Politics is dynamic — it is constantly changing. Initially, domestic politics is very much influenced by the global phenomenon. What is unthinkable in the past may become a factor that changes the course of a country in the future.

For instance, when political changes swept across Southeast Asia due to the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the governments in neighbouring countries were either forced to change their approach to the people or were overthrown.

Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand went through political upheaval a few decades earlier than Malaysia. The experience made them resilient and capable of managing diversity in democracy.

My point is, inasmuch as we are reluctant to experiment with new ideas and put our faith in obsolete political traditions, we are in danger of becoming stagnant and insular.

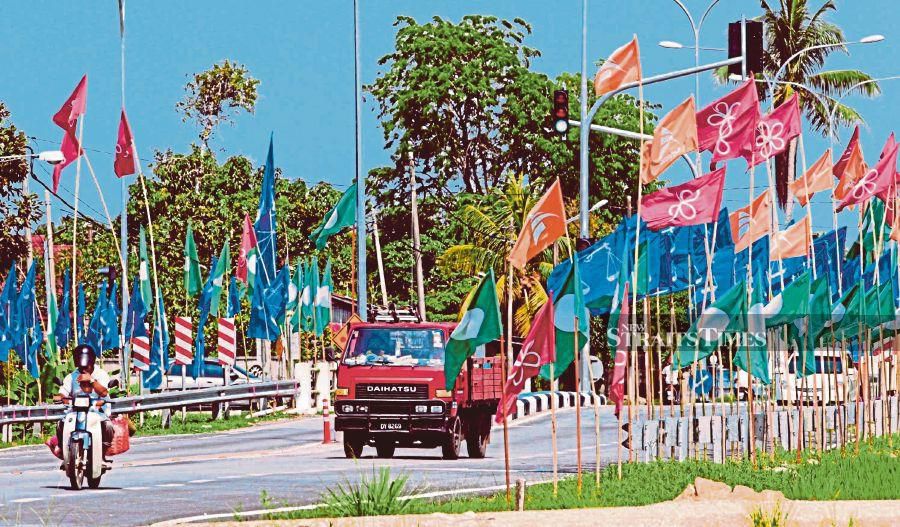

Since the first general election 67 years ago, our thoughts on political coalition have remained unchanged.

Forming a pre-election coalition is a practice that needs to be revised. It is obsolete; post-election negotiations are held hostage by ideological rigidity and political bickering.

Eventually, the warring parties will reignite political strife as soon as the government is formed.

This will interrupt the country's development. The Sheraton Move is the ultimate example of the obsolescence of pre-election negotiation.

I was bewildered to see how a fledgling political party like the Malaysian United Democratic Alliance was dragged into the old- model negotiation while it is advocating for new politics.

With a systematic campaign to persuade six million new voters from age 18 to 30, why beg to be in the vainglorious Pakatan Harapan when it can be a kingmaker?

I understand how our democracy is modelled after the Westminster system. Unfortunately, the system's rigid party whip is hampering the country's progress.

Moreover, this colonial legacy is partially practised in Malaysia. Essentially, the system itself is with numerous grey areas and is easily manipulated.

In 2013, I made a study visit to Germany, courtesy of Friedrich Naumann Stiftung. Throughout the programme, I gained an insight into how German political norms ensure the negotiations on forming a governing coalition are done only after the election is concluded.

In addition, no single party should dominate Parliament. This political norm provides a unique opportunity to form an inclusive and cross-ideological government.

People may disagree by saying the German electoral system is proportional rather than the first-past-the-post system.

Let us not forget, the hung Parliament in the United Kingdom in 2010 forced the Conservative Party to negotiate with the Liberal Democrats.

In the blink of an eye, a British coalition government was formed and governed until the next general election in 2015.

A stable government does not need a two-thirds majority.

A simple majority is sufficient. Unfortunately, we were used to the notion that stability in politics was ensured by the two-thirds majority.

This idea had been embedded in our minds since the first election in 1955.

However, since the 12th General Election in 2008, the ruling party no longer controls a two-thirds majority in Parliament.

This means any attempt at constitutional amendment and passing bills will require cross-party consent.

We already proved that cross-party cooperation could be done in bills like the anti-hopping law and lowering the voting age from 21 to 18.

The way I see it, we need to revise certain practices in our democracy. They must be inclusive and participatory.

At the end of the day, politics itself is dynamic and requires certain revisions to ensure that democracy is still a relevant system.

The writer is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Ethnic Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia