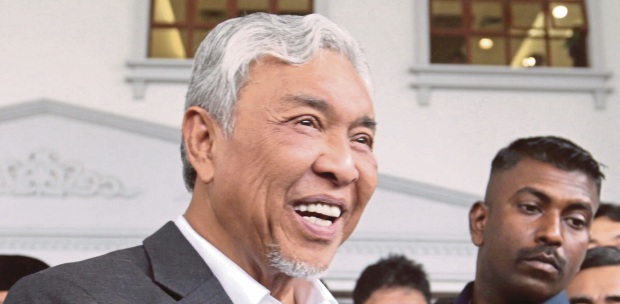

A former student called me last Friday, wanting to know what I thought about Umno president Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi's RM220 million defamation suit against a news portal.

I told him that the Umno president was entitled to do that if he felt his reputation was under attack, but winning the suit was another matter.

We have an adversarial judicial system, where the final outcome is never guaranteed.

A plaintiff may win at the High Court but may still lose at the appellate stage (Court of Appeal or Federal Court).

I then told him that was exactly what happened to a defamation suit filed by a Sabah political leader, Tan Sri Harris Salleh, against an author and several other defendants responsible for publishing and distributing a book titled Vendetta and Abuse of Power.

In his claim, Harris said the defendants had made baseless allegations against him in certain passages of the book.

He claimed that these allegations were maliciously written, and in their natural meaning and by innuendo, these offending passages implied that he was a corrupted person and had abused his power.

At the trial stage (Kota Kinabalu High Court), the judge ruled that the plaintiff had proven his case and that the defendants had failed to prove their defence of justification and fair comment. The plaintiff was awarded a total of RM350,000 in damages and costs.

On appeal by the first and second defendants, the Court of Appeal held that if the trial judge had correctly considered the evidence adduced in court, "he would have found that the pleaded defence of justification would have succeeded".

The Court of Appeal said the trial judge had erred, and his decision (in favour of Harris) was set aside.

I reminded my former student that if the first and second defendants in that Sabah case did not have the money and the stamina to continue the fight to the Court of Appeal, they would have lost in their judicial combat against the Sabah politician.

Victory in a defamation suit (whether you are a plaintiff or a defendant) requires a lot of money (for legal fees and costs), endurance and stamina (faith that you are in the right), and, of course, evidence and witnesses to back up your case.

A defamation suit can sometimes backfire.

In Abdul Rahman Talib v. Seenivasagam (1966) 2 MLJ 66, the plaintiff (a cabinet minister) had sued the defendant (an opposition politician) for alleging that he was involved in corrupt practices.

In his defence, the defendant pleaded qualified privilege, fair comment and justification.

The trial judge held that the defence of qualified privilege failed but the defence of justification succeeded.

When the case went up on appeal, the Federal Court upheld the trial judge's decision.

The plaintiff later resigned from his cabinet post and the first prime minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman, posted him to Egypt as ambassador.

If he had not taken the civil action against the defendant (and later lost it), nothing would have happened to his political career and the public would not even have thought twice about the alleged corrupt practices.

A plaintiff seeking substantial damages from a defendant may discover that even if he wins the case, the court may have other ideas about the subject.

This happened in Grobbelaar v. News Group Newspapers Ltd (2002) 1 WLR 3024. In this case, the defendant newspaper had alleged that the plaintiff was involved in match fixing, and the plaintiff had filed a defamation suit against it.

The plaintiff succeeded in proving his case and the court delivered a verdict in his favour, but awarded him only £1 in damages (known as contemptuous damages).

Contemptuous damages are awarded when the court finds that although the plaintiff is technically entitled to succeed, it believes that the action should not have been brought up (and was wasting the court's time).

Contemptuous damages are awarded where the injury to the plaintiff's reputation is regarded as minimal.

Zahid's defamation action against the news portal will probably take some time to conclude.

By that time, the Kuala Lumpur High Court might have already handed down its verdict in regard to the current criminal proceedings against him.

It will be an extremely interesting defamation case to watch, especially since, as I said earlier, the final outcome is never guaranteed.

The writer, a former federal counsel at the Attorney-General's Chambers, is deputy chairman of the Kuala Lumpur Foundation to Criminalise War

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the New Straits Times