The news item concerning a murder that shocked the people of faraway Iceland must have escaped my eyes if indeed it was published in any of the country’s news publications.

But if it was, I hasten to apologise for repeating what I came across on BBC World last Friday.

Iceland is united in grief, the news report began. The body of a 20-year-old woman, Birna Brjansdottir, was found washed up on a desolate, cold beach last weekend after being reported missing more than a week before.

Such murder cases are rare in a country with one of the world’s lowest crime rates.

This is not about a murder per se, but rather about the homicide rate in a tranquil country that rarely sees threats against a person. And why can’t we be the same?

Over the last two decades, an average of about two people have been murdered annually in the small and prosperous nation. It has had entire years — 2003, 2006 and 2008 — when not a single person was murdered.

But Iceland, where police officers do not carry firearms, has been shaken by the death of Brjansdottir, a fun-loving, sales assistant who worked at a department store in a shopping mall. Her disappearance more than a week ago, after last being seen staggering down a street in downtown Reykjavik, prompted the largest search-and-rescue operation in decades.

Unlike Iceland, Malaysia has a high crime rate. Murder is committed practically every day. We have heard of a drug junkie even murdering his own mother when his daily fix was denied.

There have also been stories of murder being a consequence of jealousy, a result of conspiracies and of gangland clashes. We also come across physical violence from bullying, which sometimes ends in death.

Perhaps compared with Iceland, it is the culture here where people lose their heads that easily; perhaps it’s the hot weather here that makes them do crazy things. But there must be an explanation even though the population of Iceland is about 100 times less than Malaysia.

On Sunday, Jan 22, Brjansdottir’s body was found near a lighthouse on the Reykjanes peninsula, more than 40km from where she disappeared. The post-mortem examination was clear — she had been murdered.

Icelanders responded by putting a candle in their windows. Social media was flooded with messages for Brjansdottir. People broke down in tears. Flowers were placed on the spot where she disappeared. People in neighbouring Greenland were also shocked. Crowds gathered with candles in six different towns and also placed candles in their windows.

Such was the display of emotion in a laid-back and untroubled land.

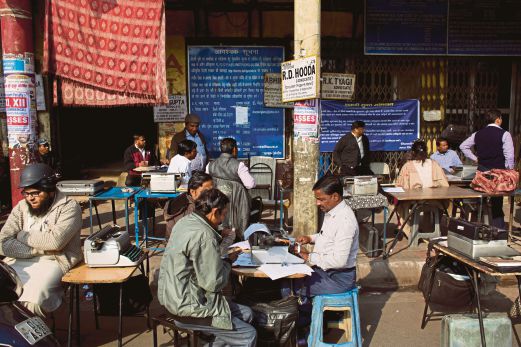

On a similar note, in India, the typewriter still cannot die, though it may have reached the end of its lifespan. Unlike other places where the typewriter, at best, has been reduced to the display rack, India is fighting hard to function with that trustworthy processor that has served so well over the years.

An Associated Press item last week noted: “Looking around the cramped classrooms, you might think that the typewriter still has a future in India. But in one of the last places in the world where it remains a part of everyday life, twilight is at hand.”

The story quoted Sunil Chawla, whose father founded the family company selling typewriters nearly 60 years ago, but whose own sons chose to avoid the typewriter business: “I’ll keep it alive as long as possible. But after me, I don’t know what’s going to happen. There’s no future in this business.”

For now, only one thing keeps him in the business: “I’m a typewriter man,” he said. “I still have a soft spot for them, and I don’t want to let it go.”

In India, the typewriter was never just a piece of office equipment, AP said. It was a sign of education, of professional achievement, of women’s growing independence as they slowly entered the workforce. It’s been a Bollywood plot line and a symbol of nationalism.

Syed Nadzri is former NST group

editor