THE Covid-19 pandemic has intensified the Sino-American geopolitical rivalry. This is the most aggressive rivalry since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s.

Unlike the last time, the United States has yet to offer a practical economic and political model to global south states as part of a strategic move to outmanoeuvre China.

While US President Joe Biden is likely to shift his foreign policy priority to the Indo-Pacific, the legacy of Trump's policy in the Middle East remains a thorny issue that distracts Washington's strategic planning to outwit China's growing assertiveness. Tension is brewing, yet no side dares to fire the first volley.

Cold War narratives between the US and the Soviet Union were built on elaborate military expenditures, proxy wars and the dichotomy between free and totalitarian societies. Nonetheless, the rules of engagement in engaging the new adversary have changed.

Unlike the Soviets, China is backed by a strong economy, advanced technologies and a global investment network of state-owned conglomerates entrusted to run numerous Belt and Roads Initiative projects. China is the embodiment of the new breed of communism with a capitalist mindset.

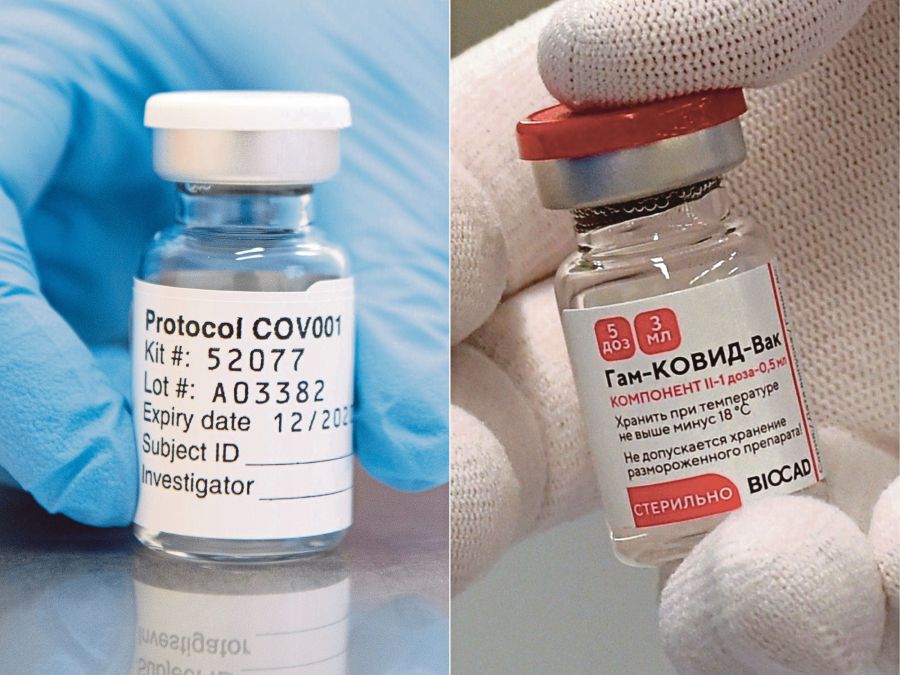

Vaccine production has taken "vaccine nationalism" into the international relations discourse. Vaccine nationalism as a form of realpolitik can boost a nation's geopolitical gain. Regrettably, it is gaining momentum alongside anti-immigrant sentiments and the rise of right-wing politics in many countries.

Presently, Covid-19 vaccines have been developed mainly by medically advanced countries. Problems arise when a producer country is reluctant to share its supply with others until its inoculation programme is completed.

Up to this point, the US and the United Kingdom have not made any commitment to provide their supply even to their long-time allies in the global south.

Through a charm offensive, Chinese-made vaccines, namely Sinopharm and Sinovac, have already reached 69 global south countries in five continents. Meanwhile, the G7 countries are grappling with the intellectual property rights of vaccines.

Vaccine diplomacy is a manifestation of the rivalry between superpowers. Although vaccine production and access are part of the "global public good", diplomatic alignment is still a potent force in determining the procurement of vaccine supply from which manufacturers.

Looking at the pattern of global vaccine distribution, procurement is almost always done according to one's sphere of influence.

For example, former Eastern Bloc countries like Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic have opted for the Russian-made Sputnik V vaccine even though it is not approved by the European Medicines Agency yet.

Gradually, the pharmaceutical industry has replaced the military-industrial complex as the structure behind the superpowers' rivalry.

How should Malaysia appropriately respond to this rivalry? Historically, in the first 10 years post-independence, our foreign policy leaned towards the western bloc.

A watershed in Malaysia's foreign policy came with the ascension of Tun Abdul Razak Hussein, who adopted a policy of non-alignment and navigated Malaysia through the adversarial nature of the international system then.

Malaysia's foreign policy is always a change in continuity. But non-alignment remains a guiding principle in the conduct of our external relations.

As a middle power, Malaysia is cognisant of the way to survive and succeed by hedging and balancing itself with the superpowers. The strength of middle power countries lies in their ability to negotiate and cooperate through multilateral diplomacy.

As stated in the National Covid-19 Immunisation Programme booklet, Malaysia is getting vaccine supplies from several pharmaceutical companies, namely Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sinovac, CanSinoBio and Sputnik V.

Procurement of these vaccines was mainly done through bilateral negotiations between Malaysia and the producer country.

Recently, there was talk between Malaysia and Brunei to engage in reciprocal cooperation for inoculations. As a foreign policy observer, I believe this bilateral cooperation must become multilateral by bringing in other Asean countries. After all, our surroundings play a pivotal part in achieving total immunisation.

The World Health Organisation director-general recently urged G7 countries to waive intellectual property protections for Covid-19 vaccines. If this happens, Malaysia must take this matter to Asean to jointly develop a vaccine that suits Southeast Asia's tropical climate.

Although developing a regional vaccine would be an uphill battle, we must at least try to emulate the success of the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality — neutrality from the global vaccine tug of war.

The writer is executive director of NADI Centre, a consulting firm focused on strategic policy research and advocacy