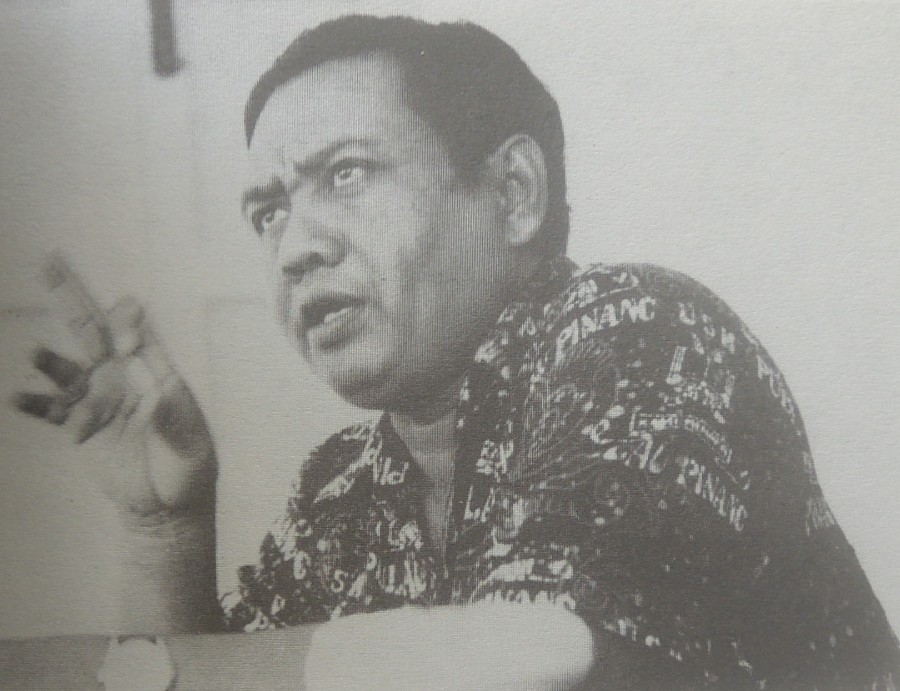

“NATIONAL Laureate Datuk Shahnon Ahmad just passed away.” I look at the text on my phone in disbelief. Shahnon is a giant among Malaysian writers and for a very long time, his writings have had a reverberating effect on local fans as well as readers abroad.

Still trying to get over the news, I head to my study to seek out the section reserved for local writers. Within minutes, no less than 15 literary works by this renowned Kedah-born are piled on my table by the window.

Giving the fruits of Shahnon’s labour a fresh look is my way of mourning his loss. At the same time, I’m curious to find out more about his beginnings and their impact on his subsequent prize-winning work.

Born on Jan 13, 1933, Shahnon was the youngest child of Ahmad Abu Bakar. Ahmad, who hailed from Medan, Sumatra, travelled all over the archipelago as a youth and fell in love with Shahnon’s mother, Kelsum Mohd Saman, in Malaya. The couple settled down in the bride’s home in Kampung Banggol Derdap, a small rural village in Kedah’s Sik district.

Kelsum, just like most of the people in the village, was of Muslim Pattani descent. As a second generation settler, she worked on the padi fields inherited from her father who came to Malaya from the southern Thai village of Kampung Poseng in the late 19th century.

Ahmad, whose fellow villagers referred affectionately to as Pak Mat, first took up work at the Survey Department and later joined the Postal Services as a postman. The outbreak of the Second World War saw Pak Mat taking on a more clandestine role when he was recruited by the British military as their spy.

With detailed knowledge of the local topography since his map preparation days at the Survey Department and thanks to his role as a postman, which enabled him to move about without arousing any suspicion, Pak Mat was the perfect person to keep tabs on Japanese troop movement.

Most importantly, he had free access into military installations at Gurun and Guar Chempedak when delivering mail.

Unable to tell anyone of his activities for fear of his safety as well as those of his loved ones, Pak Mat became one of the many unsung heroes who gallantly played his part in the liberation of Malaya.

As a child going up during the war years, Shahnon was shy, reserved and seldom mixed with others. He spent most of his time with his mother in the fields, catching fighting fish while attending to his designated weeding chores. He also filled his days trapping birds with his self-invented contraptions.

Upon the resumption of life under the British in 1945, Pak Mat began harbouring the thought of sending both his children to an English school in Alor Star, some 72 kilometres away, since they had already completed their primary education before the onset of the Japanese Occupation.

Apart from being frowned upon by his fellow villagers, this unprecedented idea hit a stumbling block when Pak Mat realised that he didn’t have enough to fund his children’s out of district education. The village folk disagreed with Pak Mat as they feared that their children would be converted to Christianity if they attended English schools. So most of them preferred to put their children through the village Islamic education system called sekolah pondok, which they believed to be sufficient to see their children through life.

Fortunately, help came in the form of a monetary reward from the grateful British Intelligence Services. Capitalising on their gratitude, Pak Mat successfully changed his financial windfall into bursaries for his children to study at Sultan Abdul Hamid College. With that, Shahnon and his sibling became the first students from their village to receive an English education.

THE EARLY YEARS

Right from the beginning, Shahnon found hostel life in Alor Star to be worlds apart from that of his village. For the first time in his life, he met peers who came from all walks of life.

They often laughed at his ignorant country bumpkin style of doing things and made jokes about the way he spoke Malay with a strong Pattani slang. Instead of blowing his top, Shahnon took all these in his stride and eventually won his critics over.

Delving deeper into my stack of books, I learn that young Shahnon was largely disinterested in his lessons. The boy felt as though he had been coerced by his father into coming to Alor Star to further his studies. The awkward feeling of living in a large town could be the other contributing factor for his academic ineptness.

Things finally came to a head when the school authorities threatened to withdraw his bursary in light of his lack of progress. I guess the warnings must have injected a sense of reality into Shahnon as he managed to clear his Senior Cambridge with a Grade Three pass.

During the final years of his school life in Alor Star, Shahnon became interested in literature after being introduced to it by his teacher. The teacher gave him several copies of the popular magazine, Mastika. It wasn’t long after when Shahnon became attracted to literary works by established writers like Kamaluddin Muhammad (Keris Mas), Usman Awang (Tongkat Warrant), Awam il-Sarkam and Wijaya Malaat.

After completing his studies, Shahnon took up a temporary teaching position at the English Grammar School in Kuala Terengganu. After teaching English language there for a year, he moved to Port Dickson and enlisted in the Royal Malay Regiment. His attempt to join the armed forces ended prematurely when he suffered an accident two years later and was forced to return to Kedah.

In 1956, Shahnon chose to live in Alor Star and began resurrecting his teaching career. Over the next four years, he taught English in Sekolah Melayu Gunung before moving to Sekolah Melayu Bukit Besar.

Although Shahnon began publishing his work in the 1950s, his short stories at that time went largely unnoticed by the masses. Disenchanted but unwilling to give up completely, he decided put his passion for writing in the back burner while he pursued his teaching career.

Things came full circle in 1960 when Shahnon returned to his alma mater as a Malay language and literature teacher. He remained at Sultan Abdul Hamid College until 1963 when there was an urgent need for the same position in Jitra’s Sekolah Menengah Sultan Abdul Halim.

PEN TO PAPER

With his career already on an even keel, Shahnon began putting pen to paper again. In 1965, he put together a compilation of his earlier short stories, calling it Debu Merah (Red Dust).

Experts believe that he chose the title as it reminded him of the laterite footpaths that criss-crossed his childhood village.

That same year, he made his debut as a novelist with Rentong (The Fallen). This melodramatic work was a breath of fresh air for the Malay literature scene then given the antagonist’s death at the end of the story. Using his village as the backdrop, Shahnon successfully demonstrated the different types of attitudes and realities in his narrative as well as main characters.

His next novel, written in 1966 and titled Ranjau Sepanjang Jalan (Constant Challenges), turned out to be a mega hit. Shahnon’s dedication to his paternal relatives still living in Medan was portrayed in this story which revolved around a peasant family fighting not for life, but for death with nature in their struggle for existence.

INSPIRATION FOR THE SILVER SCREEN

The next milestone in Shahnon’s life was during his first overseas trip to Canberra some time in the middle of 1968.

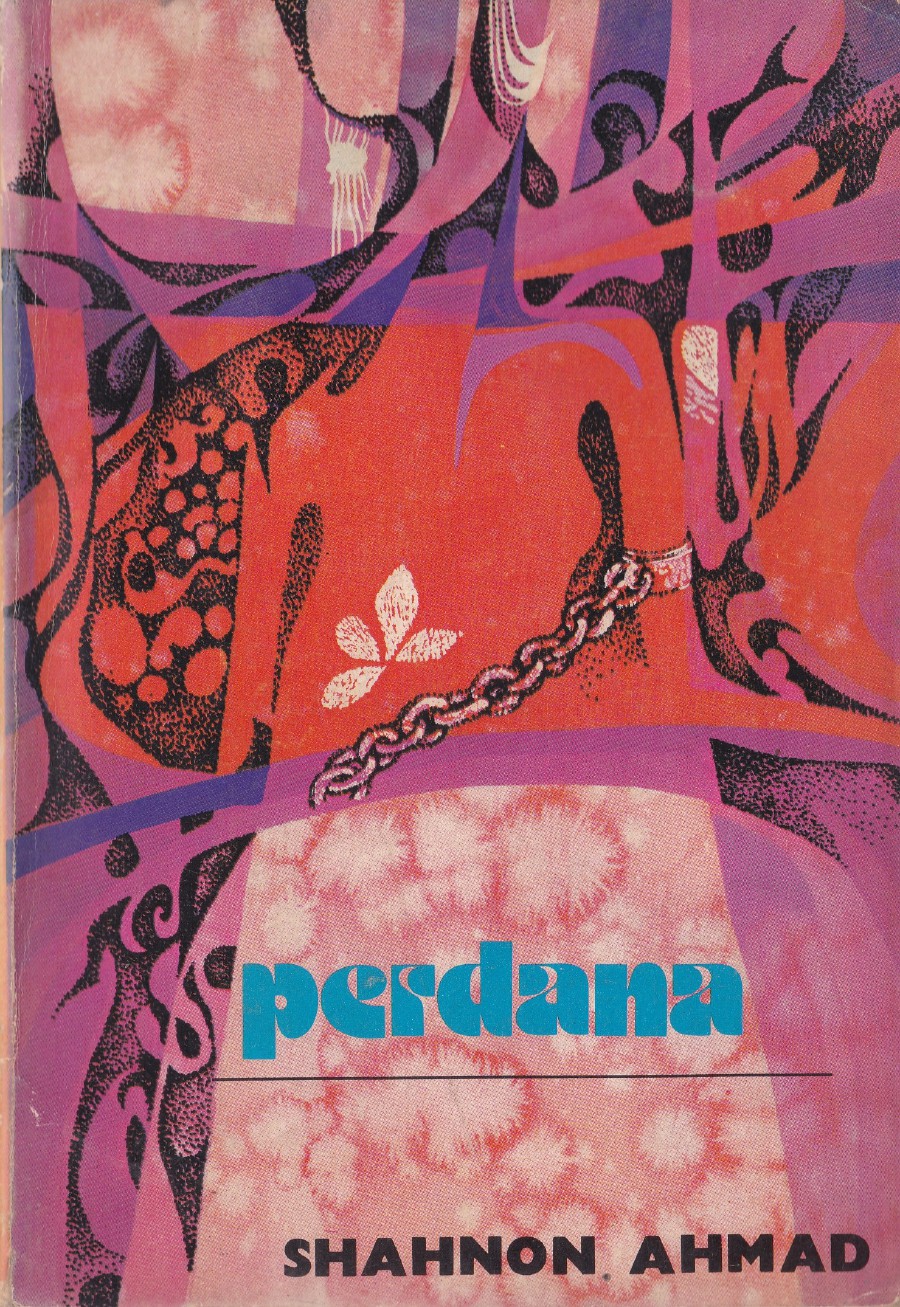

Involving himself in the English-Malay Dictionary project as a research assistant at the Department of Indonesian Languages and Literature, he continued writing during his spare time and came up with Perdana (Prime) in 1969.

While still in Australia, Shahnon even found time to study on a part-time basis under the tutelage of Professor A. H. Johns. Specialising in Malay Studies, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Malay Studies from the Australian National University.

Upon his return to Malaysia in 1972, Shahnon became a lecturer at the Sultan Idris Teachers’ College in Tanjung Malim, Perak. Later that same year, he became a tutor at Universiti Sains Malaysia’s Centre for Humanities while working on his postgraduate thesis titled Poems of A. S. Amin. In 1975, he graduated with a Masters of Arts degree.

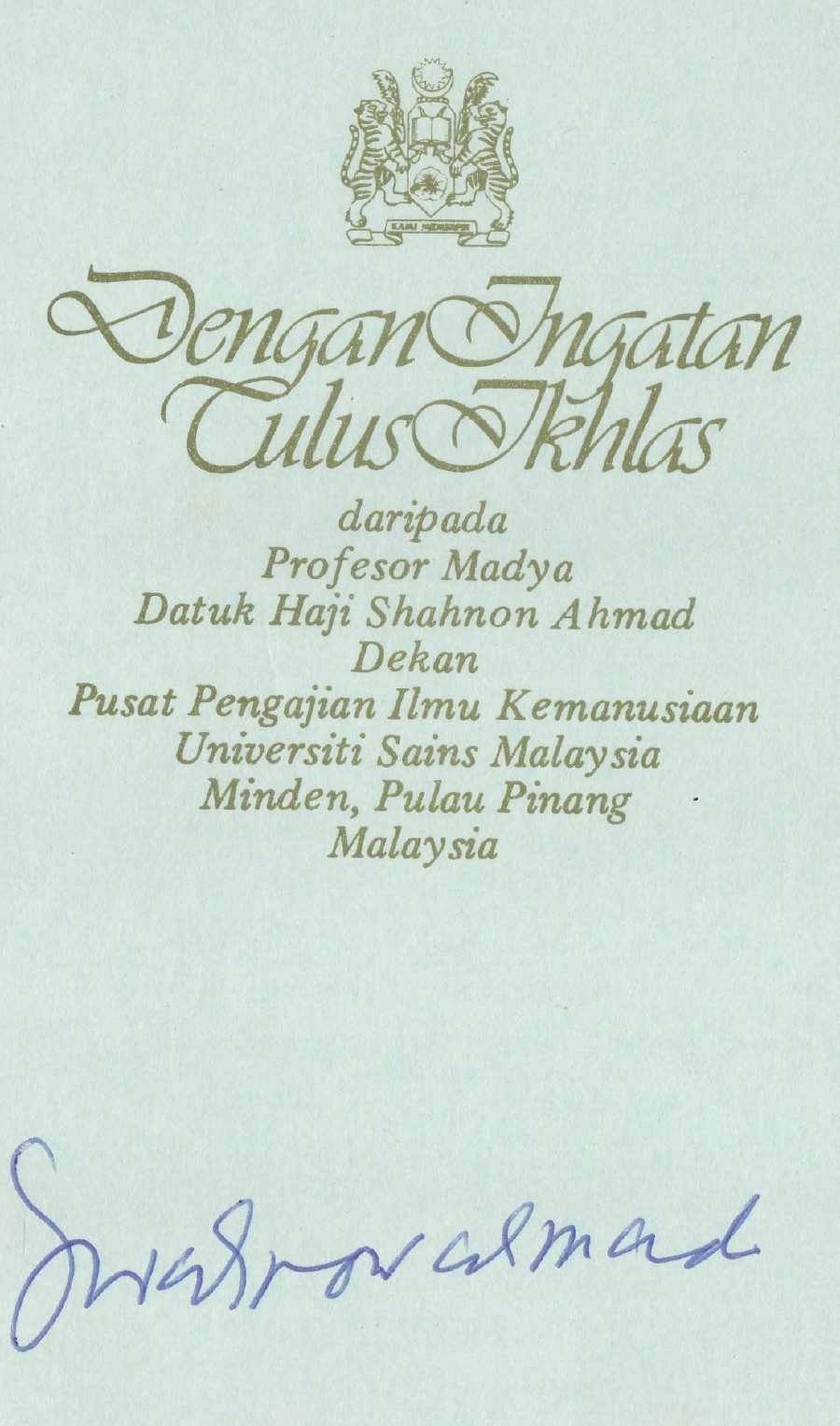

From that time to his recent untimely demise, Shahnon has enjoyed a close connection with Universiti Sains Malaysia. He held the Professor of Literature post there starting from 1982. It was also during that same year that he won the coveted National Literary Award.

Apart from winning countless awards, his work has also been a source of inspiration for the silver screen. In 1983, Ranjau Sepanjang Jalan was adapted into a colour feature film of the same name directed by Jamil Sulong.

Screened in cinemas throughout the country, the highly acclaimed film boasted of famous stars like Sarimah Ahmad and Ahmad Mahmood.

In addition to winning four awards at the 4th Malaysian Film Festival in 1983, Ranjau Sepanjang Jalan became an inspiration for a Cambodian-French film producing company to come up with a motion picture entitled Neak Srey (Rice People) in 1994. The film was set during the time when Cambodia was recovering from atrocities inflicted by the Khmer Rouge regime.

Returning my books back to their places, I find myself wondering whether our nation will ever have another literary giant equal to Shahnon.

Although he has left us, I’m sure that Shahnon’s name will continue to live for generations to come, especially for those who hold his writings close to their hearts.