Malaysia is suddenly caught in an international Catch-22. Should we accept the fortuitous offer to host the 2026 Commonwealth Games and potentially reap its global benefits? Or should we decline, understanding the socio-financial pitfalls it may entail?

The proposition arrived after Victoria, Australia, backed out, citing astronomical costs. Naturally, sports mandarins are enthusiastic, claiming "no big risk", especially after the Commonwealth Games Federation sweetened the offer with an enticing £100 million in financial and strategic support. Moreover, proponents think it's a "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunity to return Malaysia to the world sporting map.

The objectors, including a former sports mandarin, pointedly said hosting the games would be "reckless" because at least four years is required to upgrade venues, plan sponsorships and set up infrastructure.

Besides, the Commonwealth Games isn't a marquee event, insignificant to the Olympics or Asian Games in participation, exposure and returns, so monetisation and spillover benefits are minimal.

An active sports administrator disapproved. "Shocking, financially risky and short-sighted" was his brutal assessment. Nevertheless, a perfunctory SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity and threat) analysis is revealing.

The strength: Hosting the games would give Malaysia an opportune global stage, galvanising the nation to work together, a vital element sorely missing lately.

Thousands of volunteers, college students particularly, would be exposed to and engaged in an invaluable life experience.

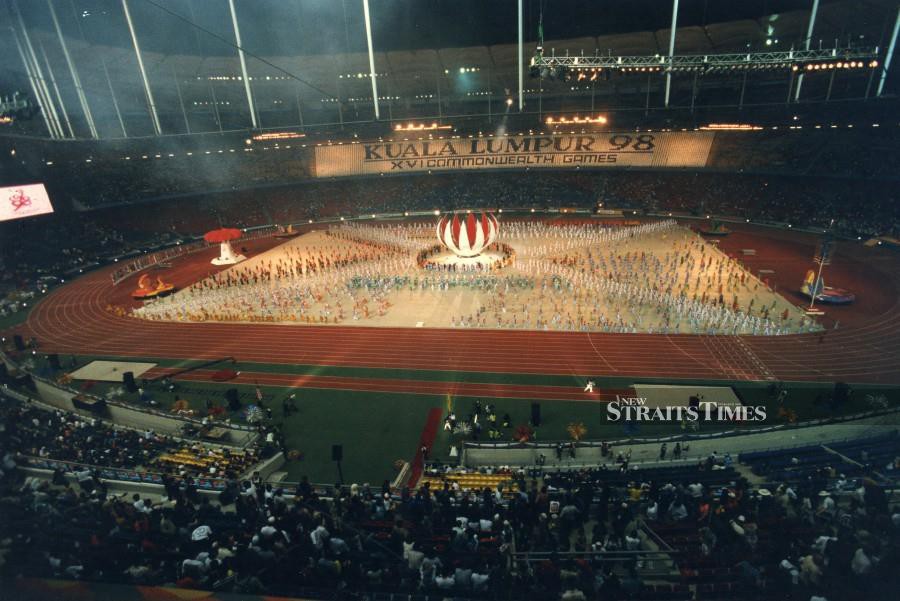

Weaknesses abound though: Malaysia's "well equipped" sports infrastructure is at least 25 years old and may buckle under the immense weight of 5,000 athletes, their contingents and millions of visitors.

Topping it is the need for a new games village. The Bukit Jalil apartments accommodating the 1998 participants were offloaded and other required facilities were phased out, so new, costly structures may have to be built.

The opportunities are obvious: the economic spillover will be a financial bonanza for the hospitality, services and infrastructure sectors still recovering from Covid–19. Indispensable are accommodation, food and beverage, transportation, all-round tourism and the like.

However, the threats, a potential wrench thrown into our socio-political quagmire, might floor hosting prospects. Back then, the federal leadership was focused on elevating Malaysia, pushing mega projects masquerading as dizzying soap boxes.

That 1998 era was immersed in free-wheeling extravagance and waste, fuelled by political schadenfreude, corporate greed and institutionalised corruption. There is also the fact that accounting of spent monies by Sukom 98, now liquidated, is nowhere to be seen.

Now, with a sobering RM1.4 trillion in national debt, hosting costs will be problematic, even with the £100 million offer. But if there's a valid reason to host the games, it is to revitalise our demoralised confidence and rekindle our worldly Malaysia Boleh mojo.