Two events within the span of just three days have suddenly refuelled a heated debate about the possibilities of the amendments in the pacifist constitution of Japan.

On July 8, former premier Shinzo Abe was assassinated, and on July 10, in the parliamentary elections for the upper house, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida's Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior partner, Komeito, won 70 out of 125 seats up for grabs — raising their combined share in the 248-seat chamber to 146 — far beyond the simple majority.

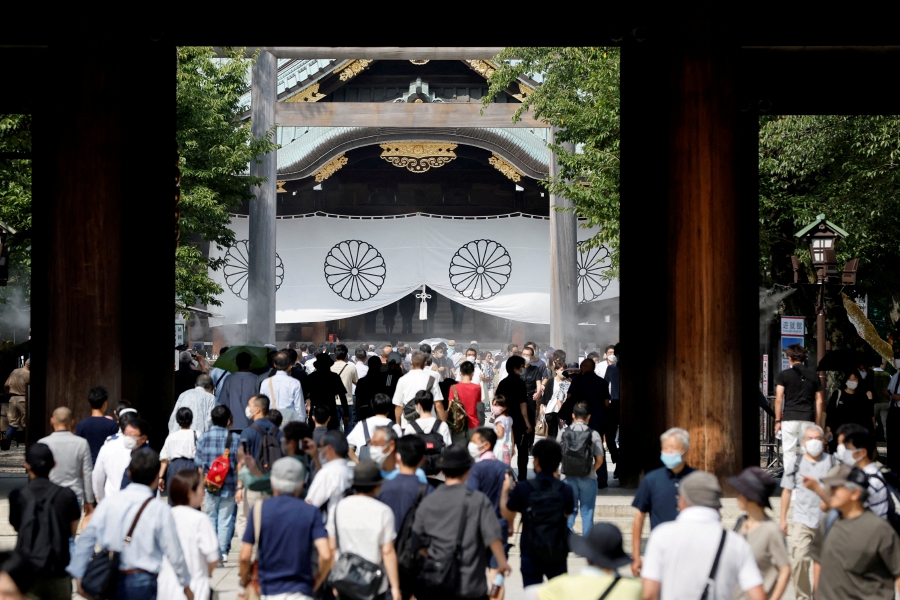

Both events have given new impetus to the decade-old campaign initiated by Abe to transform the structure of the pacifist constitution of Japan that has been in place since 1947.

After World War 2, the pacifist constitution of Japan was promulgated that renounces Japan's ability to wage war and forbids it from maintaining "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential".

This pacifism was further reinforced by the Yoshida doctrine, initiated by the first post-war Japanese premier Shigeru Yoshida, which strongly influenced subsequent generations of the Japanese political leadership to focus on economic development, refrain from militarising and adhere to the pacifist constitution.

Abe was the first Japanese prime minister who openly talked about amending the pacifist constitution.

He took a bold step in 2016 by implementing a new security law to lift the ban on the "right of collective self-defence" and break the restrictions on sending troops overseas that had been in place since 1945 — ostensibly bypassing the core theme of the country's pacifist constitution.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine was a major event that actually jolted the entire spectrum of Japanese society in general.

For obvious reasons, the Ukraine invasion provided the much-needed pretext to the right-wing politicians and Abe to rekindle the topic of amendments in the constitution to make it "at par" with the changing ground realities.

For a very long time, Abe had been talking about the "China threat" as the key element in realigning Japanese foreign policy.

To counter China's expansionism in the East and South China Seas, as well as the Indo-Pacific — his favourite term for the long strategic stretch from East China to the Indian Ocean — Abe pushed hard to involve Japan in numerous regional and sub-regional security "projects" and dialogues, and also campaigning at home for changes to the pacifist constitution.

But, factually speaking, despite all his intense efforts, Abe was never hopeful of achieving this main plank of his doctrine in the near future.

One key factor that has kept the pacifist constitution intact since 1947 without any amendment is the complicated procedure itself.

To do so, more than two-thirds of lawmakers in both the Upper house and the House of Representatives must vote in favour of the proposed amendments, which then need approval from a majority of voters in a national referendum.

The fact is that the perpetually divided Japanese Diet (Parliament) never allowed any government to think about any kind of change in the constitution because of this very reason.

But, for the very first time since 1947, after the results of July 10 elections, the pro-constitutional amendment camp, comprising the LDP-Komeito coalition, two opposition parties and independents, suddenly finds itself well within the range to make it a reality after crossing the 166-seat threshold in the upper chamber needed to push for a first-ever revision of the 1947 Constitution.

This bloc already has secured support in the other chamber.

Perhaps this numerical possibility has encouraged the right-wingers in Japan to rekindle this topic with much more intensity – particularly against the backdrop of a very high wave of public sympathy after the unfortunate assassination of Abe.

There is no doubt that the "remilitarisation" ambitions of the Japanese right-wing forces have been rekindled following the LDP's electoral success.

The principles of the evolution of the global power equation also suggest that Japan will eventually be remilitarised, but the momentum and extent of this process depend upon five major factors.

The first is related to the political outlook of Kishida himself. Unlike Abe and the current secretary-general of the LDP, Toshimitsu Motegi, Kishida is not hawkish in his approach.

It is also true that Kishida, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, seriously rebuked Abe's advocacy for hosting the US nuclear weapons as a deterrent as "unacceptable" while referring to the country's stance of maintaining three principals of non-proliferation.

Kishida's commitment to the Abe doctrine is serious, but he is not expected to be as eager as Abe.

The second issue is that a large portion of the LDP's core team is also sceptical of making any radical changes to the constitution all at once.

The third challenge is from the other side of the political divide that has already started its symbolic protest demonstrations inside the Diet building to preempt such a move from the right-wing camp.

Fourth, public opinion, which is still clearly tilted in favour of keeping the existing constitution intact, and the opposition parties can build an anti-amendment momentum to disrupt the smooth working of the Kishida regime.

The fifth — but external — factor would be Washington's long-term response to this issue.

At the moment, the US is readily supporting the concept of a "re-militarised" Japan with a view to counterbalancing China's growing activism in the region.

By extending Nato membership to a militarised Japan, some hawkish quarters in Nato are eager to create an "Asian Nato" or a "Global Nato" to contain Russia and China from all sides.

But a militarised Japan may prove to be a contrariwise choice for the US in the long run.

Currently, under its exclusively defence-oriented policy, Japan spends one per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Even so, it is the seventh largest military budget in the world. Similarly, the Global Firepower Index (GPI) ranked Japan fifth globally in overall military power.

If the constitution is modified and remilitarisation is allowed, Japan has all the potential to turn into a formidable force with a tendency to break away from the influence of Washington to assert its own stature in the global power structure.

This will certainly be a dreadful scenario for the US. So, the remilitarisation of Japan is fraught with many hazards that can actually shake the global power equation and even create a new "threat" for Washington.

Sooner or later, the remilitarisation of Japan will happen, but its speed and extent will be decided by these factors.

The writer, writing from Pakistan, used to write for some publications in the Asian region