AN estate that was in existence for more than 150 years — home to hundreds of rubber tappers, field workers, estate management staff and the one-and-only dispensary health assistant — is gone.

Its closure not only ended the era of the rubber tappers but also took with it the unrewarded deeds of all who dwelt in it.

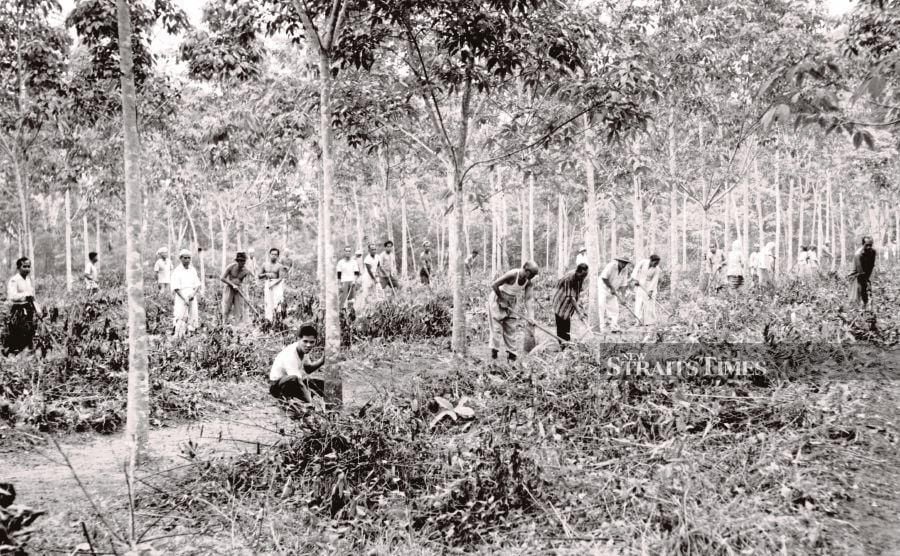

Bukit Jalil Estate (BJE) saw hundreds of families toiling for their daily rice and sambar.

Rain or shine, the weather was no hindrance to their tasks. Mountains, terrains, steep hills and slippery slopes were minor challenges. Many fell, only to return the next day with their shared thought — "I have to feed my family". This became every tapper's daily mantra. Serpents and wild boar met on the way did not deter them from bringing in the latex harvest to the store.

An estate labourer's layam, or home, had only two rooms partitioned with no doors — one as a bedroom and the other as a living room, dining room and study room, depending on the respective need. There was also a kitchen with a firewood stove and a bath without a tap. This is where my parents, siblings and I grew up as a family of 10.

We ate, studied, argued and played, mourned and laughed, and above all, had fun and love in this little abode. Our parents were diligent in ensuring we never felt pain or hunger.

As they were both out in the fields tapping every day, my eldest sister gave up her studies in middle school to take care of us and our home.

She tidied, washed and ironed our uniforms and clothes, bathed the younger siblings, including me, prepared all our meals, starting with breakfast at 5.30am. This was a common scene in many homes in the estate.

The estate dwellers were humble and decent. We rarely had any issues with gangsters or robberies. My four sisters were always safe and treated with respect and love by the estate folk. My brothers never once got involved in any major broils or fights, except the minor arguments bound to happen on the football field with the other youths.

Every member of BJE, regardless of age or gender, had respect and tolerance, care and love for one another, be it a family member or a neighbour or a friend.

Today, the estate is gone. The beautiful, tall flame of the forest has vanished. In place of tall mighty rubber trees, there are skyscrapers; the vast plantation is now a concrete jungle.

The rivers and streams, and eight narrow laterite roads are now covered or substituted with more than 1,000 roads intertwined among new houses and apartment buildings, golf courses and a stadium, hotels and shopping malls, several petrol stations, a technology park, an industrial estate and a leading private broadcast station.

All these new buildings and structures have phased out the many estate houses, the store and vulcanisation chambers. The Bukit Jalil Tamil School has been relocated. The only building standing in its original spot is the Bukit Jalil Mariamman Temple, where annual temple prayers are held in July.

With the demise of BJE, we also bade farewell to our trading friends — Oomayaan Uncle, Kacang Putih Uncle, Macam-macam Uncle, Ais Krim Potong Uncle, Manimaran Uncle, the uncle who polished our brassware, the uncle who fixed our millstone, and so many more who used to come by our estate.

The majority of estate workers have gone, and sadly, with unfulfilled hopes. All their lives they toiled and slogged day and night for a meagre income. The buzzing mosquitoes were their singers. The serpents were their watchdogs. The mandoors were their policemen. The rain was their income spoiler. They gave their best, and the estate flourished.

When modern development took over BJE, the estate community was cast aside. No empathy for their sorrows, no heart or compassion for their troubles. They were alienated, fractured, marginalised and powerless, and were expelled into semi and urban slums, with little or no compensation or government support.

After being evicted from their estate — the only place they knew as home — they stayed at the nearest squatters called Kampung Muhibbah, where the PPR flats are located.

While those sitting comfortably in their high chairs gained much wealth from the estate, the simple-minded workers wanted nothing in return except for a roof over their heads and recognition to cherish their long service.

Unfortunately, their hopes and dreams were never realised. After decades of service and giving their lives to the estate, their hard work was not duly rewarded.

"Freedom of rights" and "democracy for the rakyat" are phrases endlessly mentioned during election campaigns. However, once the votes are in, these calls go silent. The treatment of the estate workers is indicative of the exploitation of the weak and less fortunate.

Bukit Jalil's name is on several residential and other property addresses in the area. The estate may be no more, but the workers' desires and dreams still linger. There are about 30 families still residing in this hamlet among the development alongside a new graveyard, neatly placed right in front of my old estate house.

These are the folks who still hope that one day, the estate dwellers will be given decent houses for all their contributions in making Malaysia the foremost nation of Southeast Asia from the 70s to the 90s.

Anyone who is familiar may know how the name Bukit Jalil became synonymous in the area. I, along with thousands of Bukit Jalil Estate folks, am still waiting for the day when the estate workers are remembered.

As a mark of respect, a museum or memorial about the rubber estate community should be built to create awareness of the Indian community's efforts and contributions to Malaysia, during the formative years until today. History books and academics have overlooked them.

Many of us who had grown up in the estate are witnesses of the hard lives that we endured while living there. Moments of tears and joy, times of mourning and celebration, phases of worry and relief, points of disappointment and pride — these are memories that we can only cherish in our hearts and minds.

However, they are also crucial points in the lives of the estate community, and this is something that ought to be shared among Malaysians. There is much mention about the farming folk and industry among the Malays in Malaysia, the tin mining and trading with the Chinese folks in Malaysia, but there is little about rubber tapping by the Indian community in Malaysia.

In fact, rubber tapping was and still is a major contributor to the economy and industry today. Hence, it is only proper that the folks involved in this industry be given mention and saluted.

We can only pray the government would consider setting up a museum at the Bukit Jalil Estate site in recognition of every estate worker who had given blood and sweat to the estate, economy and country. The Bukit Jalil Estate has given everything to Malaysia. It's about time Malaysia gives back what has been long overdue.

This is the final instalment of Estate Chronicles