the third objective.”

But can urgent environmental issues such as wildlife protection and habitat loss be addressed through fun and games? Tan believes that while these are arguably loaded topics, games can zoom into particular narratives that would bring about awareness, and consequently, behavioural change. He cited Sheherazade’s work in Central Sulawesi, which helps locals to change their perception and to think about the long-term impacts of culling flying foxes in their ecosystem.

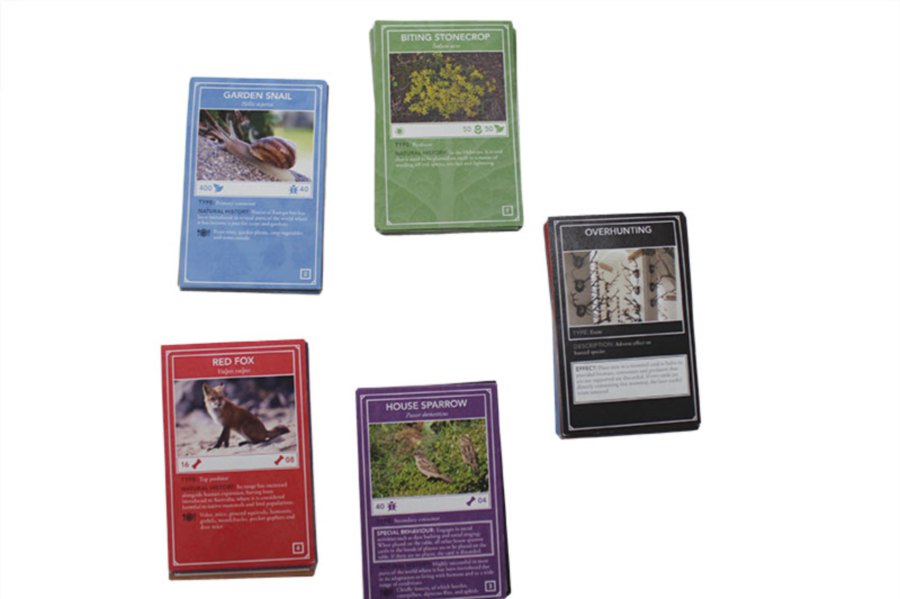

Moreover, although the games he uses in classes and course would need a tutor, there are others which can be played by everyone. “A WWF-Malaysia staff joined my course in 2015, and I’m helping the organisation to develop an educational card game called ‘Eco-Ego’, based on one of the games I designed, ‘Eco-Divo’. This game teaches players about the natural history of organisms in the United Kingdom and the complex web of life. Players learn about how the species interact, and which human activities will benefit or harm the ecosystem. ‘Eco-Ego’ will be similar in its premise, but with local biodiversity.”

The ‘Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil Smallholders Board Game’ is another example of providing learning phases for a specific group of players. Catered to smallholders, the game explains their role in the global palm oil supply chain and the sustainability standards for oil palm production. The hallmark of an environmental education game, says Tan, lies not only in how fun they are. “When producing games for my class, they need to have some key components. Firstly, it should simulate a real-life scenario. It should also allow for players to have self-determination (players enjoy the process), autonomy (offers a lot of choices and ownership), competence (players ask questions and check answers) and most importantly, relatedness, whereby relationships are established between students and tutor and vice versa.”

To increase interaction between the teams, adds Tan, the games would need to have an element of mitigation where other teams can catch up (i.e. using a sudden twist) and encompass an immersive portion such as role-play.

ART OF SCIENCE COMMUNICATION

The Wildlife Conservation Course isn’t only designed to train participants to be better at gathering and writing data, but to also tap into their potential as environmental educators and communicators. For this purpose, the course features a Science Communication module, which Tan mentions isn’t given enough emphasis by researchers.

This view is echoed by Dr Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, associate professor at the University of Nottingham and Principal Investigator of the Management and Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME). Ahimsa has collaborated with Tan since 2014, and says that while scientists have strengths and skill sets such as being evidence-based, and having credibility and creativity, it’s not enough for the scientific community to merely agree amongst themselves.

Instead, scientists need tools to empower them to become effective communicators. “If you want to be a conservationist, science isn’t enough. The conservation field is interdisciplinary by nature and in it are economy, policy, psychology, culture and values enmeshed. A conservationist needs to understand, care and embrace these issues.”

Furthermore, he explains that while MEME’s primary functions are to generate research and to build capacity within government agencies and local wildlife researchers, the organisation is spending more and more of their time carrying out communication work. “We’re trying to get our message out to local communities, policy makers and the public. We acknowledge that communication is a big part of our job and while many individuals do it, not many institutions recognise it. This is something that a scientist should do, but unfortunately, many don’t have the time to expand into this role.”

Naming David Quammen, E.O Wilson and David McDonald as some of the Science Communicators he looks up to, Ahimsa also explains that it’s an exciting time for conservation science and conservation capacity in Southeast Asia. Young scientists from this region, adds Ahimsa, are increasingly joining the conservation movement and making it their career choice — whether in non-governmental organisations, academia, government agencies or private consultancies that do green work.

Along with that, comes a growing pool of local expertise to address the environmental threats in hotspots across the region such as deforestation and loss of biodiversity. “Every conference or workshop that we organise here (Southeast Asia) receives very good response. In fact, I see so many people in their 20s to late 20s and these young scientists have a strong sense of mission, and a hunger to consume knowledge. They want to connect to other scientists and there’s an increasing demand for activities related to their work.”

SCIENCE ENGAGEMENT FOR POSITIVE CHANGE

With Southeast Asia tagged as a fertile ground to cultivate science communication, Nur Fazrina Mohd Ani, a Protected Areas Programme Officer from WWF-Malaysia, contends that presenting science-related topics to non-experts poses a unique challenge. “A lot of the work I do involves research, advocacy and making economic arguments to the public and private sectors on issues like water catchment areas. Science and conservation isn’t boring and we need the right communication tools and platforms to engage with the public.”

The 26-year-old shares that the Wildlife Conservation Course enabled her to utilise various software programmes for her more technical work and unconventional methods to communicate her project. “I want to show to my stakeholders what excites me about the wonders of nature, and why it’s important to protect it. It’s about making science accessible and relatable to people of all backgrounds.”

Meanwhile, for 25-year-old Ada Chornelia from Indonesia, she’s constantly seeking workshops to build her capacity as a scientist. She’s currently carrying out her Ph.D research on the biological/ecological landscape in China. Describing visual aids and presentations as well as social media as persuasive channels for science communication, she wishes to employ more of them in the future.

Says Ada: “This course has been an eye-opening experience for me in terms of how I can communicate my research using different toolkits to reach a broader audience. I’m also keen to step up collaboration with other researchers as we’re all united with the same mission to protect our natural heritage.”

In spite of being perceived as an added weight, Tan is hopeful that science communication will be part and parcel of a scientist’s work. “More organisations and publications are heading towards this direction. For instance, there are journals that request for researchers to submit a video abstract or interviews of their work. After all, science is sexy, sticky and stimulating. And so are science communicators.”