ON Aug 29, UCSI University established a new Centre of Excellence — the International Institute of Science Diplomacy and Sustainability (IISDS).

The vision is to position the university as a leader in science diplomacy and sustainability for the betterment of Malaysia's interests and those of Asean's and the Global South's.

Such institutes are normally found in the Global North, where the awareness and preparedness to connect the scientific community with policymakers and politicians are more pronounced.

The IISDS may be the first fully fledged centre in the Global South. In welcoming the initiative, Professor Kiyoshi Kurosawa, the former science adviser to Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi said "this may be one of the earliest efforts to offer such training to nationals of developing countries".

To be sure, the 40-year-old World Academy of Sciences has been conducting science diplomacy courses for several years now, but it is located in a developed country — in Trieste, Italy.

Another milestone on the road to opening this institute was the founding of the International Network for Government Science Advice in 2014 by Sir Peter Gluckman, former science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand.

The institute was launched by Foreign Minister Datuk Seri Zambry Abdul Kadir, and he endorsed its aspiration to train "young diplomats, government officials, corporate figures and students on the art and science of science diplomacy".

Science diplomacy is a medium of international relations using science as a tool to build goodwill among nations. Some experts called it "track-two diplomacy", and its importance can never be underestimated.

Here's an example. During the Cold War (1947-1991), geopolitical tension was at its highest between the Soviet Union and the United States and their respective allies. The conflict was based on the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by the two superpowers.

There was no actual large-scale fighting, but the conflict was manifested in a nuclear arms race, psychological warfare, propaganda campaigns, espionage and embargoes.

What was intriguing was the uninterrupted scientific collaboration and dialogue among scientists from these two countries during that uneasy period.

Some experts said the ending of the Cold War was partly aided by this scientific cooperation, at the very least, in averting a full-scale nuclear war — a fine example of the role of science diplomacy.

Today, science diplomacy may be less handy in preventing wars between nations. But it may be key to avoiding a war between humans and nature.

As described by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, humans are conducting a suicidal war against nature, brought about by an unsustainable way of life.

Years ago, in an address in London, the then British prime minister Gordon Brown said: "Many of the challenges we face today are international and — whether it's tackling climate change or fighting disease — these global problems require global solutions… that is why it is important that we create a new role for science in international policymaking and diplomacy… to place science at the heart of the progressive international agenda."

The task is urgent, the problems overwhelming. Just look at the impact of the floods in Pakistan last year, regarded by Guterres as a "climate catastrophe": 1,730 killed, 33 million displaced and over US$40 billion in damage.

Our very own "1-in-100-year" floods in December 2021 left 50 dead, required the evacuation of 400,000 people, and resulted in an estimated RM6.1 billion in losses.

Unprecedented volumes of rainfall left areas on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia under almost four metres of water and turned roads into rivers.

The dynamic interface between science and policy continues. An unfolding "drama of sorts" is taking place right in front of our eyes.

Japan has started releasing treated radioactive water from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the Pacific Ocean, 12 years after a nuclear meltdown.

The government, backed by the UN watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, has declared that the water has negligible radiological impact on people and the environment.

However, not everyone is convinced. There is one radioactive element, tritium, which can't be removed from the contaminated water because there is no technology to do it. Tritium can be found in water all over the world, and many scientists agree that if its level is low, the impact is minimal.

Nevertheless, there are already protests from NGOs in Japan, a ban on Japanese seafood by China, and opposition from South Korea. Before things get worse, it may be prudent for the affected countries to engage in non-emotive dialogue facilitated through a platform of science diplomacy.

Locally, Alliance for Safe Community chairman Tan Sri Lee Lam Thye wants Malaysians to sign a petition to urge the Japanese government to stop the release of treated water from the nuclear power plant.

Lee points out that "Malaysia's geographical location makes it susceptible to the movement of ocean currents, potentially carrying radioactive substances across the Pacific Ocean".

Science diplomacy is not new, but it has never been more important. Many of the defining sustainability challenges of the 21st century — from climate change and food security to poverty reduction and nuclear disarmament, problems embodied in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals — have scientific dimensions.

Not only are the problems multidisciplinary and multisectoral in character, but their solutions lie within the scope of multilateralism.

No one country will be able to solve these problems on its own. The tools, techniques and tactics of foreign policy need to adapt to a world of increasing scientific and technical complexity.

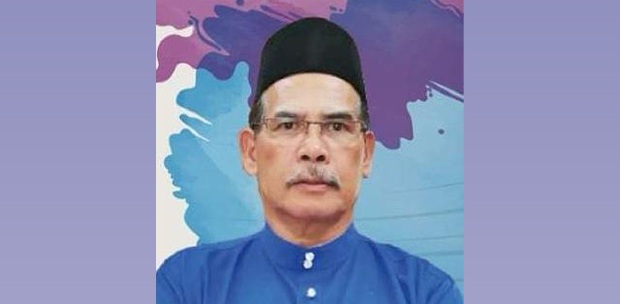

* The writer is the founding director of the IISDS, former science adviser to the prime minister of Malaysia and former member of the then UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon's Scientific Advisory Board