KUALA LUMPUR: News of the untimely death of Iman, Malaysia’s last-known surviving Sumatran rhinoceros, was heart-wrenching. The incident has far-reaching effects on our nation’s rich biodiversity as the species Iman belongs to is virtually extinct within our borders.

The 25-year-old rhinoceros, belonging to the Bornean or Eastern Sumatran subspecies, succumbed to uterine tumour even though she was given the best care and medical attention.

Despite this major setback, the Sabah Wildlife Department harbours hope of reviving the species by working with its Indonesian counterpart to artificially inseminate Iman’s harvested ova using in vitro fertilisation.

The smallest of the rhino family, the Sumatran rhinoceros is the only one that has two horns.

This highly endangered species once roamed across Asia as far as India.

But today, experts from the World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that there are only fewer than 100 members of this species left, with the majority found in Sumatra and Borneo.

BORNEAN RHINOCEROS: FACT OR MYTH?

It was not until 1839 that the scientific world was alerted to the fact that rhinoceroses existed in Borneo.

Although not everyone was ready to accept the fact when it was first made known, a lively discussion was started to debate the slim possibility and, if proven true, subsequently determine its identity.

The reason for their postulation stemmed from the fact that only two rhinoceros species were known in Southeast Asia at that time: the one-horned Javan rhinoceros and the two-horned Sumatran rhinoceros. As the probability of the existence of a third species was debunked by the majority, most experts at that time trained their thoughts on guessing which of the two existing species were roaming the jungles of Borneo.

Much speculation, wrong identification and controversy ensued and it was not until some 45 years later that an answer began to surface. The route to identification that experts took closely resembled something worthy of the plot of an exciting mystery novel.

In 1839, a skull was sent to the Natural History Museum in Brussels by the great naturalist and collector A.H. von Henrici, who claimed it came from Borneo. Unfortunately, this initial specimen failed to spark any interest and was overlooked by 19th-century scientific literature.

The world had to wait a year later for renowned German naturalist Salomon Muller to provide reasonable proof. His account, which was substantiated by Malays and Dayaks he met, included a sighting in the upper region of Kahayan river, the largest tributary in central Kalimantan.

While describing that the male rhinoceros was equal in size to a large buffalo, Muller erroneously reported that it was only armed with a solitary horn. Later scientists postulated that he must have seen a Sumatran rhinoceros with a poorly developed posterior horn, something that was considered unimportant to note back in the 19th century.

CONTRADICTING EVIDENCE

Silence reigned for some time after Muller’s account was published as very few people dared to touch this vexing question. Nevertheless, hushed whispers within the scientific community revealed that many doubted the idea, while those who accepted the hypothesis conceded that the species’ identity was extremely difficult to determine.

People on the extreme end of the scale based their argument on contradicting evidence that arrived in Europe and said such an animal did not exist at all. An incident at the British Museum in London in the early 1860s gave them more reason to support their cause.

Keen to participate in the debate and provide a crowd-drawing exhibit, museum curators acquired a rhinoceros skull from a dealer who asserted with great conviction that it came from Borneo. After consulting with experts and making detailed comparisons to existing specimens, the claim was refuted and it was declared that the skull was from Java and not Borneo.

In 1869, the existence of the Bornean rhinoceros was put beyond doubt when William Fraser wrote a letter in response to a query from the Zoological Society of London. Writing from Surabaya, he attested that the crew of a ship plying between Java and Borneo had seen the animal and that it lived in the interior.

The 1870s saw more and more material of the two-horned species arriving in Europe. Coupled with several rhinoceros specimens sent to European museums from Borneo and a detailed report on material in the Kuching museum, which consisted of four heads and three horns, the mysterious animal was close to being identified with certainty.

LIVE RHINOCEROS IN 19TH-CENTURY EUROPE

Opportunity arrived in 1896, when the Zoological Gardens of Amsterdam bought a young female Sumatran rhinoceros from H. Owen, a wildlife collector for 2,400 guilders. It arrived at the start of summer on the cargo ship SS Telemachus and became an instant crowd-puller apart from drawing intense interest from the European scientific community.

The animal, already weakened by its long sea voyage and suffering from a lack of proper diet, lived for just six months in the zoo before succumbing to the harsh European winter and other complications on Dec 16, 1896.

It took another four decades before knowledge on the Bornean rhinoceros received further significant expansion and recognition as a subspecies of the Sumatran rhinoceros.

Tom Harrisson, a British polymath, arrived in Borneo for the very first time with the Oxford University expedition team in 1936. He returned again at the end of World War 2 in 1945, where he and three other British parachutists landed in Bario in the Fifth Division and later in Pasir Nai in Sarawak’s Third Division to liberate Sarawak from the Japanese.

When Sarawak was ceded by its third rajah, Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, to Great Britain in 1947, Harrisson was offered the post of government ethnologist and Sarawak Museum curator, a job that he held for twenty years until his retirement in 1966.

IMPORTANT DEFINITIVE WORK

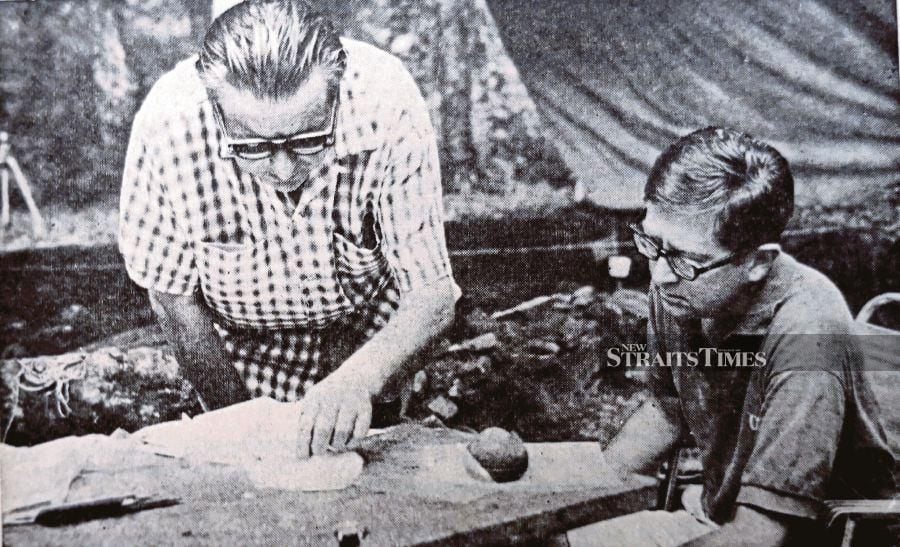

During the duration, Harrisson embarked on many expeditions in Borneo and tried to assess the status of the Bornean rhinoceros by talking to locals and through personal observation.

In 1956, he wrote an extensive paper on the local rhinoceros in the Sarawak Museum Journal that incorporated older accounts, as well as his personal discoveries. While that publication has remained the single most important definitive work on the subject, Harrisson did not rest on his laurels and continued to put pen to paper whenever new discoveries came to light.

During the course of his studies, Harrisson became aware of the precarious situation facing the Sumatran rhinoceros. In his opinion, the low population size spread over vast areas of dense jungle put the animal in grave danger of becoming extinct.

He was adamant in making the world sit up and take notice that he, together with Hugh Gibb, produced a six-part series that highlighted the people and animals, including the Bornean rhinoceros, in Sarawak. The Borneo Story was broadcast by BBC in 1957.

His tireless crusade to help the animal he loved most did not go unnoticed. The scientific community acknowledged his efforts by immortalising his name in the nomenclature of the Bornean subspecies of the Sumatran rhinoceros, calling it Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni.

UNDERSTANDING SARAWAK’S RICH HERITAGE

During his tenure as museum curator, Harrisson, who was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1959, was also interested in archaeological work and invested a lot of time getting to know the Malays, Ibans, Kayans, Punans and Baketans to further his understanding of Sarawak’s rich cultural heritage.

Harrisson’s largest and probably most important archaeological project in Borneo was the Niah Caves initiative. Covering over two decades and involving hundreds of thousands of dollars, the study was of the same order of magnitude as many of the world’s largest excavations at that time that focused on advancing knowledge on all things prehistoric.

Although he was not professionally trained in this area of study, Harrisson applied many of his sound ideas and achieved results worthy of a first-class archaeologist.

The first pictures of the Great Niah Cave appeared in a 1956 scientific paper that Harrisson jointly published with George Jamah in the Sarawak Museum Journal. His most important discovery in that gigantic cavern was a human skull dated by radiocarbon to be 40,000 years old and widely considered as the earliest date for modern human existence in Borneo.

Financing the digs posed a major headache for Harrisson as Niah was far from urban and transportation centres. Colonial budget at that time for Sarawak was not large and, in setting priorities, development, health and education normally received the lion’s share of the funds.

As a result, the first major funding for the Niah Caves research did not come from government coffers. Harrisson, through his personal friendship with influential executives in the Shell Oil Company, was able to secure initial funds and continued assistance not only in terms of financial support, but also loan of expensive equipment, like helicopters, which he used to great advantage during survey work.

On a smaller but equally important scale, he received grants from the Portuguese Gulbenkian Foundation and wealthy businessmen in Sarawak and Singapore. While feeling grateful, Harrisson knew that all the support that he had received would not have been possible without his famous Mr Sarawak image and the worldwide publicity given to the Niah Caves through television broadcasts.

QUELLING A REVOLT

Towards the end of his tenure in Sarawak, Harrisson’s experience in the military was once again called to the fore when the Brunei Revolt broke out in 1962. Resident John Fisher in the Fourth Division sought the help of Dayak tribes by sending a boat up Baram River with the traditional Red Feather of War.

At the same time, Harrisson renewed ties, forged during his guerrilla campaign against the Japanese towards the end of World War 2, with his Kelabit friends from the Bario Highlands in the Fifth Division. Hundreds of Dayaks responded to the clarion call and formed companies led by British civilians commanded by Harrisson.

The force, which was some 2,000 strong, had excellent knowledge of the tracks through the dense jungle. Moving quickly, the men played a major role in containing the rebels and cut off their escape route to Indonesia-controlled Kalimantan.

After tensions had subsided, a lighter take of his deep affection for the people of Sarawak was seen when World Health Organisation officials sprayed Kelabit longhouses to eradicate mosquitoes that caused malaria. Their action unintentionally killed other insects, like cockroaches.

Harrisson was very disturbed after hearing that there was a proliferation of rats in the longhouses as all the cats had died after consuming the poisoned cockroaches.

He set his men to work by rounding up every available stray cat from Kuching to the coast and dropped them by parachutes in containers on Kelabit villages.

Upon his retirement, Harrisson travelled the world and lived in the United States, the United Kingdom and France. Both he and his wife died in Thailand when the bus they were in collided with a timber truck on Jan 16, 1976.

Although losing Iman is a great loss for Malaysia and the world as a whole, the work of Harrisson and his fellow researchers will not be in vain as certain quarters in the scientific world are harbouring hope that remote places in Sabah, like the Maliau Basin Conservation Area in the heart of Borneo, might reveal the presence of undiscovered Bornean rhinoceros populations.

If, by a long shot, the second chance is bestowed upon us, we must take all necessary steps to prevent history from repeating itself again.