In a world thrust by disintegration and renewal, tradition plays a vital role in perpetuating peaceful coexistence in the region.

Many incidents potentially contribute to the disintegration of Asean. While the military junta in Myanmar is purging pro-democracy activists, the threat of climate change is looming over the region.

What I foresee is the influx of thousands of refugees into our country in the future. The question is how do we aptly react to this situation?

The major school of thought in international relations, either realism, idealism or constructivism, have provided adequate analysis in the context of powers and economic relations.

However, if we dig deeper into our heritage, we might stumble upon the fact that our ancestors have outlined a traditional concept based on local experience.

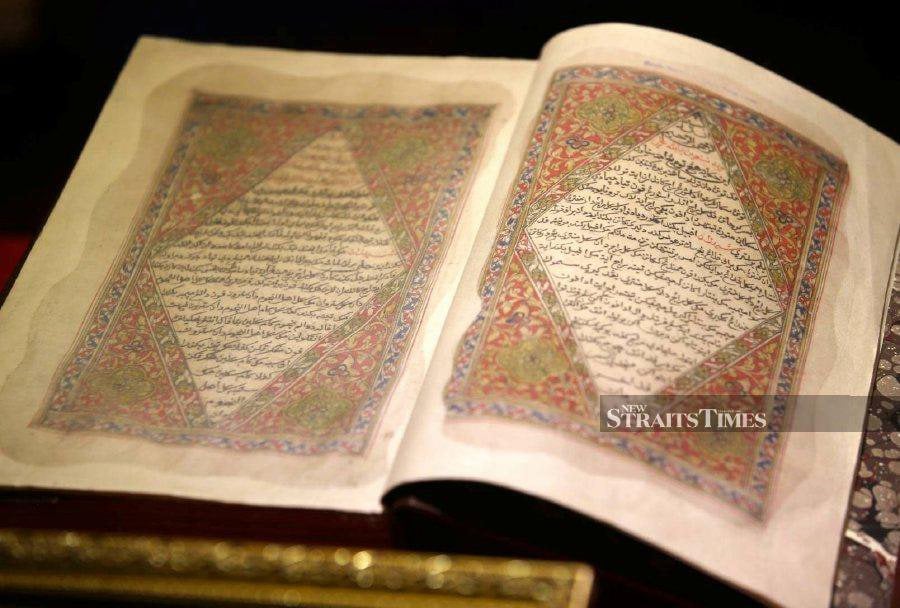

Hikayat Hang Tuah (the Tales of Hang Tuah) is probably the most extensive courtly text on foreign relations.

Interestingly, this tale emphasises compassion and moral balance as values to bridge differences between diverse ethnicities and cultures.

I will start by outlining diplomacy on a people-to-people level.

It was said that Hang Tuah and his friends were on a boat journey when they encountered some pirates on their way to pillage Palembang. After engaging the pirates in hand-to-hand combat, the outnumbered Hang Tuah and his friends sailed off towards Singapore.

It was then by chance that they met the local chieftain of Singapore (Batin Singapura) who ultimately provided a helping hand to repel the enemy.

As I was doing a close reading of the text, I was astonished to find how the Batin Singapura spontaneously declared Hang Tuah and his friends as his relatives.

The chief repeatedly said: "Do not forget me, as we are now relatives" (Jangan lupa akan hamba, kerana kita sudah jadi saudara) to Hang Tuah.

Throughout the second chapter of the Hikayat, the words "bersaudara" (relatives) were repeated at least four times in different situations. This proves how people-to-people relations are not a new thing. Being hospitable to strangers is strongly embedded in our tradition.

I will relate this matter to the current situation concerning Asean solidarity.

"Playing relative" is a traditional concept among the Southeast Asian polities. It is even older than the modern "prosper thy neighbour" adage.

Contrary to the latter, the former advocated "esprit de corps" in helping neighbouring citizens overcome hurdles they might experience.

In the case of the Rohingya who are fleeing from persecution in Myanmar, it contradicts our tradition to drive them away from our shores.

The least that we can do is to relocate them to an island while working closely with international agencies for refugee resettlement.

We had applied the same method while dealing with the influx of Vietnamese refugees in the 70s. Pulau Bidong in Trengganu was set up in 1978 as a temporary refugee camp.

The government managed to facilitate the resettlement process until the last refugee left Malaysia in 2005. Therefore, why are we suddenly suffering from selective amnesia while dealing with similar cases nowadays?

The Malay term "nama" (prestige) is a constitutive concept vital in explaining the state's behaviour in foreign relations.

It was Anthony Milner, a distinguished historian of Southeast Asia, who expounded on the significance behind nama. The Hikayat makes clear the importance of exquisite manners and eloquent language in enhancing one's nama.

Malaysia was the one that actively promoted a transnational regional identity through a "people-centred Asean" in 2015.

By taking an active role in managing the refugees, Malaysia simultaneously enhanced its nama as the champion of international humanitarianism.

Hence, contrary to the western concept of power balance, we are advocating a moral balance by displaying an exquisite manner of nama and playing relative in our foreign relations approach.

At the end of the day, we must realise there are many traditional concepts by our forefathers that have yet to be discovered in the Hikayat to be our guide in foreign relations.

The writer is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Ethnic Studies

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the New Straits Times