Language is the only legitimate weapon in diplomacy. In the diplomatic world, the argument between two contradictory ideas is won over the more coherent and sound argument.

World War 2 broke out owing to the League of Nations' inability in managing disagreement and the war of words. Therefore, it is safe to assume, that the world's peace was perpetuated by the articulation of language.

On March 23, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob proposed to elevate the status of the Malay language as Asean's second working language. The first attempt by Malaysia to suggest a similar proposal was in 2017. Although both times the proposal was met with numerous criticisms, nonetheless, it has a logical point.

Historically, Asean was founded based on an ethnocultural grouping. To date, the Malay language is spoken in four out of 10 member states and is already gazetted as the national language.

As a regional bloc that relatively emerged against the backdrop of the Cold War, Asean was struggling at the beginning to set the working language of the fledgling organisation. To resonate with the rest of the world, English was made the de facto working language of the organisation as codified in Article 34 of the Asean Charter.

Nonetheless, by framing it as the second language, it is intended to supplement a working language of Asean's, but not to the extent of replacing English's status quo in the organisation.

Unfortunately, the proposal by Putrajaya inadvertently reinvigorates long-time cultural squabbles between Malaysia and Indonesia.

Both have a long history of diplomatic spats ranging from cultural heritages and territorial disputes to petty disagreements over gastronomy.

There was a time when the Malaysian government used the folk tune Rasa Sayang to promote its tourism campaign.

Claiming the rights to the song, the Indonesian right wing began to advocate for staging a protest outside the Malaysian embassy in Jakarta.

Cultural heritage is an emotional issue for both countries. The most sensitive one is language.

I was appalled by the argument by Indonesia's Education, Culture, Research, and Technology Minister Nadiem Makarim, who rejected Malaysia's proposal.

Being someone from a business background, his argument was culturally shallow and nonchalant. To understand the point of contention, we must analyse it through the historical account of how a one-time lingua franca was divided into two different languages.

Initially, we must acknowledge that Indonesia and Malaysia were post-colonial states and were founded about seven decades ago. Before the existence of modern geopolitical lines, the Malay language was the lingua franca spoken by the inhabitants of the Malay Archipelago.

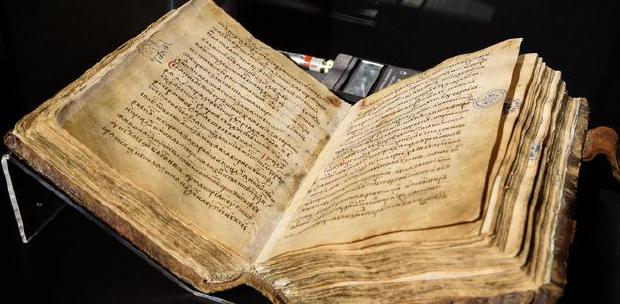

The 16th-century great Sufist poet, Hamzah Fansuri, dictated his famous Syair Perahu in the Malay language. Another par excellence literary scholar, Raja Ali Haji, wrote his famous manuscript Tuhfat Al-Nafis (the Precious Gift) in the Malay language. These two scholars were immensely celebrated in modern-day Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Brunei.

In my opinion, for hundreds of years, our ancestors were speaking and penning down extraordinary ideas in the same language. It might be of different variants of syntax and phonology; however, it is still the same language we have inherited.

The evolution of Bahasa Indonesia and Bahasa Malaysia is merely an invention of the tradition. By formulating various forms of Malay, the invention is solely serving nationalistic purposes.

In retrospect, the famous Oath of the Youth (Soempah Pemoeda) of Oct 28, 1928, galvanised the sense of nationalism through the famous slogan "satu nusa, satu bangsa, satu bahasa" (one country, one nation, and one language). This historical event marked the time when the founding fathers of Indonesia embraced the Malay language as the linguistic foundation of a new nation.

The ethnocultural affinity between Malaysia and Indonesia should bridge the differences between the two modern nation-states. The Indo-Malay solidarity must remain a basis to strengthen "togetherness" in Asean.

Nonetheless, as Asean is shackled with other pressing issues, such as regional economic recession due to the outbreak of Covid-19, Myanmar consistently ignoring the Five-Point Consensus, and geopolitical competition between major powers, the regional working language is the last thing to be included in Asean's agenda.

We should not forget that the idea of Asean was born out of the brotherly relationship of our founding fathers. In the words of the late Tun Ghazali Shafie, unity, and togetherness (of Asean) must never be governed by a sense of exclusiveness.

The writer is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA-UKM)

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the New Straits Times