IF long-time Kuala Lumpur inhabitants thought they were experiencing a "sinking feeling" they probably aren't wrong.

They are in good company: Venice, Rotterdam, New York, even a few of our neighbouring megacities, have been sinking for the past 25 years.

Environmental experts think these megacities have until 2030 to work out a fix, even an interim one, or it will be too late to contain the rampaging seas.

Then the only trick left is to turn these megacities into another Netherlands, famous for its river dikes and complex drainage system that has held back the sea and made productive use of the land.

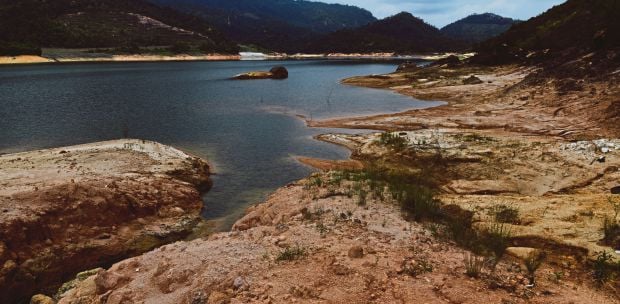

Of all the climate crises afflicting the planet, perhaps the most devastating is how the seas are briskly eroding the coastline. Take a look at Kelantan: in an irony of ironies, the state's desperate drilling for underground water to resolve water supply woes is sinking the easternmost state faster.

Kelantan has been sinking at a rate of 4.2mm a year, thanks to a correlation between subsidence — sinking of land or buildings — and groundwater extraction. The Kelantan problem started decades ago: because of the poor water supply, people dug wells for clean water, not realising that the digging aggravated soil subsidence statewide.

The problem was exacerbated by the biggest sedimentation and erosion in Pantai Mek Mas, and Pantai Kundur and Pantai Cahaya Bulan in Kota Baru respectively. But thanks to a RM20 million project of "beach nourishment" and "rock revetment" system covering 3km, a man-made solution tempered the advancing seas — for now. Like Kelantan, Kedah faces the same vulnerability.

Floods, if uncontained, threaten hectares of maturing padi fields. Penang, too, is vulnerable: plenty of coastline have been transformed from beautiful sandy beaches to rock-filled masonry to check sea erosion, on top of the perennial flooding afflicting Batu Maung, Bayan Lepas and George Town.

Klang is not far behind: since 1995, the royal town and surrounding satellite towns have been extremely vulnerable to rising sea levels that cause flooding.

For all these vulnerable places, drainage and irrigation will be a regular catchphrase in the coming years. Is there a permanent fix? Offhand, plenty of ideas abound.

Like reforesting low-lying, flood-prone areas to regulate water flow and act as storm barriers against erosion and mudslides. This one's tricky: how to stop recalcitrant Malaysians from clogging drains and rivers?

The authorities may have to place surveillance cameras to catch the culprits in the act. There is also the widening and deepening of rivers and drains, besides constructing swales at flood-prone highways, roads and housing areas.

In the meantime, flood-prone areas should have early warning systems and its residents should learn to pack belongings in waterproof containers and store electrical appliances beyond the reach of floodwaters. It's all simple and doable, until the next floods strike.