While salvaging the contents of a stately house that once belonged to Loh Cheng Hoe, a prominent Alor Star community leader, my endeavour uncovers a stack of flags that were initially hidden from sight by piles of clothes in the master bedroom wardrobe. Neatly folded and covered with protective plastic, they, together with many priceless historic keepsakes in the house, were obviously very much treasured by the previous owner.

Once unfurled, the priceless find turns out to be a near-complete collection of ensigns that were each flown in Kedah over a specific time period in the 20th century. While the British Union Jack, Chinese Kuomintang and Japanese Rising Sun flags were rather straightforward, the presence of a Siamese one proved rather baffling until memory recalls a period during World War 2 when Kedah, together with Kelantan, Terengganu and Perlis, were ceded by the Japanese Imperial Army to our northern neighbour as gesture of gratitude for aid extended during the early days of conflict in December 1941.

At the same time, a well-worn Federation of Malaya flag in the priceless hoard immediately brings to mind the hastily prepared and highly unpopular Malayan Union policy that added tumult to the already chaotic post-war period.

Bowing to pressure from the dominant Malay rulers and influential members of the Malayan Civil Service, the British quickly agreed to a new administrative system that eventually gave rise to the formation of Persekutuan Tanah Melayu two years later, on Feb 1, 1948.

FIRST UNIFICATION ATTEMPT

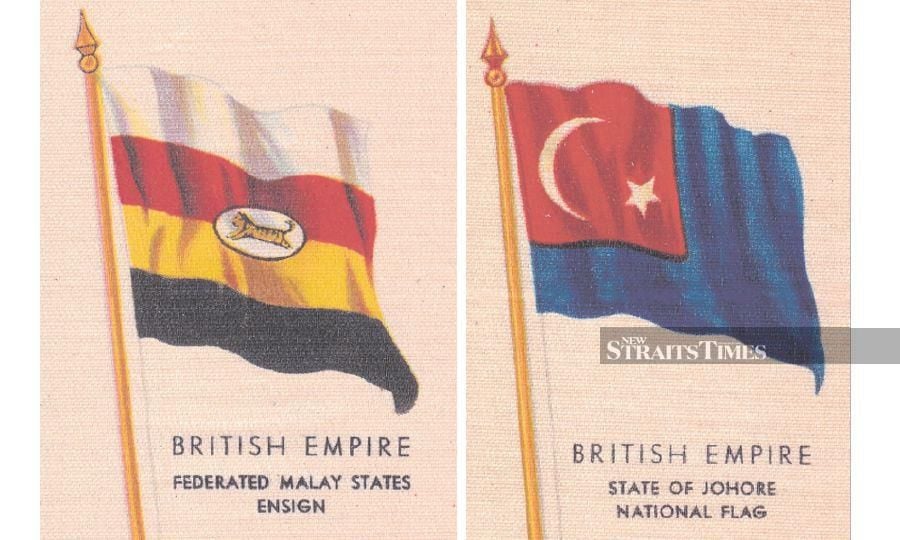

Apart from the short-lived Malayan Union, the Federation of Malaya was only the second major attempt in history for a unified Malaya Peninsula after the Federated Malay States, which came into existence following the union of Selangor, Pahang, Negri Sembilan and Perak on July 1, 1896.

Although more Malay states came under British influence in the early 20th century, they successfully resisted merger in a bid to retain some semblance of autonomy. It was only after the hardship and atrocities suffered during the Japanese Occupation that the idea of general unification began to gain widespread acceptance and prove attractive to the individual states.

Acutely aware that the flag, as a national symbol, was a potent source of political power and influence that was capable of rallying support by evoking emotional expressions of common identity, allegiance and self-sacrifice, administrators of the newly formed Federation of Malaya established a committee to set plans in motion for one that would unite all Malayans under a common cause.

PLAN FOR A NEW FLAG

The well-received idea led the Malay rulers to release a statement in March 1949 saying that they welcomed the plan for an official Federation of Malaya flag. Some five months following the royal nod of approval, members of the public were invited to submit designs that were deemed suitable.

Prerequisite, however, required those interested to keep representations simple by using not more than four colours. While the inclusion of recognisable national symbols like the keris, tiger and crescent were encouraged, participants were advised to adopt colours from the flags of the nine individual Malay states and two former Straits Settlement colonies that made up the federation.

In early November 1949, the Federation of Malaya chief secretary Sir Alec Newboult announced that a total of 370 designs were received and a report had been submitted to the Malay sultans for their views. Eager to seek public participation once again, the committee shortlisted three that were deemed most suitable and presented them to the people. Consequently, a public poll was held to determine the winning depiction.

The first two designs were rather similar in nature. They each comprised a blue background with two crossed red keris and 11 white five-pointed stars that were arranged differently in the middle. While the depicted colours of the duo were copied from those that made up the Union Jack, the equally spaced stars represented equality among the member Malayan states. At the same time, the keris, a weapon unique to the Malay archipelago, gave easy identification to Malaya.

WINNING DESIGN FROM JOHOR

However, it was the third design by Mohamed bin Hamzah that won by overwhelming majority when the final poll results were made known. Apart from six blue and five white horizontal stripes, it looked very much like the Johor state flag, which features a red canton containing a white crescent and five-pointed star that represented Islam as the official religion of the Federation.

My copy of the Malaysian Historical Society book titled Mohamed Hamzah: Perekacipta Jalur Gemilang: Bendera, Lambang & Lagu paints a compelling picture about the Johorean's eventful life story that eventually led to this landmark success.

Born at Kandang Kerbau Hospital, Singapore, on March 5, 1918, Mohamed grew up in Kampung Kubor near the Mahmoodiah Royal Mausoleum, Johor Baru. After completing education at Bukit Zahrah English School and Sultan Abu Bakar College, he secured a Johor government scholarship to pursue art at Raffles College in Singapore in 1936.

Returning to Johor Baru two years later, Mohamed began work as a Public Works Department draftsman drawing a monthly stipend of S$480. In 1939, his gift in art and exemplary work dedication helped secure the Sultan Ibrahim scholarship, which provided for participation in an advanced London-based art programme via distance learning.

World War 2 broke out soon after Mohamed received a Grade II Technical Assistant promotion. He took up arms by joining the Johor Volunteer Force Machine Gun Company in a bid to help defend his home state from the Japanese Imperial Army that was sweeping in from the north. Soon after the hostilities ended, the British decorated Mohamed with the Defence Medal in recognition of his gallantry.

MAKING THE FINAL CHANGES

Patriotism once again came to the fore when Mohamed came across the Federation flag design competition in the Straits Times on Aug 10, 1949. Creative juices flowed over the next three days while all else was put on the back burner.

The end results were four separate designs that met his demanding standards. When the results were announced several months later, Mohamed was over the moon as one of his designs was shortlisted and it subsequently garnered the most votes in the nationwide poll.

Unfortunately, his joy was short-lived as a decision was made by the Federal Legislative Council three days before Christmas 1949 to delay confirmation pending changes to the chosen design. Following constructive feedback from the then Johor menteri besar Dato Onn Jaafar and Kedah monarch Sultan Badlishah, the blue stripes were replaced with those in red, the red quarter was changed with one in blue, while the five-pointed star took on an additional six spurs.

Finally, nearly a year after the idea for a Federation flag was mooted, the final design with star and crescent in yellow received Legislative Council acceptance on April 20, 1950.

In his speech, acting chief secretary Moroboë Vincenzo Del Tufo reiterated the fact that the selection process had to be rigid as the flag was to become, more than any other national emblem, the focal point of loyalty and enthusiasm for all Malayans. At the same time, Sir Henry Gurney, in his capacity as high commissioner of Malaya, voiced satisfaction that the task of selecting the most enduring symbol of unity and national life had reached common consensus.

MALAYA HAS A NEW FLAG

The design surmounted its final hurdle after receiving the all-important green light from the Council of Malay Rulers and King George VI on May 19, 1950. Just five days later, the new Federation of Malaya flag fluttered for the first time at sea when the Malay sultans were entertained to lunch on board HMS Constance.

Made by renowned Kuala Lumpur departmental store Robinson & Co at a princely sum of S$50, the flag added colour to the otherwise drab grey C-class destroyer that was part of the 8th Royal Navy Squadron serving in the ongoing United Nations-led Korean War operations.

On May 26, 1950, Gurney, in the presence of the Malay rulers, officially hoisted the flag for the first time in a solemn ceremony — without accompanying music as our national anthem Negaraku was only composed some seven years later — on the dew-covered lawn of Istana Selangor in Kuala Lumpur.

Two visiting British cabinet ministers, the secretary of state for the colonies James Griffiths and the secretary of state for war John Strachey, together with federal and state councillors, were present when Gurney, in full colonial uniform and white gloves, proudly raised the flag 18 metres into the sky.

Apart from Robinson & Co, Kuala Lumpur firms C. J. Doshi and Gian Singh and Co also began taking orders after the Federal Legislative Council confirmed that flags used at official functions should adhere to the stipulated 1.8m by 0.9m (six feet by three feet) dimensions.

CHANGES MADE AS THE NATION GROWS

The manufacturers had pointed out that the lopsided canton width could be balanced by moving the lower margin up by just one stripe.

Council members, however, explained that the stripes represented the collective unity of all member states and signified hope that Singapore would join the Federation soon.

An additional white stripe at the bottom, they said, would bring the design components into perfect equilibrium.

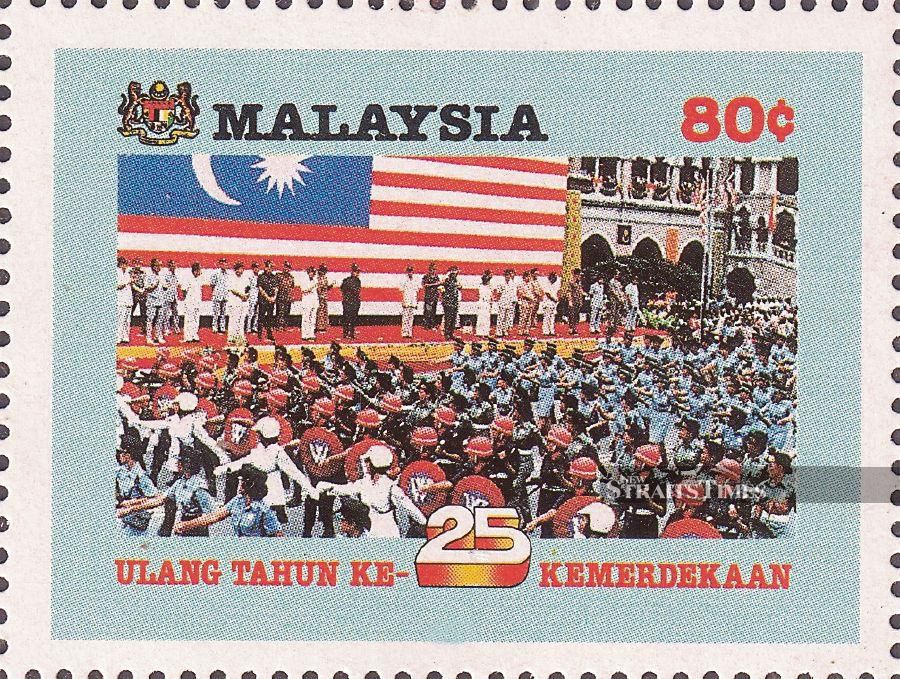

Perfect symmetry, in the form of additional stripes and spurs on the star, was achieved some 13 years later when Sarawak, Sabah and Singapore joined the Federation of Malaya to form an enlarged Malaysian collective on Sept 16, 1963.

Although the number of stripes and star spurs had to be reduced by one respectively following the expulsion of Singapore in 1965, the Malaysian flag reverted to its original state when Kuala Lumpur became a Federal Territory on Feb 1, 1974.

As Labuan (1984) and Putrajaya (2001) joined Kuala Lumpur as federal territories, the 14th stripe and point in the star eventually came to be associated with the federal government in general.

While remaining unchanged in terms of composition since then, our primary symbol of unity adopted the honorific name Jalur Gemilang following a competition that was open to members of the Malaysian public in 1997.

Aimed at spurring continuous growth and success, this glowing title has and will always evoke a stirring psychological state of solidarity that is shared by all who call this blessed land, home.