OXFORD University’s Centre for Islamic Studies’ new iconic building was recently inaugurated by its patron, the Prince of Wales, Prince Charles. The illustrious event in the UK was attended by the Yang di-Pertuan Agung, Sultan Muhammad V, himself an alumnus of this world-renowned institution.

According to Datuk Dr Afifi al-Akiti, a Fellow at Oxford University and an Orang Besar 8 of Perak, the building, designed by the foremost contemporary authority in Islamic architecture, Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil, originally from Egypt, has many landmark architectural features.

This includes the Kuwait Library, Oman Hall, Istanbul Court, exquisite Moroccan Suites, unique load-bearing brick dome of Sheikh Zayd Mosque, and the naturally attractive Prince of Wales Garden.

It’s generally acknowledged by visitors and Oxford dons alike, however, that the Malaysia Auditorium is the crown jewel of the building, says Dr Afifi. At the heart of its design is a series of intricate wood carvings that respects Oxford’s tradition in architecture yet infuses Nusantara influences and traditional craftsmanship.

Afifi, who holds the distinction of being Malaysia’s first academician at the renowned university, says that the carving adorning the entrance to the prestigious Malaysia Auditorium is by Tokoh Kraf Negara, Adiguru Norhaiza Noordin, from Kampong Raja, Besut, Terengganu.

AFFINITY

Cutting a dashing figure in Malay busana wear at the launch of his latest publication, Lakar, in Seri Menanti Negeri Sembilan recently, Norhaiza is one who champions all things traditional and is proud of the Malay heritage.

Taking me back to his childhood more than 40 years ago, Norhaiza recalls that he and his friends used to love heading to the river for their daily afternoon swim. Along the way, they would pass by the old palaces in Kampung Raja.

And without fail, he’d pause to get a glimpse of the intricate wood carvings that adorned the doors, windows and archways. Of these, it was the Istana Tengku Long that always caught his attention. He was only about 11 or 12 then and it didn’t cross his mind to think anything more about it.

However, looking back, Norhaiza says that it was probably around that time that he formed an affinity for the beauty of wood carving. “It must have been the wood that chose me, I feel,” he says, adding that from the moment he answered its call, he was hooked for life.

After completing their schooling, most of his friends went on to enjoy gainful employment but for Norhaiza, a sense of restlessness had set in. One day, he stepped into the famous Wan Su Othman’s wood carving workshop, Bengkel Seni Ukiran Wan Su, in Kampung Alor Lintang, Besut.

And from that day onwards, he found himself spending his days watching the artisans at work. He was mesmerised, captivated by the process, from the drawings to the carvings.

But Wan Su was very strict. The young Norhaiza was welcomed to observe but he wasn’t allowed to touch anything for the first six months. Wan Po, Wan Su’s son, began teaching Norhaiza who would memorise the artwork and draw them when he got home. Determined to learn as much as he could, Norhaiza used every opportunity to study with the two masters.

Thereafter, Norhaiza continued his apprenticeship with other masters like Long Latif and Rahman Long, and from each master carver, he learnt about the different styles, wood management, and more importantly, the values of humility and respect.

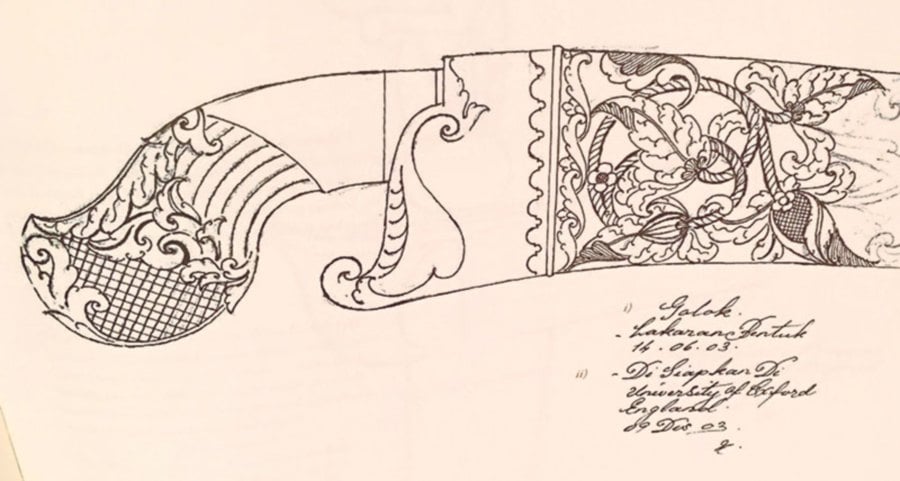

After a few years, he decided to be an apprentice to another master carver, Tengku Ibrahim Tengku Wook. Here he learnt the final basics required to be a good craftsman. It was only in the third year that he was allowed to start work on a carving — his first piece was the hilt of a keris.

LIVING ARCHIVE

After six years with Tengku Ibrahim, Norhaiza sought the old master’s permission to join Nik Rashiddin Nik Hussein as an apprentice. Recalling his years as protege of the late Nik Rashiddin, he shares: “While I previously worked with the old masters to perfect techniques and designs, it was under Nik Rashiddin that I learnt the true meaning and spirit of the wood — the philosophy of carving.

A deeper understanding of traditional wood carving ensured that my work could evolve to embrace the contemporary yet maintain the strong connections to classical designs.”

Together with Nik Rashiddin and his team’s resources at his bengkel (workshop), they created Malay wood carvings that adorned mosques, landmark buildings and institutions nationwide. Nik Rashiddin was a treasure trove — a living archive of drawings and designs on the art of Malay wood carving.

He was the man to go to on the craft and his private collection rivalled any in the country. They travelled widely together, working hand in hand, both devoted to this craft they chose as a lifetime vocation.

When the old master succumbed to cancer in 2002, Norhaiza lost a mentor and friend, and the nation lost its leading expert on wood carving.

But Norhaiza, having worked with Nik Rashiddin for 10 years, inherited the wealth of knowledge passed down from one master to another until that point.

TRADITION

After having spent many years as an understudy with six master carvers, Norhaiza went on to widen his research and study of wood carvings all over the region, a pursuit he inherited from his long years with the late Nik Rashiddin. He has published countless articles in journals and conducted various workshops to share his skills and experience.

His earlier publications include Ukiran Melayu Warisan Melayu (published by Kraftangan Malaysia), The Spirit of Wood, The Art of Malay Woodcarving, commemorating exhibitions at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore, as well as at the Brunei Gallery in the University of London, in 2003 and 2004 respectively, and Jejak Langkasuka.

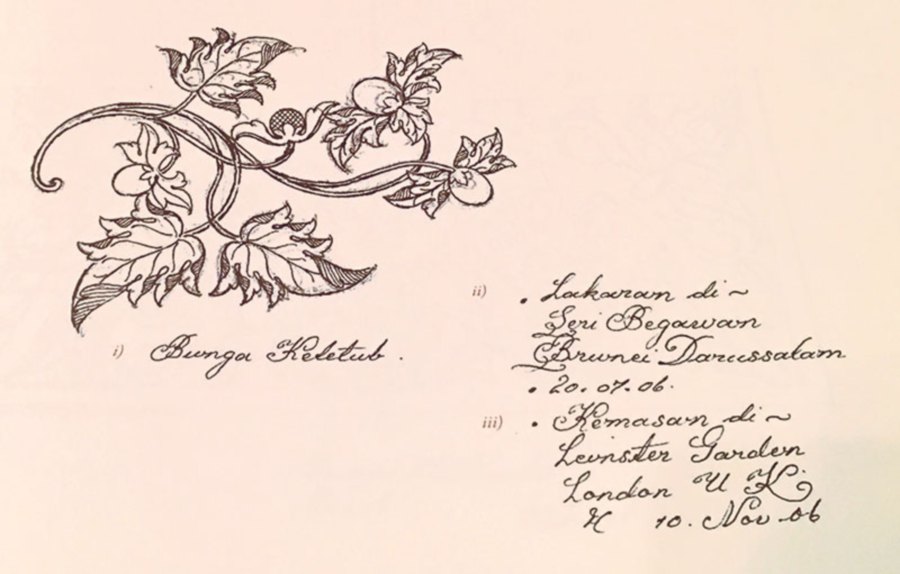

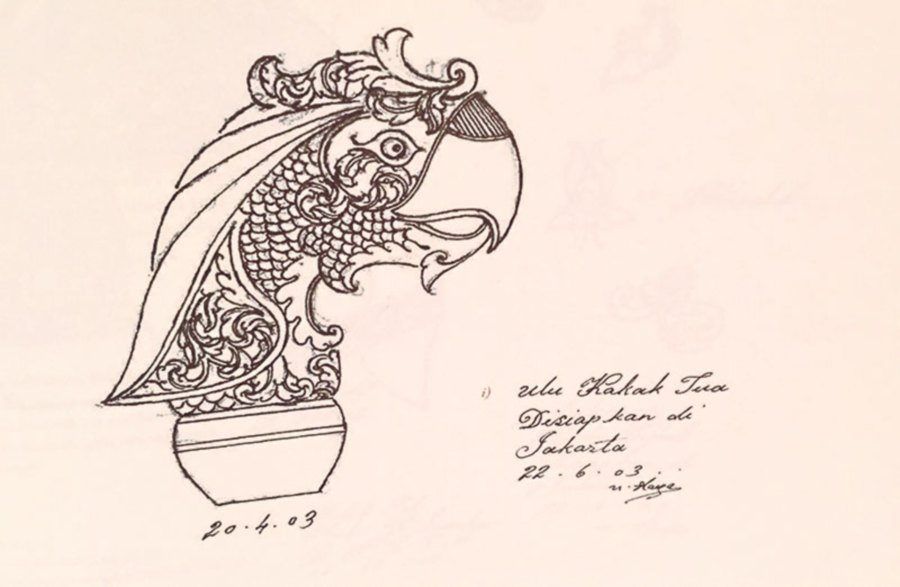

His latest book, Lakar, is a faithful record of his favourite sketchings done over the years at his gallery, Tunjang Bakawali, in Jakarta, Paris, Oxford and many other far-flung places that his passion has taken him to.

Now a master carver in his own right, there’s something else that Norhaiza yearns to do — to share with as many souls as possible his research, work and art.

At his gallery in Kampung Raja, Besut, where it all began, Norhaiza promotes the love not only for wood carving, but for Malay culture and heritage, including pursuits in Malay traditional architecture, ancient manuscripts and antique textiles that reveal the rapidly diminishing old world from the Nusantara.

Perhaps it wasn’t only the spirit of the wood that called out to Norhaiza all those years ago, but the collective memories of our people, seeking out the chosen few to keep alive our countless traditional arts.

ninotaziz believes that our legends and folklores are the memories of our ancient civilisation. She can be contacted at [email protected]