MEDAN, Indonesia: Ais likes to dance. She knows the words to “I’m a Little Teapot.” Her dimples are disarming.

Her parents didn’t want their daughter to dance. They didn’t want her to sing. They wanted her to die with them for their cause.

Last year, when she was 7, Ais squeezed onto a motorcycle with her mother and brother. They carried a packet that Ais refers to as coconut rice wrapped in banana leaves. Her father and other brother climbed onto a different bike with another parcel. They sped toward a police station in the Indonesian city of Surabaya, a place of mixed faith.

The parcels were bombs, and they were set off at the gate to the police station. Catapulted off the motorcycle by the force of the explosion, Ais rose from the pavement like a ghost, her pale head-to-toe garment fluttering in the chaos. Every other member of her family died. No bystanders were killed. The Islamic State militant group, halfway across the world, claimed responsibility for the attack.

Ais, who is being identified by her nickname (pronounced ah-iss) to protect her privacy, is now part of a deradicalisation programme for children run by the Indonesian Ministry of Social Affairs. In a leafy compound in the capital, Jakarta, she bops to Taylor Swift, reads the Quran and plays games of trust.

Her schoolmates include children of other suicide bombers, and of people who were intent on joining the Islamic State in Syria.

Efforts by Indonesia, home to the world’s largest Muslim population, to purge its society of religiously inspired extremism are being watched keenly by the international counterterrorism community. While the vast majority of Indonesians embrace a moderate form of Islam, a series of suicide attacks has struck the nation, including, in 2016, the first in the region claimed by the Islamic State, also known as ISIS.

Now, with hundreds of Islamic State families trying to escape detention camps in Syria amid Turkish incursions into Kurdish-held territory, the effort has taken on more urgency. The fear is that the Islamic State’s violent ideology will not only renew itself in the Middle East, but may also metastasize thousands of miles away in Indonesia.

There are signs that it is already happening.

Last week, a man whom the police linked to ISIS wounded the Indonesian security minister, Wiranto, in a stabbing. Since then, at least 36 suspected militants who were plotting bombings and other attacks have been arrested in a counterterrorism crackdown, the police said this week.

Hundreds of Indonesians went to Syria to fight for ISIS. In May, the police arrested seven men who had returned from the country and who, the police say, were part of a plot to use Wi-Fi to detonate explosive devices.

The risks, however, are not limited to those who have come back. Indonesians who never left the region are being influenced by the Islamic State from afar.

In January, an Indonesian couple who had tried but failed to reach Syria blew themselves up at a Roman Catholic cathedral in the southern Philippines. More than 20 were killed in the attack, which was claimed by the Islamic State.

In Indonesia, there are thousands of vulnerable children who have been indoctrinated by their extremist parents, according to Khairul Ghazali, who served nearly five years in prison for terrorism-related crimes. He said he came to renounce violence in jail and now runs an Islamic school in the city of Medan, on the island of Sumatra, that draws on his own experience as a former extremist to deradicalise militants’ children.

“We teach them that Islam is a peaceful religion and that jihad is about building not destroying,” Khairul said. “I am a model for the children because I understand where they come from. I know what it is like to suffer. Because I was deradicalised, I know it can be done.”

Despite the scale of the country’s problem, only about 100 children have attended formal deradicalisation programmes in Indonesia, Khairul said. His madrassa, the only one in Indonesia to recei

ve significant government support for deradicalisation work, can teach just 25 militant-linked children at a time, and only through middle school.

Government follow-up is minimal. “The children are not tracked and monitored when they leave,” said Alto Labetubun, an Indonesian terrorism analyst.

When Indonesia achieved independence in 1945, religious diversity was enshrined in the constitution. About 87 per cent of Indonesia’s 270 million people are Muslims, 10 per cent are Christian, and there are adherents of many other faiths in the country.

A tiny fraction of the Muslim majority has agitated violently for a caliphate that would arc across Muslim-dominated parts of Southeast Asia. The latest incarnation of such militant groups is Jamaah Ansharut Daulah, considered the Indonesian affiliate of the Islamic State.

The parents of Ais, who is now 8, were members of a Jamaah Ansharut Daulah cell. Each week, they would pray with other families who had rejected Surabaya’s spiritual diversity.

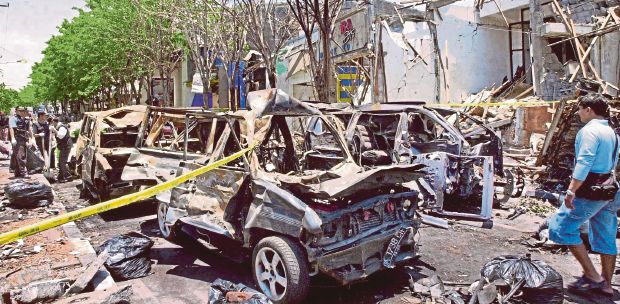

The day before Ais and her family rode up to the police station in May 2018, another family — mother, father, two sons and two daughters — made their way to three churches in Surabaya and detonated their explosives. Fifteen bystanders were killed. The militant family was extinguished entirely, including the two girls, who went to school with Ais.

Hours later, members of two other families in the prayer group also died, either from shootouts with the police or when explosives hidden in their apartment detonated. The six children who survived the carnage are now in the Jakarta programme with Ais.

When they first arrived from Surabaya, the children shrank from music and refrained from drawing images of living things because they believed it conflicted with Islam, social workers said. They were horrified by dancing and by a Christian social worker who didn’t wear a head scarf.

In Surabaya, the children had been forced to watch hours of militant videos every day. One of the boys, now 11, knew how to make a bomb.

“Jihad, martyrdom, war, suicide, those were their goals,” said Sri Wahyuni, one of the social workers taking care of the Surabaya children.

Some day soon, these children of suicide bombers will have to leave the government programme in which they have been enrolled for 15 months. It’s not clear where they will go, although the ministry is searching for a suitable Islamic boarding school for them.

The children of those who tried to reach Syria to fight get even less time at the deradicalisation centre — only a month or two. Some then end up in the juvenile detention system, where they re-encounter extremist ideology, counterterrorism experts said.

“We spend all this time working with them, but if they go back to where they came from, radicalism can enter their hearts very quickly,” said Sri Musfiah, a senior social worker. “It makes me worried.”

Alto, the terrorism analyst, said that even the nascent efforts underway in Indonesia might only be camouflaging the problem.

“Although it seems that they are obedient, it’s a survival mechanism,” he said of the students undergoing deradicalisation. “If you were taken prisoner, you will do and follow what the captor told you to do so that you will get food, water, cigarettes, phone calls.”

But, he added, “you know that one day you will come out.” - New York Times