"WANTED" has a whole new meaning in our post-lockdown world. Labour-starved nations, especially the rich ones, are dangling permanent residency and instant visas to workers who fall anywhere along the muscle-mind spectrum. Or to put it in the language of The New York Times, the physical labour-physics gap. According to the European Union's Schengenvisainfo news website, Germany alone needs 400,000 skilled workers annually to fill the gap caused by the post-lockdown economy.

According to a German study quoted by The Times, Germany will lose five million workers in the next 15 years — a full 3.2 million by 2030. Little wonder, the labour-hungry country saw fit to introduce the German Skilled Immigration Act in March last year to allow migrant workers as long as six months to hunt for a job there.

Up to June this year, 50,000 skilled workers from third countries have been processed through the act, a dismal achievement given the country's annual target of 400,000. And that, too, mostly from a shallow European manpower pool.

But labour shortage isn't just a German mismanagement story. Canada, too, is feeling the muscle-mind pang. If the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation is right, Canada has a Germany-like plan to attract 400,000 migrant workers annually.

Australia is doing the same beginning next month with 200,000 migrant workers as it reopens its economy. The labour pain of advanced economies gives the appearance of being a post-lockdown syndrome. The reason may lie elsewhere.

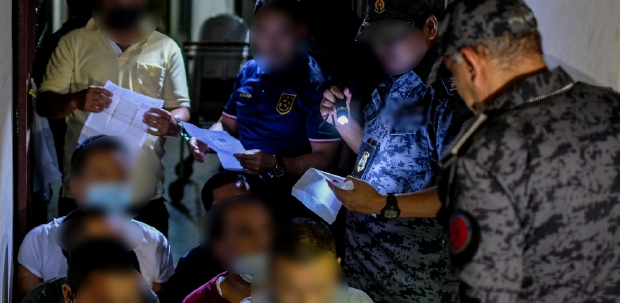

There are two ways out of this quandary, though. The first and the speedier one is to allow asylum seekers and other refugees housed in migrant camps to help fill the shortage. Germany and the rest of the European Union are wasting away human resources at their doorstep.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there were 12 million of them living in Europe as at the end of last year. Of this, a third live in Turkey, the largest refugee-hosting country in the world. If the net is needed to be thrown more globally, there are 82.4 million of what the UNHCR calls "people of concern". Surely, Germany and other advanced economies that are desperate for skilled workers can find in this labour pool what they are looking for. They may want to start with the refugees who are already in Europe.

The second way is to focus more on diversity and less on the politics of integration. Besides, the national labour pool isn't an infinite one as Britain learned the hard way recently. Signing bonuses for truck drivers? Only in short-sighted, Brexit-hit Britain.

Germany and other labour-hungry countries must learn from this insular error. Insularity may make great sense in narrow-minded politics, but never in economics. Given Germany's population is an ageing one, it has no choice but to rely on migrant workers. And this is true of other advanced economies in a similar position.

But migrant workers are mostly non-whites. Politics of integration, especially the Western variety promoted by far-right parties, pays more attention to the colour of the skin rather than on the muscle or the mind that they so badly need. Approached this way, the West's labour shortage will be a pang forever. Dismal though their science is, economists know that wisdom isn't skin-deep. The politicians, too, will come to know this. Eventually. But the world doesn't have the luxury of time.