LET me describe two scenarios. In Myanmar, there was a general election on Nov 8 last year.

As in the previous election in 2015, Oxford graduate and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy captured a resounding victory.

The country's influential military did not like the results and on Feb1this year, declared them void and overturned the election.

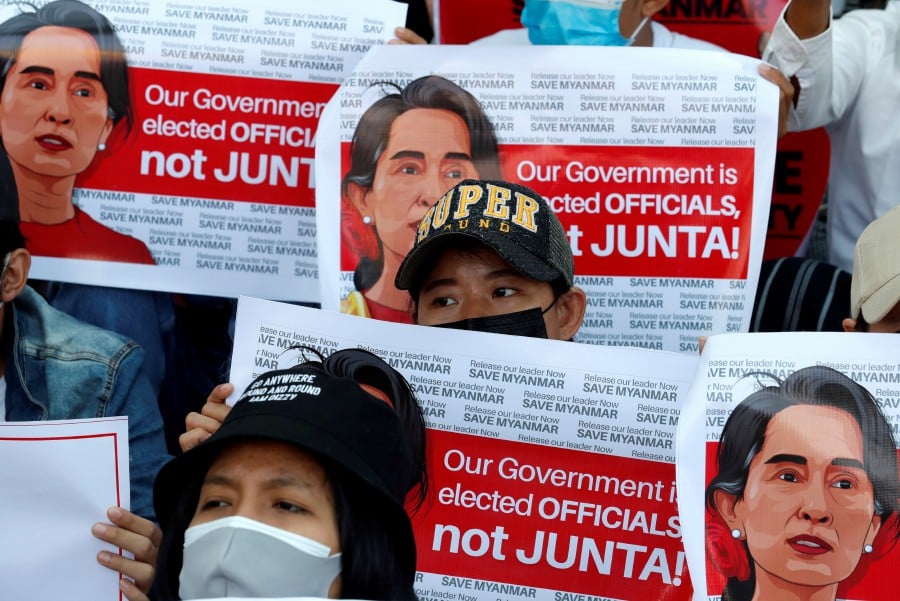

The generals staged a coup, seized power and put Suu Kyi and other prominent leaders of her party under house arrest. Tens of thousands of protesters, including teachers and Buddhist monks, took to the streets to defy military dictatorship and to restore "democracy".

The protests attracted a great mass of people from different walks of life. This time, anti-military demonstrations seem to have received greater encouragement from the people of Myanmar and wider attention internationally.

I will mention two incidents involving the other scenario. On Dec 10, 2016, The Guardian published the story of the Rohingya woman, Noor Ayesha, and her surviving child, Dilnawaz Begum.

On one October morning in that year, Noor Ayesha and her family members found their house surrounded by Myanmar soldiers. They put five of Noor Ayesha's children in one room, locked them in and set it on fire. All five were burnt to death. The military predators raped Noor Ayesha's two eldest daughters and killed them.

It was then her husband's turn to be killed and her turn to be raped. All these happened before her eyes. Five-year-old Dilnawaz Begum had hidden in a neighbour's house and survived. After losing eight family members and everything they owned, Noor Ayesha and Dilnawaz managed to flee to Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

The tribulation of Rajuma is another chapter in the long story of the sufferings of the Rohingya. On Oct 11, 2017, the New York Times reported that Myanmar soldiers invaded her village before forcing her and other women to stand in the chest-high waters of a nearby river.

The dark and threatening lust filled eyes of the soldiers were gazing at Rajuma. At their bidding, Rajuma waded to the bank while holding her baby son tightly. They hit her in the face, snatched her wailing son and threw him into a fire they lit to burn down Rohingya properties. They then gang-raped her.

Noor Ayesha and Rajuma did not go to Oxford University. Perhaps, it is likely that they don't even know it exists.

They don't hold talks or dine with prime ministers, presidents and other dignitaries. Nor do they have connections with powerful nations. However, if we look at their life through the prism of Thomas Gray's celebrated poem, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1750), we will not fail to acknowledge their human capacity and dignity.

They are not world-class celebrities. They also do not go to the International Court of Justice in The Hague to defend genocide offences. It is true that Suu Kyi won the election in a landslide. But we should not forget that a section of Myanmar's population — the Rohingya — was not allowed to cast their votes in this and previous "democratic" elections in Myanmar.

The disenfranchisement of the Rohingya does not seem to put to question the legitimacy and validity of democracy in the country.

When Noor Ayesha, Rajuma and hundreds of thousands of other Rohingya men and women were stripped of their citizenship, conditioned to live in poverty and humiliation, expelled from their homes and country and were subjected to ethnic cleansings and/or genocides, we did not see any protests or large demonstrations in Myanmar.

It was a primary responsibility of the people of Myanmar to stop the security services of their country from persecuting and annihilating a section of the population, their fellow countrymen.

Also, primarily,the onus was on the people of Myanmar to stop the monks from creating a climate of systematic exclusion and vulnerability, and from inciting violence against the Rohingya.

Unfortunately, the freedom and democracy-loving protesters who have taken to the streets demanding justice for Suu Kyi did not do so for the country's Noor Ayeshas and Rajumas, nor for millions of other Rohingyas who have been silently suffering inside and outside Myanmar.

They are impoverished, voiceless, defenceless and often invisible. Will today's protesters in the streets of Myanmar include the Rohingya in their struggle for democracy and justice?

Or, are they simply fighting for establishing selective justice? Selective justice is not merely incomplete justice; it is a travesty of the very notion of justice itself.

The writer is with the Department of English Language and Literature at International Islamic University Malaysia and can be reached at [email protected]