THE Orang Asli, especially those who live in rural settlements and in the forest, face numerous obstacles.

However, they are determined to improve their lives so that future generations can have a brighter future in modern-day Malaysia.

Many of them, who still practise a traditional way of life, have taken it upon themselves, albeit with a little help from good Samaritans and non-governmental organisations, to make sure they do not remain stagnant while the rest of the country surges ahead.

One such aspect involves education. Many members of the older generation are illiterate because they never had the chance to go to school, but they want to give the younger generation a chance of attaining a better life.

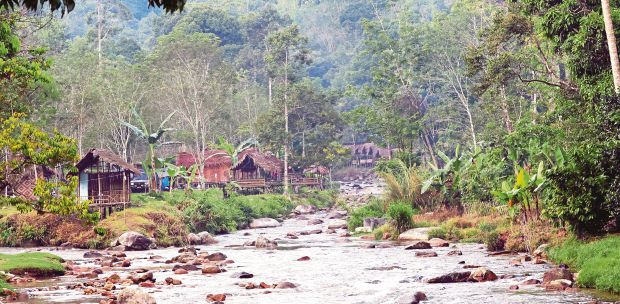

In rural places such as the Semai village of Ulu Ruai in Pahang and neighbouring Temiar villages of Ong Jangking and Kampung Sungai Laba off Gerik in Perak, the nearest schools are many kilometres away.

The journey through narrow, rough trails can be treacherous, depending on the weather.

The village chiefs or headmen, who are better known as Tok Batin, have made requests for schools to be set up in or near their villages.

But their attempts have yet to bear fruit.

So the villagers are now working with kind-hearted “outsiders” to ensure their children can get an education.

The Semai tribe in Ulu Ruai, for instance, obtained three vans with the help of the Rotary Club of Bukit Bintang and Persatuan Komuniti Kasih Selangor (PKKS).

This allowed children from the villages to go to the nearest schools — Sekolah Kebangsaan Pos Cenderot, which is 25km away, and a secondary school in Sungai Koyan.

“Education is vital because the future generation might not want to live the traditional way of life here in the forest.

“They can be better prepared for life in urban areas and get jobs if they decide to be adventurous and move out,” says Pastor Yakhem, 56, a Semai elder who has 14 children, 28 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren from two marriages.

However, not all parents are happy to send their children to schools far away, and many of the children drop out of school for various reasons.

With the help of the same two organisations, classrooms and learning centres along with libraries were built in two of the villages so that all the children could receive a basic primary education.

Volunteers from Kuala Lumpur take turns to teach the children once a week, and are ably aided by determined Orang Asli youths who are training to be teachers themselves.

One volunteer is semi-retired condominium manager Catherine Che Loo Peng, 56, who started teaching English in Ulu Ruai four to five years ago. She wanted to help the Orang Asli, while also addressing the problem of children dropping out of school.

“At first, I taught only English, but then I realised that it was not sufficient and I began to help to teach the children other subjects such as Mathematics.

“Some of the parents were sceptical about enrolling their children in school and the attendance was not encouraging.

“This was because many of the children had to help their parents in all sorts of ways, such as hunting for food, doing household chores and tapping rubber or tending to the plants and vegetables which they cultivate to feed themselves.

“The Orang Asli are a close-knit community, they do almost everything together. So we take turns to teach once a week so that the children can gain an education.

“Thankfully, things have changed. Many parents are sending their children to our classes or to schools, as they are slowly but surely realising that while they stick to their age-old traditions, the world around them is evolving. They realise that gaining an education can help to change their lives for the better,” says Che.

Gina Ahmad, 28, a Semai from Ulu Ruai, has stepped up to do her bit by becoming a teaching assistant.

“I decided to become a teaching assistant because I like teaching and I get to be close to the children and impart knowledge to them, which will make their lives better.

“One of the students is my own son who is 9 years old,” says Gina, who helps to teach Bahasa Malaysia, English and Mathematics, and who aspires to be a fully-fledged teacher.

Another aspect that the Orang Asli are keen to improve is their livelihood and the means of sustaining themselves.

“In the old days when I was a child, we were nomadic and used to move around a lot. We were hunter-gatherers and foragers, living off what we could get from the forest, hunting wild animals like wild boar and picking fruits, and we managed to survive.

“But now we no longer move around. We have stayed put here in this village for years, and living off what we can get from the forest just isn’t enough. We knew that we needed to find ways to diversify our income to sustain our entire village,” says Yakhem.

“Initially, we began tapping rubber and selling what we got from the forest like durians, petai and Tongkat Ali roots to outsiders in nearby towns. But it just wasn’t enough, as we’ve got a community of around 400 villagers, with close to 100 children to feed and nurture as well.

“Thanks to PKKS, we now rear livestock like chickens and ducks. We began this a couple of months ago, and it not only feeds the entire village but is a valuable source of income as well.”

However, in the remote village of Ong Jangking off Gerik in Perak, the Temiar tribe still practises a traditional way of life as hunter-gatherers and foragers. They rely mostly on what they can get from the forest to sustain themselves.

Village committee member, Anjang, 30, says they are able to sustain themselves till this day without the need to venture into rearing livestock or farming.

“We have not relied on other ways to support ourselves as we are able to survive by living off the land just as our ancestors had done. So we still hunt for animals such as wild boar, snakes, and even monkeys using blow pipes, as we can eat just about anything (laughs).

“Even though in the outside world, especially in the nearest town of Gerik, we can see there’s a lot of development going on, we are getting along just fine.”

Anjang also points out that despite living in a remote area of the forest and with the nearest school kilometres away, they are not deterred from giving their children an education.

“As parents, we make sure our children go to school and get an education, be it in the community classrooms at the neighbouring village of Kampung Sungai Laba, or even if it means they have to live in a hostel and return to the village only during school holidays.

“And mind you, my elder brother Ramli, 32, and I did exactly that when we were young.

“Both of us managed to finish our schooling, spending our primary and secondary school life in a hostel.

“Even though we wanted to stay back in the village to help our parents, they were adamant that we should go out to receive an education so that not only would we be able to think for ourselves, but we would also play a part in leading our community and village in the right direction, which we are trying to do right now,” says Anjang proudly.

With such willingness and determination to learn so that they can better equip and sustain themselves in the ever-changing Malaysian landscape, the future does not look all too bleak for the Orang Asli.

They will be able to move ahead albeit at a slower pace, while still holding on to their rich heritage, culture and beliefs.